Shin Pain

Running, hiking, playing sports and exercising can all cause shin pain.

Pain in the shin, or lower leg, can present in a variety of ways, and for a variety of reasons. Each of these causes requires a different type of treatment, and not all shin pain is the same! Therefore, it’s important to have your shin pain evaluated by a physical therapist in order to provide you with the ultimate treatment to match your diagnosis! Let’s start by looking at the different types of shin pain and the potential causes and treatments for each.

Let’s look at some common causes and treatment options for each:

1.) Tibial Stress Syndrome (“Shin Splints”) & Stress Fracture

2.) Chronic Exertional Compartment Syndrome

3.) Posterior Tibial Tendon Dysfunction

Tibial stress syndrome and Stress Fractures

What is it?

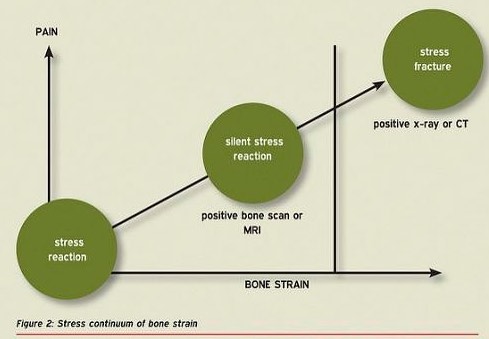

Perhaps you’ve heard of the term “Shin Splints”. Perhaps you’ve experienced this pain yourself while running or hiking. Most people think of shin splints as a minor injury, but if you ignore this pain, and continue to exercise through the discomfort, it could lead to a “stress reaction” or stress fracture!

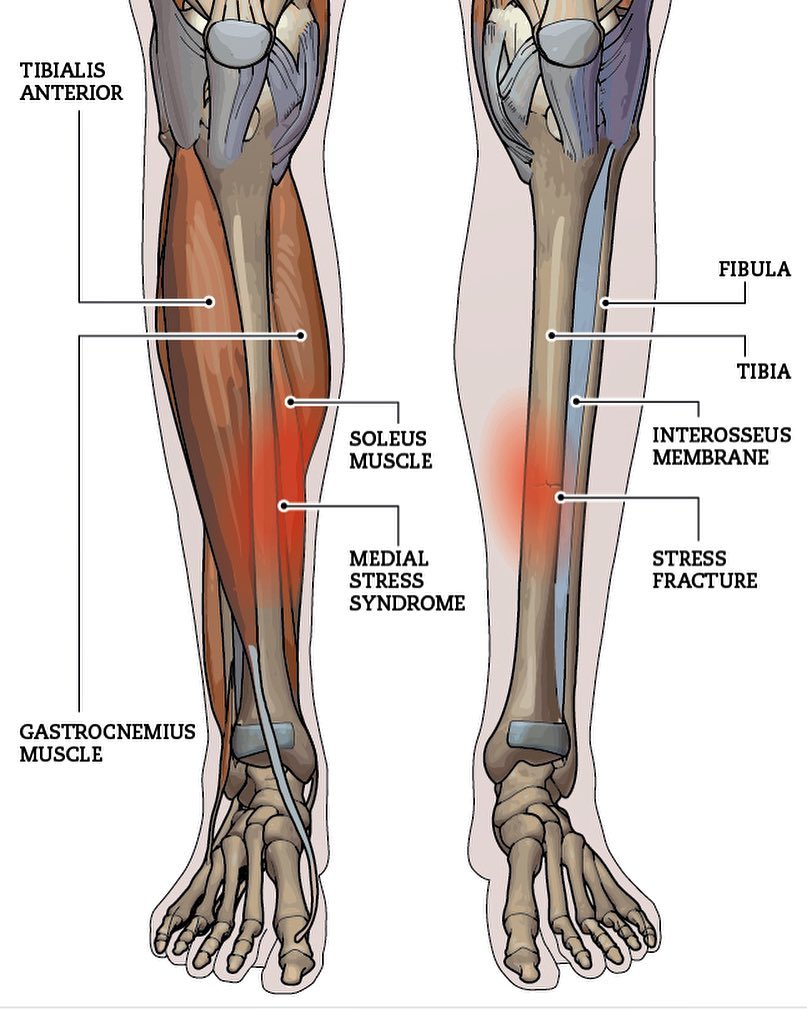

“Shin Splints” is a commonly used term for Tibial Stress Syndrome (TSS). TSS is an overuse or repetitive stress injury that most commonly affects the inside (or medial) part of the lower leg bone, the “tibia”. As a result, this injury is often called Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome or MTSS. Repetitive activities, such as running and playing sports, can cause repetitive muscle loading and boney impact forces along the shin bone, eventually leading to pain. Imagine this…if you sit there and poke yourself in the leg 20 times, it probably doesn’t hurt. But, if you sit there and poke your leg a thousand times in a row, in the same spot, it will eventually hurt. That’s what happens with tibial stress syndrome. The muscles that attach onto your tibia are very important stabilizers of the foot and ankle during activities like running and playing sports. When they’re used over and over and over again, the repetitive strain to these muscles and their bony attachments can cause stress to the bone. In cases of heavy use and/or inadequate recovery, it is possible that this ‘syndrome’ can lead to a stress reaction or stress fracture…more to come on that soon.

MTSS accounts for approximately 10-15% of running injuries and as much as 60% of all lower leg pain in active people!1 (For more on running related injuries, click here.) Some research suggests that up to 35% of athletes who run and jump experience tibial stress syndrome at some point in their athletic careers.2 So, with those statistics in mind, there’s a good chance that you have experienced this pain yourself or know someone who has.

What does it feel like?

‘Shin splints’ are most commonly felt along the inside part of the tibia (shin bone), but pain can be felt along any location of the tibia. This injury is typically worse with activity and improves with rest. Most patients will report an aching type of pain during activity but a sharp tenderness to palpation over the injured area. In the early stages, it may take more activity to cause symptoms, and symptoms typically recover quickly once the activity is stopped. In later stages, the pain can come on early during activity and take a lot longer to recover.

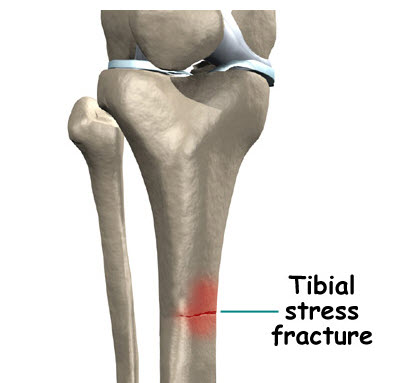

A stress reaction may not sound like a big deal, but if ignored it can lead to a stress fracture, and this is a big deal. Stress reactions can be thought of as the middle ground between tibial stress syndrome and a stress fracture. Essentially when a stress syndrome progresses to a stress reaction, there is weakening of the superficial layers of the bone. When a stress reaction progresses to a stress fracture, there is physical fracturing or a tiny “break” in the bone. Most times, it can be difficult to know what stage (stress syndrome, stress reaction, or stress fracture) your injury is in, so it’s important to consult with a physical therapist for a comprehensive evaluation. To schedule with a sports physical therapist at VASTA, click here!

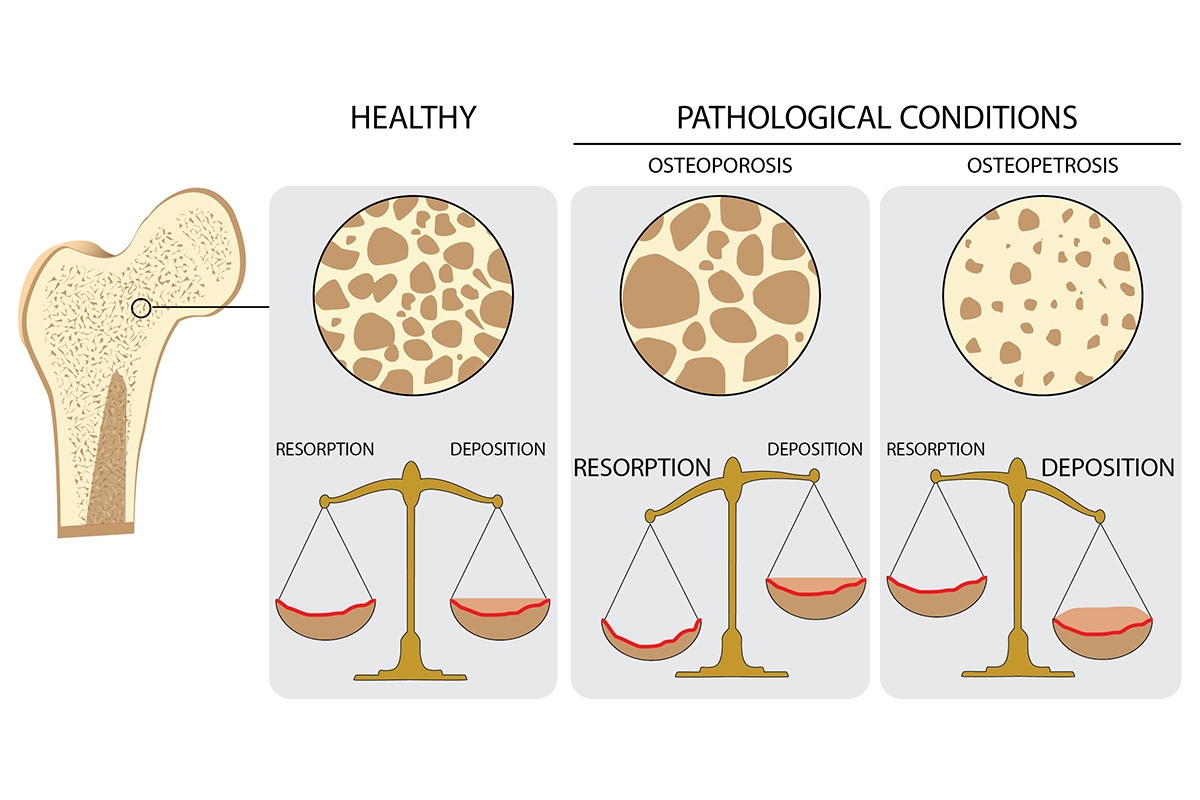

Stress fractures essentially signal that the body’s ability to lay down new bone can’t keep up with the demands that you, the athlete, are placing on the bone. When you perform weight bearing activities, bones are exposed to certain amount of ‘load.’ The body then signals cells in the bone to remodel the bone and make it stronger. However, when the training demands are so great that the body can’t keep up, the bone cannot remodel and become stronger, and it breaks down slowly over time.

Shin splints and stress fractures can be caused by a wide variety of factors, but here are a few of the big ones:

- Prior history of stress fractures or MTSS

- Elevated body mass index (BMI)

- Training errors – ramping up volume and/or intensity too quickly, inadequate recovery strategies, overtraining, etc. (Scroll to the middle of the ‘Running Related Injuries’ article for more on common training errors and how to prevent them!)

- Improper biomechanics in the running form – To have your form evaluated, see a physical therapist at VASTA for a comprehensive and detailed running analysis

- Improper footwear

- Poor nutrition

- Females are more likely to experience MTSS. See The Female Athlete Triad to understand why that may be true.

What do I do if I think I have MTSS or a Stress Fracture?

Treatment for MTSS and a stress fracture are much different, so it’s important that your treatment matches your diagnosis. To make things simple, a stress fracture requires that you cease all painful activities. PERIOD. That means, no running, no sports, etc. if these activities are causing pain. Therefore, it’s very important to consult with a medical professional, such as a physical therapist, to ensure that a stress reaction does not progress to a stress fracture.

Managing MTSS is all about determining the cause of the pain. If training errors are a big culprit, your physical therapist will work with you on developing a training program that focuses on allowing for recovery while keeping you active. If there are biomechanical factors associated with your condition, your PT will work with you on solving these factors. Some examples of contributing impairments include:

If you suspect that you have MTSS, there’s some easy things you can start with right away!

- Ice to the injured area after activity for 15-20 minutes

- Calf foam rolling and stretching

- Massage to the surrounding calf and foot and ankle musculature – To schedule a massage with VASTA’s licensed massage therapist click here!

Do I need an x-ray or MRI?

Maybe! It is certainly possible that an x-ray or an MRI is warranted whenever a bone injury is in play. In the vast majority of cases, however, MTSS can be diagnosed via a patient history and a clinical exam.14 However, if your physical therapist suspects that you have a stress fracture, imaging is certainly warranted in order to rule out this injury. X-rays are typically very reliable for detecting larger fractures, but stress fractures can easily be missed! In fact, x-rays taken 2-4 weeks after the onset of the injury are usually negative.15 The take home here is that even if you have an x-ray and it is negative, it doesn’t necessarily mean you don’t have a stress fracture. An MRI is the most specific and sensitive for ruling out a stress fracture.16

Do orthotics help?

Orthotics can be an effective option to help improve foot and ankle alignment. If you are someone with “flat feet” an orthotic that provides some arch support can help to reduce repetitive stress to the medial column of the lower leg. While this sounds great in theory, a lot of the support for the use of orthotics is largely anectodal, meaning there isn’t strong research to support their use for these conditions.

The causes of MTSS are many, and therefore, one specific intervention is unlikely to solve all cases (or even most cases). Each athlete must be considered individually. For this reason, the evidence for the effectiveness of orthotics in treating MTSS is equivocal, although there may be some indication that, when combined with flexibility exercises, orthotics can be helpful.17 Bottom line – orthotics may be one part of an appropriate comprehensive treatment plan for you… or not! A sports physical therapist specializing in lower extremity biomechanics can evaluate your foot/ankle alignment and your gait to determine whether orthotics are indicated.

Chronic Exertional Compartment Syndrome

What is it?

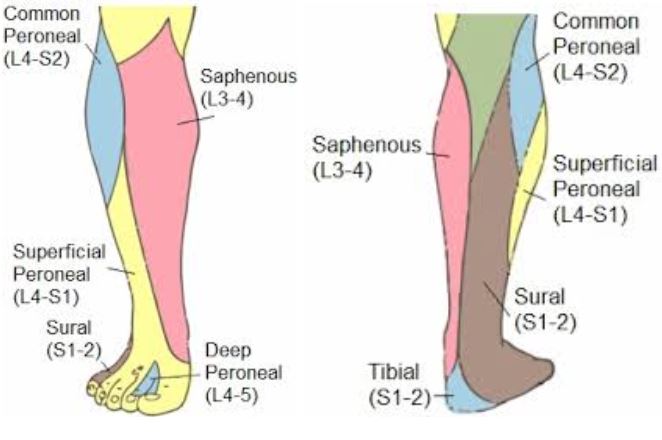

Chronic Exertional Compartment Syndrome (CECS) is another cause of lower leg and shin pain that is difficult to discuss without understanding the anatomy of the lower leg, so let’s start there first. The lower leg (from the knee to the ankle) is separated into different ‘compartments’ with each compartment contained a group of muscles, nerves, and blood vessels. The reason they are called compartments is because the front, the lateral side, and the back of your lower leg each have a layer of connective tissue, known as fascia, that separate the groups of muscles.

The front, or anterior compartment, of the lower leg contains the muscles that are responsible for flexing your toes towards your knee and slowly controlling your foot down towards the ground when running or walking. The lateral compartment contains muscles that are responsible for controlling the motion of the foot inwards and outwards, and the back, or posterior compartment contains your calf muscles and the muscles that flex, or curl your toes. Up to 95% of cases of CECS occur in the anterior and lateral compartments of the lower leg.18

The reason this condition is called chronic ‘exertional’ compartment syndrome is because of the fact that the symptoms associated with this condition are activity based. Often, the pain associated with CECS builds over time and typically, there is a 22-month delay in the diagnosis of the condition, so this is not an acute injury.19 In general, symptoms are only aggravated by exercising with your legs, when you are “exerting” yourself, such as when participating in distance running or sporting activities. Muscle volume can increase up to 20% of its resting size during exercise.20 This increased muscular volume causes an increase in intramuscular pressure, which impedes local muscle blood flow, thereby impairing neuromuscular function of tissues within the specific compartment. Each compartment only has a finite amount of space available to it because of the fact that the fascia in between each muscle is inflexible. When the muscles of the lower leg are repeatedly worked and the muscle volume increases, the space of each compartment is reduced, and the pressure inside increases.

What does it feel like?

The most common symptoms that help to differentiate exertional compartment syndrome from a stress reaction or fracture, is a sense of nerve like symptoms.21 These symptoms can range from numbness to tingling to “burning” in the foot and ankle, with the location of these symptoms being largely dependent on which ‘compartment’ is involved. Based off the location of where you feel these symptoms, your physical therapist can help to diagnose the location of where the compartment syndrome may be taking place. Important note – tingling or numbness with exercise does not mean you have compartment syndrome! There are many, many reasons you may be feeling this sensation, so it’s important to have this evaluated in much greater detail.

So, if nerve like symptoms aren’t the only symptom, what else might you feel? Patients dealing with CECS, often report pain and “tightness” in their lower leg while exercising. This is probably because during progressive muscle activity, rising intracompartmental pressures cause impaired muscle tissue perfusion, or blood flow. This lack of blood flow creates an environment in the muscle where it is deprived of sufficient oxygen, leading to a sensation of ‘cramping’, pain, or ‘tightness’. Ever done a heavy set of squats and taken your muscles to complete failure? This sensation of fatigue and “feeling the burn” is comparable to what is happening with your muscles in CECS, but it’s at a much, much higher intensity. Patients also typically describe pain with stretching the muscles of your lower leg.

Risk Factors for Developing CECS22 23

- Recreational and elite distance runners

- Athletes who participate in ball and puck sports

- Most commonly affects those between 20 and 40 years of age

- Anabolic steroid and creatine use, which increases muscle volume

- Abnormal running form, causing over-reliance on one compartment of the lower leg

Do I need surgery?

Surgery may be indicated for compartment syndrome, but it is recommend to attempt rehab prior to undergoing surgery for CECS. If CECS is suspected and the combination of physical therapy and activity modification is unsuccessful at reducing symptoms, the doctor will do a test known as the “compartment pressure measurement.” During the test, the pressure in the involved compartment is measured before, during, and after exercise, by inserting a needle with a pressure gauge. If compartment syndrome is diagnosed, the doctor may decide a procedure is necessary. The procedure performed is known as a ‘fasciotomy’ in which the doctor surgically releases the fascia that separates the compartments of the lower leg with the goal of reducing the increased pressure in the lower leg. A patient undergoing a fasciotomy will have to spend a period of time in the hospital to ensure that the pressure normalizes and the wound heals properly. Following a fasciotomy, physical therapy is used to restore the range of motion, strength, and function of the leg.24 Typically, this fasciotomy procedure is successful as research indicates that recurrence rates following this technique range from 3-17%.25

How does physical therapy help CECS?

The primary goal of the initial phase of physical therapy is to reduce training activity and/or intensity in order to reduce repetitive strain to the involved muscles of the lower leg. Your physical therapist will work with you in order to determine how to appropriately manage your activity levels, as allowing for recovery is of utmost importance with CECS. Once pain levels are well controlled, PT is going to focus primarily on preventing this ‘injury’ from coming back again in the future. It’s possible that there could be other factors contributing to CECS, including weaknesses in other areas of your body that could be leading to overuse of the lower leg musculature.

Because the treatment for CECS is so patient specific, there is no ‘gold standard’ for PT interventions. However, a case study done by Collins and Gilden,26 demonstrates how “proper” treatment should target the entire lower extremity, highlighting the treatment of a 34 year old triathlete with compartment syndrome in the lower leg. These therapists used soft tissue massage and joint mobilizations to the foot and ankle as well core and hip strengthening in order to treat their patient. They also utilized a hip stretching routine in order to address limited mobility in the athlete’s hips. They proposed that limited mobility and weakness of the joints above the injury may have contributed to the CECS of the lower leg. The patient was treated for 3.5 months and checked back in with the PTs 4 months after completing their rehab. The athlete was able to return to training and did not have his symptoms return at that 4 month check in visit.

Posterior Tibial Tendon Dysfunction

What is it?

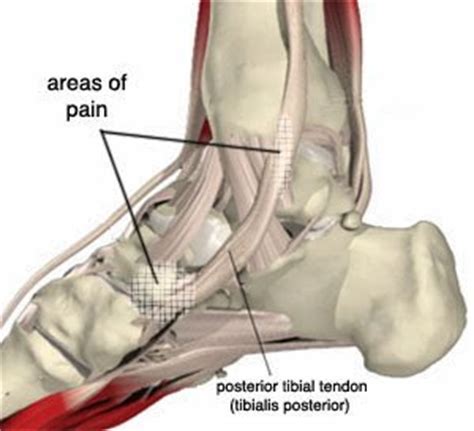

The tibialis posterior muscle is a long, thin muscle that attaches to the back surface of the lower leg bones (the tibia and fibula). This muscle runs along the back and inside of your shin. It’s tendon runs along the inside of your ankle, just behind the boney bump (called a Malleoli) and then attaches under the mid-foot to many of the bones that make up the arch. Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction, or PTTD, is a disorder of the lower leg, ankle, and foot that can result in a progressive loss of the arch of the foot. This condition is relatively common, as it affects nearly 5 million people in the United States alone.27 With varying degrees of severity, the symptoms associated with this disorder can range from pain along the inside of the ankle during initial stages to a loss of joint mobility in the foot to a rigid and arthritic foot deformity later in the disease process.28

What does it feel like?

The signs and symptoms associated with PTTD depend largely on the stage of the disorder. Early on, the anatomy of the foot and ankle is preserved, and there is often pain and swelling at the inside of the ankle, or in the arch of the foot. If untreated, this progresses to include physical changes in the structure of the tendon, repetitive ‘microtrauma’ and degeneration. Later on in the disease process, the tendon becomes excessively elongated, and its function is compromised. Surprisingly, in this later stage, pain in the tendon may not be quite as intense. However, the anatomical integrity of the ankle and foot become compromised, and the arch of the foot begins to collapse. When this occurs, the joints of the ankle undergo degenerative arthritic changes, causing a permanent deformity to develop, as seen in the photo below. As the deformity worsens, the outer shin bone (fibula) comes into contact with the outside of the heel bone (calcaneus). This ‘impingement’ or compression can lead to lateral ankle pain as well.29

What do I do if I think I have PTTD?

Currently, there is strong evidence to support the use of physical therapy and orthotics to address deficits and impairments related to PTTD.32 33 34 35 Research shows that patients who perform eccentric exercise demonstrate the greatest improvement in function and reduction in pain. After performing a comprehensive evaluation, a trained physical therapist will provide you with an individualized program that addresses any deficits, weaknesses, or limitations, in the entire lower extremity, that could be contributing to PTTD.

In addition to physical therapy, it has been recommended that weight loss (if indicated), limiting repetitive aggravating activities, and wearing supportive footwear can help reduce the negative effects of PTTD.36 Additionally, orthotics and bracing may be indicated. The overall goal of braces and orthotics, such as those pictured below, is to provide arch support, reduce abnormal strain to the tendon and surrounding structures, prevent abnormal mechanics and slow the development of deformity. The ‘appropriate’ amount of intervention or external support (by way of bracing or orthotic use) depends on many factors. Again, your physical therapist can help you decide what combination of interventions is right for you.

Should I get surgery?

Conservative management is recommended for a minimum of 3 months prior to considering surgical intervention.37 In general, surgical interventions are reserved for those with a fixed bony deformity and arthritic changes (stage IV PTTD). All surgical options will involve a correction of the bony deformity prior to addressing any muscle, tendon, or ligament soft pathology. A few examples of surgical options are listed below:

- Flexor Digitorum Longus Transfer

- MCO usually performed prior to transfer of tendon

- Physical therapy will generally begin 5-6 weeks post-op40

- Lateral Column Lengthening

- With severe flatfoot deformity, the outer ankle becomes shortened compared to the inside

- Opening wedge osteotomy is performed on the heel bone (calcaneus)41 in order to improve the alignment of the outer ankle

Long story short, if you experience Shin Pain –

get yourself a good Physical Therapist!

At VASTA, our Physical Therapists have extensive advanced training

in various orthopedic injuries, including shin pain.

Click here to request an evaluation with one of our Expert Physical Therapists today.

Or call us directly at 802-399-2244

- Newman, P., Witchalls, J., Waddington, G., & Adams, R. (2013). Risk factors associated with medial tibial stress syndrome in runners: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open access journal of sports medicine, 4, 229.

- Moen, M. H., Holtslag, L., Bakker, E., Barten, C., Weir, A., Tol, J. L., & Backx, F. (2012). The treatment of medial tibial stress syndrome in athletes; a randomized clinical trial. Sports Medicine, Arthroscopy, Rehabilitation, Therapy & Technology, 4(1), 12.

- Galbraith, R. M., & Lavallee, M. E. (2009). Medial tibial stress syndrome: conservative treatment options. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine, 2(3), 127-133.

- Newman, P., Witchalls, J., Waddington, G., & Adams, R. (2013). Risk factors associated with medial tibial stress syndrome in runners: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open access journal of sports medicine, 4, 229.

- Moen, M. H., Bongers, T., Bakker, E. W., Zimmermann, W. O., Weir, A., Tol, J. L., & Backx, F. J. G. (2012). Risk factors and prognostic indicators for medial tibial stress syndrome. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 22(1), 34-39.

- Galbraith, R. M., & Lavallee, M. E. (2009). Medial tibial stress syndrome: conservative treatment options. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine, 2(3), 127-133.

- Newman, P., Witchalls, J., Waddington, G., & Adams, R. (2013). Risk factors associated with medial tibial stress syndrome in runners: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open access journal of sports medicine, 4, 229.

- Moen, M. H., Bongers, T., Bakker, E. W., Zimmermann, W. O., Weir, A., Tol, J. L., & Backx, F. J. G. (2012). Risk factors and prognostic indicators for medial tibial stress syndrome. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 22(1), 34-39.

- Galbraith, R. M., & Lavallee, M. E. (2009). Medial tibial stress syndrome: conservative treatment options. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine, 2(3), 127-133.

- Newman, P., Witchalls, J., Waddington, G., & Adams, R. (2013). Risk factors associated with medial tibial stress syndrome in runners: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open access journal of sports medicine, 4, 229.

- Newman, P., Witchalls, J., Waddington, G., & Adams, R. (2013). Risk factors associated with medial tibial stress syndrome in runners: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open access journal of sports medicine, 4, 229.

- Moen, M. H., Bongers, T., Bakker, E. W., Zimmermann, W. O., Weir, A., Tol, J. L., & Backx, F. J. G. (2012). Risk factors and prognostic indicators for medial tibial stress syndrome. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 22(1), 34-39.

- Niemuth, P. E., Johnson, R. J., Myers, M. J., & Thieman, T. J. (2005). Hip muscle weakness and overuse injuries in recreational runners. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 15(1), 14-21.

- Moen, M. H., Bongers, T., Bakker, E. W., Zimmermann, W. O., Weir, A., Tol, J. L., & Backx, F. J. G. (2012). Risk factors and prognostic indicators for medial tibial stress syndrome. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 22(1), 34-39.

- Wilder, R. P., & Sethi, S. (2004). Overuse injuries: tendinopathies, stress fractures, compartment syndrome, and shin splints. Clinics in sports medicine, 23(1), 55-81.

- Wilder, R. P., & Sethi, S. (2004). Overuse injuries: tendinopathies, stress fractures, compartment syndrome, and shin splints. Clinics in sports medicine, 23(1), 55-81.

- Loudon, J. K., & Dolphino, M. R. (2010). Use of foot orthoses and calf stretching for individuals with medial tibial stress syndrome. Foot & ankle specialist, 3(1), 15-20.

- Brennan, F. H., & Kane, S. F. (2003). Diagnosis, treatment options, and rehabilitation of chronic lower leg exertional compartment syndrome. Current sports medicine reports, 2(5), 247-250.

- Frontera, W. R., Silver, J. K., & Rizzo, T. D. (2018). Essentials of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Elsevier.

- Frontera, W. R., Silver, J. K., & Rizzo, T. D. (2018). Essentials of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Elsevier.

- Tucker, A. K. (2010). Chronic exertional compartment syndrome of the leg. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 3(1-4), 32.

- Brennan, F. H., & Kane, S. F. (2003). Diagnosis, treatment options, and rehabilitation of chronic lower leg exertional compartment syndrome. Current sports medicine reports, 2(5), 247-250.

- Tucker, A. K. (2010). Chronic exertional compartment syndrome of the leg. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 3(1-4), 32.

- Frontera, W. R., Silver, J. K., & Rizzo, T. D. (2018). Essentials of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Elsevier.

- Schubert, A. G. (2011). Exertional compartment syndrome: review of the literature and proposed rehabilitation guidelines following surgical release. International journal of sports physical therapy, 6(2), 126.

- Collins, C. K., & Gilden, B. (2016). A non-operative approach to the management of chronic exertional compartment syndrome in a triathlete: a case report. International journal of sports physical therapy, 11(7), 1160.

- Giza, E., Cush, G., & Schon, L. C. (2007). The flexible flatfoot in the adult. Foot and ankle clinics, 12(2), 251-271.

- Johnson, K. A., & Strom, D. E. (1989). Tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 239, 196-206.

- Bubra, P. S., Keighley, G., Rateesh, S., & Carmody, D. (2015). Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction: an overlooked cause of foot deformity. Journal of family medicine and primary care, 4(1), 26.

- Beals, T. C., Pomeroy, G. C., & Arthur Manoli, I. I. (1999). Posterior tibial tendon insufficiency: diagnosis and treatment. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 7(2), 112-118.

- Giza, E., Cush, G., & Schon, L. C. (2007). The flexible flatfoot in the adult. Foot and ankle clinics, 12(2), 251-271.

- Alvarez, R. G., Marini, A., Schmitt, C., & Saltzman, C. L. (2006). Stage I and II posterior tibial tendon dysfunction treated by a structured nonoperative management protocol: an orthosis and exercise program. Foot & ankle international, 27(1), 2-8.

- Kulig, K., Reischl, S. F., Pomrantz, A. B., Burnfield, J. M., Mais-Requejo, S., Thordarson, D. B., & Smith, R. W. (2009). Nonsurgical management of posterior tibial tendon dysfunction with orthoses and resistive exercise: a randomized controlled trial. Physical Therapy, 89(1), 26-37.

- Kulig, K., Lederhaus, E. S., Reischl, S., Arya, S., & Bashford, G. (2009). Effect of eccentric exercise program for early tibialis posterior tendinopathy. Foot & ankle international, 30(9), 877-885.

- Kulig, K., Popovich Jr, J. M., Noceti-Dewit, L. M., Reischl, S. F., & Kim, D. (2011). Women with posterior tibial tendon dysfunction have diminished ankle and hip muscle performance. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy, 41(9), 687-694.

- Beals, T. C., Pomeroy, G. C., & Arthur Manoli, I. I. (1999). Posterior tibial tendon insufficiency: diagnosis and treatment. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 7(2), 112-118.

- Geideman, W. M., & Johnson, J. E. (2000). Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 30(2), 68-77.

- Giza, E., Cush, G., & Schon, L. C. (2007). The flexible flatfoot in the adult. Foot and ankle clinics, 12(2), 251-271.

- Hadfield, M. H., Snyder, J. W., Liacouras, P. C., Owen, J. R., Wayne, J. S., & Adelaar, R. S. (2003). Effects of medializing calcaneal osteotomy on Achilles tendon lengthening and plantar foot pressures. Foot & ankle international, 24(7), 523-529.

- Giza, E., Cush, G., & Schon, L. C. (2007). The flexible flatfoot in the adult. Foot and ankle clinics, 12(2), 251-271.

- Giza, E., Cush, G., & Schon, L. C. (2007). The flexible flatfoot in the adult. Foot and ankle clinics, 12(2), 251-271.