Golf Injuries

About 55 million people in 206 countries worldwide play golf, making it one of the most popular sports in the world.1 With this many participants, injuries are bound to happen and understanding how and why these injuries happens is crucial to recovery and getting back out on the course injury-free. It has been reported that there is a lifetime injury incidence between 25.2% and 67.4% in adult amateur golfers.2 In other words, up to ⅔ of golfers may experience some type of injury at some point in their playing career. In professional golf, these men and women are playing more frequently and more often, and as a result, they are injured more frequently – with annual injury rates in this population between 31.0% and 90.0%!3 The spine, and in particular the low back, account for the greatest overall incidence of injury in amateur golfers at a rate of 18.3–36.4%.4 While an injury can happen to any body part while playing golf, the elbow (8.0–33.0%), the wrist and hand (10.0–32%), and the shoulder (4.0–18.6%) are other frequently injured anatomical regions in amateur golfer. We will discuss each body region in detail and the impact golf has on each injury.

Low Back Pain

Despite being viewed in the general public’s eye as a ‘casual’ sport, the truth behind the golf swing is that it is a dynamic, explosive, and powerful movement, especially for the spine and low back. In fact, researchers have studied golfers in a lab and found compression loads of up to 8x a person’s body weight, or about 6,100 Newtons, during the golf swing.5 For comparison, a study by the same authors using similar techniques measured lumbar compression forces in Division 1-A college football linemen to be about 8,679 N when hitting a blocking sled.6 Now, imagine that load on the spine 70-85 times throughout the course of a full round of golf, and it’s no wonder low back pain is the number one injury experienced by golfers!

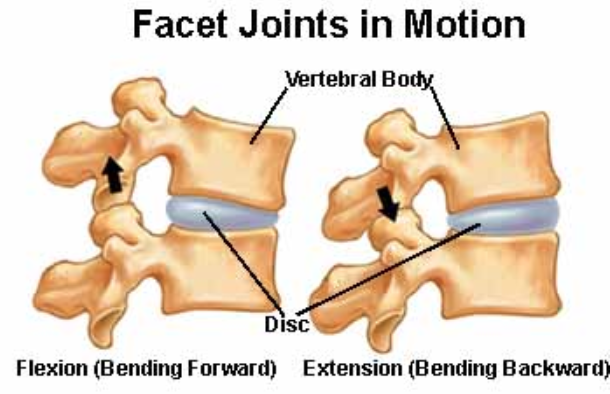

The joints of the lumbar spine, also known as facets, are oriented in a fashion that allows us to bend and extend our low back very well, but they limit the amount of rotation and lateral bending we are able to achieve.

Inherently, the golf swing, which is multiplanar in nature, forces the athlete to move into restrictions of motion that are unnatural for the lumbar spine.

So, how do we achieve the motion necessary to perform a proper backswing and follow through without putting undue stress on the low back? Other parts of our body have to move efficiently and effectively, namely the hips, thoracic spine (mid back), and shoulders.

Studies show that side-to-side differences in hip internal rotation range of motion was more likely to occur in those with low back pain, with those having low back pain demonstrating reduced motion in the lead hip.7 For example, if a right handed golfer is unable to effectively internally rotate their lead hip (left hip) during the downswing and follow through, the lumbar spine has to go into greater rotation in order for the golfer to achieve an effective shot. Given the high loads placed on the spine during a “normal” swing (discussed above), any compensation or deviation that increases stress and strain can quickly become a problem.

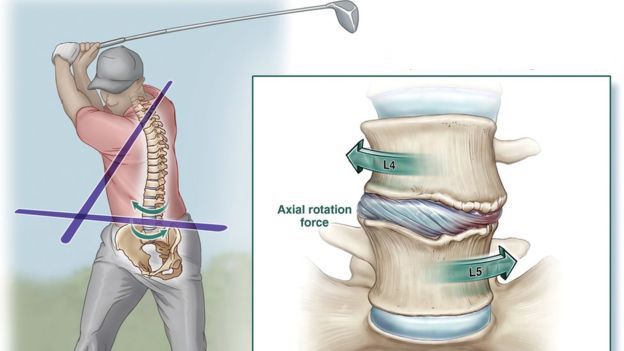

In today’s golf swing, the idea is to create as much dissociation of the hips, low back, and upper body in order to develop and store potential energy with the backswing, making the downswing and follow through more powerful. This dissociation is known as the ‘hip-shoulder separation angle.’ Maximizing this angle does increase power with the golf swing, but it also increases the torsional load in the spine, and it serves to further stretch the “viscoelastic elements” (discs, ligaments, tendons, etc.).

This separation angle is also known as the ‘‘X-factor’’ due to the ‘‘X’’ made by lines drawn along the axial orientation of the shoulders and hips at the transition between the end of the backswing and start of the forward swing.

According to a study by Lindsay et al,8 golfers with LBP consistently exceeded their trunk rotation during their swings when compared with rotation in neutral posture at a controlled speed.

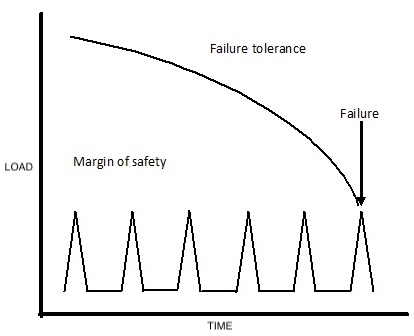

The authors argue that this supramaximal rotation places excessive strain on viscoelastic structures in the spine beyond their physiologic range of flexibility, thereby reducing the threshold for injury.9 This repeated torsional stress on the discs and ligaments of the spine can lead to recurring pain and limitations over the course of time.

Downswing and Follow Through

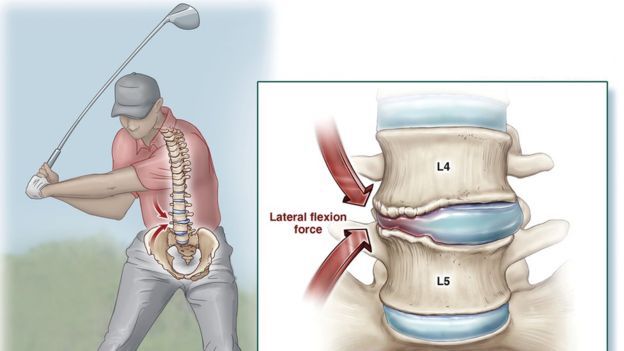

During the downswing and follow through phase of the golf swing there is increased lateral bending towards the trailing side (right side for a right handed golfer). As the golfer attempts to generate more force behind the ball at impact, there is increased side bending of the spine. The amount of lateral bending can be measured both directly and through the ‘‘crunch factor.’’ Its clinical application is controversial because of lack of supporting evidence, but it is defined as the product of the lumbar lateral bending angle and axial rotation velocity.10

The “crunch factor” is basically a term used in research studies and in labs that look at how lateral bending and rotation affect a golfer’s lower back. It is described as the combination of side bending and rotation during the downswing phase of the swing.11 When you consider the rapid stress to the trailing side of the lower back (as seen in the figure above), it makes sense that the joints of the lower back and trailing side undergo high levels of stress, creating a potential source for back pain in the golfing community.

Not surprising, amateurs, who generally have more swing irregularities, generate approximately 80% greater peak lateral bending and shear loads than professionals.12

Follow Through

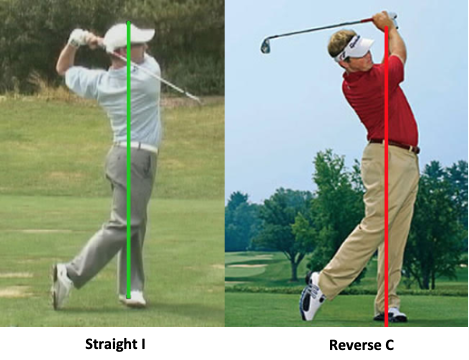

The final phase of the golf swing is the follow through phase, which occurs after the ball has been impacted and it’s flying down the fairway…or into the woods. One common swing mistake is the reverse “C” posture (see the figure below). As you can see in the image on the left, the golfer’s hips finish in front of the lower back, mid back, shoulders, and head and neck. This finishing posture results in maximal extensor muscle contraction, further increasing compressive forces on the spine.13 Microtrauma to the hyperlordotic spine (excessively arched like in the picture) secondary to repetitive hyperextension activities has been implicated in the etiology of spondylolysis, (stress fracture) – yikes!

Risk Factors for Developing Low Back Pain (LBP) in Golfers

- Greater age is associated with an increased risk of developing LBP14

- Higher body mass is associated with LBP in golfers relative to healthy controls15

- Playing more rounds and hitting more shots per week are associated with higher rates of LBP16

- Individuals who carry their golf bag are more likely to experience LBP17

- Side to side asymmetry of side plank endurance (core strength and endurance) was significantly associated with development of LBP18

- Golfers with LBP demonstrate reduced trunk strength in all planes of movement19

- Side to side differences in hip internal rotation ROM was more likely to occur in those with LBP, with those having LBP demonstrating reduced motion in the lead hip

- The strongest predictor of golf-related LBP is a prior history of LBP20

Preventing Low Back Injuries

Now that we know why the lower back is so commonly involved as a source of pain, and what the risk factors are, how do golfers minimize their risk? All things considered equal, there are a few easy steps that all golfers can take in order to minimize the risk, regardless of injury.

Easy Modifications for All Golfers In Order to Reduce Risk for Developing LBP

- Work with a PGA professional in order to ensure proper technique and club size

- Use a push cart, ride in a cart, or utilize a caddy so that you don’t have to carry your bag

Note: if you do have to carry a bag, utilize two straps rather than one in order to distribute loads evenly on the spine

- Participate in a training program in the off season and during the golfing season, focusing on hip mobility and hip and core strength and endurance

- Keep your body weight in check! A higher body mass index is associated with LBP in golfers.

- Be strategic and deliberate about calculating playing volume and avoid ramping up volume too quickly. More strokes = more volume and more stress on the spine, leading to a higher likelihood of injury. Simply put, a golfer who plays 7 rounds of golf per week is more likely to experience LBP compared to a golfer who plays 2 rounds per week.

- Never try to play through LBP. Remember, the #1 predictor of LBP is a history of LBP

Elbow

Injuries to the elbow are far less common compared to the back, with injury rates ranging between 8 and 30% of golf related injuries.21 Compared to low back injuries, which tend to occur in older golfers, elbow, wrist and hand injuries are more common in those ages 25-37.22 Far and away the most common elbow injuries, especially in amateur golfers are “golfer’s elbow” (no surprise there), and “tennis elbow.” Despite these two injuries having different names, treatment and care for each is similar, so we will discuss them together.

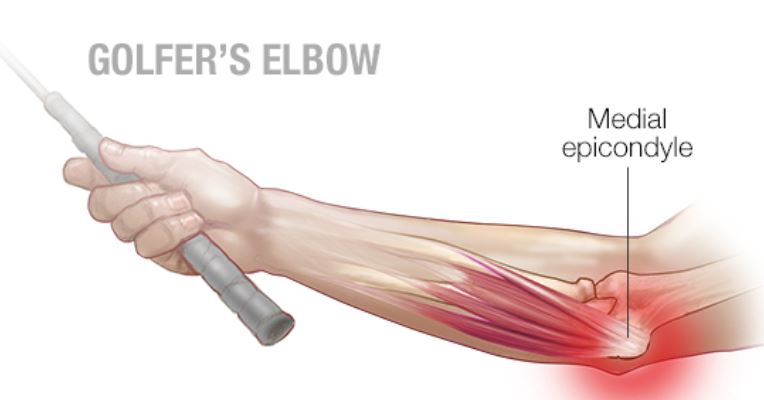

Medial epicondylitis is also known as ‘Golfer’s Elbow.’ Despite its name, it is actually less common than tennis elbow in golfers – more to come on that soon! This injury affects the inside of the elbow at the medial epicondyle of the humerus (upper arm bone). Medial epicondylitis typically affects the trailing arm of the golfer, affecting the right elbow of a right handed golfer. It is most likely caused by sudden impact loading, such as striking the ground, encountering unexpected obstacles, or taking repetitive strokes that leave large divots. Ulnar neuritis, or irritation and inflammation of the ulnar nerve (immediately adjacent to the epicondyle) is associated with medial epicondylitis in as much as 20% of cases.23 This could cause numbness and tingling along the inner forearm and pinky and ring fingers if present. At times, this injury can be traumatic (striking the ground), but in the vast majority of cases, this injury typically comes over time and is caused by repetition. The tendinous insertion point of the wrist flexors at the elbow can get inflamed, leading to pain.

Lateral elbow pain is more common than medial elbow pain by a 5:1 ratio in amateur golfers.24 This condition is not necessarily specific to golfers as it’s a common reason adults seek the care of a physical therapist. Lateral epicondylitis is caused by repetitive forceful contraction of the wrist extensors and typically, the load and stress to the lateral elbow is increased with twisting, or rotation of the forearm, as seen in the golf swing. In addition, it is associated with gripping the club too tightly. For a more detailed explanation of lateral epicondylitis, check out our detailed blog post here.

Treatment for golfer’s elbow and tennis elbow depends on how long the problem has been present. If the pain and injury is more acute, treatment includes rest, ice, compression, and elevation and the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to reduce inflammation. Tennis elbow straps can be used to allow decreased pain if golfing must continue, but their use is largely anecdotal and the research around this topic is limited and conflicting. The mechanism of the tennis elbow strap is to cinch down the proximal forearm musculature to a point that the forced contraction is decreased – by effectively shortening the length of the muscles.

For injuries and pains that have been ongoing, muscle-tendon strengthening within the limits of pain is the gold standard for treatment. A physical therapist will work with the athlete to determine an optimal level of loading at the musculotendinous junction in order to improve the tensile strength of the tendons where they attach onto the bone. Research suggests that an eccentric strengthening program should elicit low levels of pain (2-3 on a 10-point scale), so it’s important to note that this intervention may not be pain free – that’s okay and actually necessary for long term success!

For more information specific to treatment of Tennis Elbow – See our Blog here.

A randomized control trial by Svernlov and Adolfsson25 found that regardless of the duration of symptoms, the most effective therapeutic intervention for lateral epicondylitis is eccentric training – a strong argument for its use! In 2007, Croisier et al.26 performed an intervention study on 92 patients with lateral elbow pain. At the conclusion of the experiment, the eccentric training group had significantly less pain, mitigated bilateral strength deficits, improved tendon integrity (e.g., showed evidence of pathology resolution), and improved disability status when compared with the control group.

Shoulder

While low back pain and elbow injuries are the two most commonly injured body region in golfers, shoulder injuries are also not uncommon. In amateur golfers, injury rates to the shoulder range from 4-18.6%.27 Shoulder injuries happen to golfers of all ages, but the occurrence rate increases with age. The mean age for shoulder injury in adult golfers is 63.5 years old,28 perhaps indicating that degenerative rotator cuff injuries are common in the golfing population. Like other golf injuries, injury to the rotator cuff can range from an acute strain to repetitive irritation and tendinitis to a degenerative rotator cuff tear. The details of each of these diagnoses are outlined in our detailed blog about rotator cuff injuries.

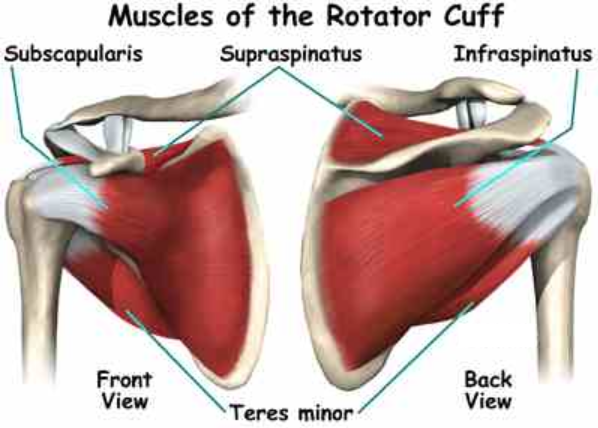

Four muscles make up the rotator cuff, including the subscapularis, infraspinatus, supraspinatus, and teres minor. A study by McHardy et al.29 looking at muscle activity during the golf swing found that the muscles of the rotator cuff are most active during the follow through phase of the swing. Contrary to popular belief, the rotator cuff doesn’t work that much during the backswing or the initiation of the downswing – the lower body and the torso are the most active during this phase. This is important to understand because the rotator cuff primarily helps to slow down the arms and the golf club after the ball has already been struck. These repeated high eccentric loads to the cuff can lead to injury over time.

During the follow through, the lead shoulder goes into external rotation while the trailing shoulder goes into internal rotation. As a result, the muscles that control these movements help to slow down the shoulders and the club. This eccentric muscle activity allows for an efficient follow through and helps the athlete avoid overswinging.

Because of the close relationship between the thoracic spine (mid back) and shoulders, golfers with a lack of trunk rotation range of motion may require the smaller shoulder rotators (teres minor and infraspinatus) to become excessively active to maintain the swing momentum or decelerate the club.30 As a result, a lack of trunk rotation range of motion is a predisposing risk factor for rotator cuff injury in the golfing population. For other risk factors, see the table below.

Predisposing Risk Factors for Rotator Cuff Injuries in Golfer31

- Reduced of trunk rotation range of motion (ROM)

- Poor trunk/hip dissociation, leading excessive reliance on the shoulder

- Rotator cuff weakness and weakness of the scapular stabilizers

- Reduced shoulder external rotation ROM in the trailing shoulder

- Using a shorter backswing 32

Golf is a frequent source of aches, pains, and injury, especially if you play multiple rounds each week. If you are struggling with an injury that’s hampering your performance, or keeping you off the course completely, see our Titleist Performance Institute (TPI) and orthopedic clinical specialist physical therapist, Matthew Betz for a Golf Swing Analysis. OR, if you want to prevent injury and perform your best when on the course, see our TPI certified performance coach and trainer, Matt Vosburgh.

VASTA is the region’s premier sports physical therapy and sports training facility. With two TPI professionals under one roof, VASTA is the place to go if you want to get back on the course, prevent injury, and perform optimally.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

you are doing a great job, and up to date with technology

Hi, I’m new to golf. I have felt back pain yesterday. I wasn’t able to understand what’s the reason behind it. Thanks for writing an amazing article based on it. It helped me so much. Once again, thanks.

VERY happy to hear!

You are not alone (obviously). The very best golfers in the world (with access to world class care) suffer from Low Back Pain.

There is no ‘simple’ solution or single ‘answer’ for everyone. We’re glad this info was valuable. Keep after it!

Great article to help people pay more attention to the physical injuries that golf may cause, so that they can protect their bodies from injuries

I have enjoyed reading your article, so I felt I would comment to tell you. Cheers for taking a moment to write.