Introduction

Plantar fasciitis (PF) is the most common foot condition seen in Physical Therapy clinics across the country,1 and has been reported to be the most common foot condition diagnosed and treated in Sports Medicine centers,2 effecting ~ 2 million Americans / year. About 10% of the general population will experience plantar fascia pain at some point throughout their life 3 and the risk for developing PF increases with an active lifestyle and/or sports participation.

Other factors that contribute to the development of PF include: 4

- A Job that requires prolonged time standing / weight bearing

- A sudden increase in weight bearing or impact activities e.g. an indoor cyclist who suddenly starts hiking 10+ miles /day in the Spring time, or a runner who decides to ramp up weekly mileage from 15 to 35, all at once.

- Age (Over 40)

- Decreased calf flexibility

- Flat feet (high pronation / low arch)

- Overweight (BMI > 30) * this has been shown as a risk factor in the non-athletic population

What is it?

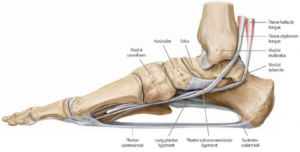

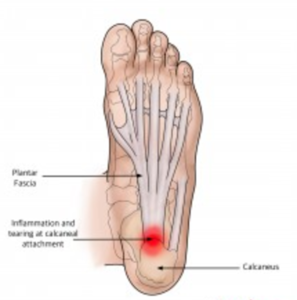

The plantar fascia is a fibrous ligament that supports the arch of the foot. It is technically made up of 3 bands (a lateral, medial and central band).

The plantar fascia is a fibrous ligament that supports the arch of the foot. It is technically made up of 3 bands (a lateral, medial and central band).

Think about an archery bow placed on the ground, string down. The bow represents the bones of the foot and the string represents the plantar fascia.

With each step, the arch flattens a bit, transferring load to the fascia. If the load is not controlled, with enough repetitions microscopic tears will begin to accumulate until the integrity of the structure is compromised.

How to diagnose it?

A Diagnosis of Plantar Fasciitis can typically be made clinically. Diagnostic imaging (X-ray, MRI, Ultra Sound, etc.) is rarely needed unless other related injuries (e.g. a stress fracture) needs to be ruled out.

Importantly, patients with PF will occasionally come into the clinic with x-rays and a ‘diagnosis’ of a heel spur (a boney build up at the insertion point of the plantar fascia). This is not a diagnosis! The ‘spurring’ is a result of stress at this insertion point… in other words, this is a symptom of the problem, not the problem it’s self.

Studies have shown that these heel spurs are present in almost 50% of people without any complaints of plantar fascia or heel pain. 5

Your Physical Therapist can diagnose PF with a series of clinical tests and careful/deliberate palpation.

What does it feel like?

Typically the first symptom is pain at the heel bone, where the ligament attaches. Heel pain, more so than arch pain, is often (although not always) the primary complaint. Plantar Fasciitis accounts for ~ 80% of all heel pain; so, if you’re ramping up your outdoor activity, and you have been experiencing heel pain, there’s a good chance your Plantar Fascia is the culprit.

A typical presentation includes:

- Pain that is most prominent first thing in the morning, or upon rising from prolonged sitting

- Pain that decreases with movement (at least at first)

- Pain perceived as ‘sharp’ and ‘searing’

What causes it?

In a word (or 2) – Repetitive Stress.

While damage to the fascia can result from a single traumatic injury, the development of PF is almost always due to repetitive strain.

Sports Physical Therapists see quite a bit of Plantar Fasciitis related to 2 key factors:

Biomechanical Dysfunction AND/OR Training Errors.

1) Biomechanical Dysfunction – Runners and running athletes may be at risk of developing PF if their gait pattern places high demands on the arch and/or rearfoot. Examples of common findings include a toe-out gait, excessive pronation,6 heel striking with the foot in full ‘Dorsiflexion’ (toe-up position).7 Also, runners demonstrating high ‘impact rates’ have been shown to increase stress to the plantar Fascia. 8 (See here for a more detailed explanation for gait mechanics and considerations for injury risk and here for information on VASTA’s running assessment.)

These athletes may benefit from gait modifications – small little ‘tweaks’ and/or guided imagery to reduce repetitive stress loading to the fascia.

2) Training Errors – Rapid increases in running volume and/or a sudden increase in time spent on your feet for any reason, are common examples of ‘training errors’ that may lead to PF.

I often find myself telling patients: “The body will adapt to slow incremental changes, but it will react to large or sudden changes.”

What to do?

Consult with a Sports Physical Therapist to:

- Identify training errors.

Click here to read more about common training errors and how to avoid them.

- Take a look at your shoe wear.

Switching into ‘spring’ shoe wear may be setting you up for injury. Flip-flops are a killer; and hyper-flexible shoes of any type are a risk factor

* For those minimalist runners out there – don’t get your undies in a bunch. While slowly transitioning into super-flexible shoes can be safely and effectively done for some, a sudden switch to flimsy footwear is problematic.

- Address faulty biomechanics

All Runners and Running athletes should have a comprehensive gait analysis performed.

- Improve mobility

Your PT will utilize a combination of hands-on techniques. These may include (as appropriate): Soft Tissue mobilization to the calf muscles and arch, Joint Mobilizations to the foot and ankle, Instrumented Soft Tissue Mobilization directly to the fascia, and Nerve mobilization techniques to entrapment sites of the medial and/or lateral plantar nerve immediately adjacent to the plantar fascia.

These hands-on approaches have been shown to be beneficial in patients with persistent PF 9 10

- Develop a corrective flexibility routine

The fibers that make up our plantar fascia are continuous (in part) with the fibers that make up your Achilles Tendon (the heel cord).11 Tightness of the calf muscles increases the stress to the fascia, and we already stated that decreased ankle mobility is a risk factor for developing PF.12 Thus, it makes sense for patients suffering from PF to stretch the calf’s (aggressively), and the research supports the effectiveness here 13 as well as for interventions that stretch the fascia it’s self . 14

Other common areas in need of ‘mobilization’ include the hip flexors as tightness here can lead to early ‘heel up’ while running.

- Develop a corrective flexibility routine

This includes addressing and weakness of muscles that directly support the arch of the foot (and therefore reduce strain to the fascia) AND addressing any weakness of muscles that are found to be functioning sub-optimally during the gait analysis.

Taping techniques specifically designed to reduce stress to the plantar Fascia may be utilized. This has been shown to be effective at immediately reducing pain and allowing to short term ‘break’ for these tissues 15 16 17

Additionally, your Physical Therapist may suggest iontophoresis treatments – the delivery of topical medication (0.4% dexamethasone sodium phosphate) through the skin with use of an electrically charged pad. This appears to improve symptoms only acutely, and only in patients willing to perform the treatments regularly (at least 2 x/week for 2-3 weeks). 18 19 Given that the ‘added’ benefit of this treatment is short term only (addressing biomechanical issues and mobility deficits are what really ‘fix’ the issue) it should be used only in patients with important short-term goals in mind (e.g. competing in a 10K in 2 weeks). Otherwise, it may not be worth the added cost.

Last, but importantly, your PT will ensure other issues that can cause heel / foot pain are not present. This includes Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome, Calcaneal Stress Fractures, Bone Bruises, ‘Fat Pad Syndrome’, Medial or Lateral Plantar Nerve entrapments, and referred pain from the back (S1 Radiculopathy).20 21 22

Other Treatments?

- Orthotics

Orthotics are occasionally prescribed for PF. We offer custom fabricated orthotics here at VASTA and our Sports Physical Therapists are lower extremity biomechanics experts. However, we suggest custom orthotics only in the minority of cases. We suggest custom orthotics in cases of significant foot/ankle mal-alignment OR as a ‘short term’ fix in extreme cases. Put another way, an orthotic may be in much the same way that a pair of crutches would – to reduce stress to a particular areas, for a period of time to allow for healing to take place.

The association between foot ‘structure’, alignment or movement with the development of PF is largely inconclusive. 23 While some studies have demonstrated a positive effect with custom orthotics, 24 25 especially when combined with other interventions (such as stretching and strengthening), 26 other studies have failed to show a benefit. 27

Our contention is that this ‘mixed bag’ of research findings is due to the fact that most studies look into the effectiveness of orthotics for all patients with PF, whereas only a select sub-group are most likely to benefit (or require) this intervention.

- Night Splints

Night splints are commonly recommended for patients with PF. While there is research in support of utilizing night splints 28 29 30 we do not routinely recommend their use as an initial intervention due to the fact that splints must typically be worn for a prolonged period of time (1-3 months) to achieve the desired effect 31 AND they are often not well tolerated by patients. For this reason, we approach PF with interventions described above and recommend a trial of night splinting only for cases that are unresponsive to traditional approaches.

- Steroid Injections

For particularly troublesome cases, patients may be referred for a steroid injection. The evidence to support the effectiveness of steroid injection is limited, and suggests only a short-term effect.32 A major concern with steroid injection is the risk of subsequent plantar fascia rupture and/or fat pad degeneration. One large retrospective study (of 765 patients) showed that 36% of patients who received a steroid injection had a fascial rupture as a result of the injection. Other studies have shown greatly reduce risk of PF rupture with Ultrasound guided injections. 33 34 Ultrasound guided injections also seem to have a greater mid>long term effect (a lower recurrence rate 4-6 week out from injection) 35 and a confirmed reduction in fascia thickness on ultrasound (a sign of Fasciitis) both acutely and at 6 month follow up (e.g. maybe not just a short term relief). 36

- Platelet Rich Plasma Injections

While the research is still somewhat limited, for cases of chronic and severe plantar Fasciitis, PRP injections appear to have some value when compared to Steroid Injection. 37

- Surgical Release

Surgical Release of the fascia is an option for persistent and extreme cases. A particularly good study performed in 2016 shed some light on why this should be avoided if at all possible!38 The surgeons followed 24 patients over a period of ~ 6+ years. They offered 2 important findings – 1) Receiving steroid injections prior to surgery had a very negative effect on the outcome (steroid injections are known to have effects detrimental to the healing capacity of tissues) AND 2) Given the “prolonged recovery period and generally poor outcomes leads the authors to suggest that open plantar fascia release is of questionable clinical value” – Not exactly a vote of confidence.

If you are experiencing any signs or symptoms of Plantar Fasciitis and would like to consult with one of our Sports Physical Therapists – Request an Appointment Now or give us a call at 802.399.2244.

The nature of overuse injuries in general is that the quicker they are identified and treated, the quicker they may resolve. So, call us today!

- Reischl SF. Physical Therapist Foot Care Survey. Orthop Pract. 2001;13:27.

- Taunton JE, Ryan MB, Clement DB, McKenzie DC, Lloyd-Smith DR, Zumbo BD. A retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36:95-101.

- Riddle DL, Pulisic M, Pidcoe P, Johnson RE. Risk factors for Plantar fasciitis: a matched case-control study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:872-877

- Riddle DL, Pulisic M, Pidcoe P, Johnson RE. Risk factors for Plantar fasciitis: a matched case-control study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:872-877

- Osborne, H. R., Breidahl, W. H., & Allison, G. T. (2006). Critical differences in lateral X-rays with and without a diagnosis of plantar fasciitis. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 9(3), 231-237.

- Riddle DL, Pulisic M, Pidcoe P, Johnson RE. Risk factors for Plantar fasciitis: a matched case-control study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:872-877

- Pohl, M. B., Hamill, J., & Davis, I. S. (2009). Biomechanical and anatomic factors associated with a history of plantar fasciitis in female runners. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 19(5), 372-376.

- Altman, A. R., & Davis, I. S. (2016). Prospective comparison of running injuries between shod and barefoot runners. Br J Sports Med, 50(8), 476-480.

- Young B, Walker MJ, Strunce J, Boyles R. A combined treatment approach emphasizing impairment-based manual physical therapy for plantar heel pain: a case series. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34:725-733. http:// dx.doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2004.1506

- Meyer J, Kulig K, Landel R. Differential diagnosis and treatment of subcalcaneal heel pain: a case report. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2002;32:114- 122; discussion 122-114

- Snow SW, Bohne WH, DiCarlo E, Chang VK. Anatomy of the Achilles tendon and plantar fascia in relation to the calcaneus in various age groups. Foot Ankle Int. 1995;16:418-421

- Riddle DL, Pulisic M, Pidcoe P, Johnson RE. Risk factors for Plantar fasciitis: a matched case-control study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:872-877

- Porter D, Barrill E, Oneacre K, May BD. The effects of duration and frequency of Achilles tendon stretching on dorsiflexion and outcome in painful heel syndrome: a randomized, blinded, control study. Foot Ankle Int. 2002;23:619-624.

- DiGiovanni BF, Nawoczenski DA, Lintal ME, et al. Tissue-specific plantar fascia-stretching exercise enhances outcomes in patients with chronic heel pain. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:1270-1277.

- Osborne HR, Allison GT. Treatment of plantar fasciitis by LowDye taping and iontophoresis: short term results of a double blinded, randomised, placebo controlled clinical trial of dexamethasone and acetic acid. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:545-549

- Radford JA, Landorf KB, Buchbinder R, Cook C. Effectiveness of low-Dye taping for the short-term treatment of plantar heel pain: a randomised trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:64.

- Hyland MR, Webber-Gaffney A, Cohen L, Lichtman PT. Randomized controlled trial of calcaneal taping, sham taping, and plantar fascia stretching for the short-term management of plantar heel pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36:364-371.

- Gudeman SD, Eisele SA, Heidt RS, Jr., Colosimo AJ, Stroupe AL. Treatment of plantar fasciitis by iontophoresis of 0.4% dexamethasone. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:312-316.

- Osborne HR, Allison GT. Treatment of plantar fasciitis by LowDye taping and iontophoresis: short term results of a double blinded, randomised, placebo controlled clinical trial of dexamethasone and acetic acid. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:545-549

- Alvarez-Nemegyei J, Canoso JJ. Heel pain: diagnosis and treatment, step by step.Cleve Clin J Med. 2006;73:465-471.

- Buchbinder R. Clinical practice. Plantar fasciitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2159-2166.

- Greene DL, Thompson MC, Gesink DS, Graves SC. Anatomic study of the medial neurovascular structures in relation to calcaneal osteotomy. Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22:569-571.

- Irving DB, Cook JL, Menz HB. Factors associated with chronic plantar heel pain: a systematic review. J Sci Med Sport. 2006;9:11-22; discussion 23- 24.

- Lynch DM, Goforth WP, Martin JE, Odom RD, Preece CK, Kotter MW. Conservative treatment of plantar fasciitis. A prospective study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1998;88:375-380.

- Turlik MA, Donatelli TJ, Veremis MG. A comparison of shoe inserts in relieving mechanical heel pain. Foot. 1999;9:84-87.

- Pfeffer G, Bacchetti P, Deland J, et al. Comparison of custom and prefabricated orthoses in the initial treatment of proximal plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20:214-221.

- Martin JE, Hosch JC, Goforth WP, Murff RT, Lynch DM, Odom RD. Mechanical treatment of plantar fasciitis. A prospective study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2001;91:55-62.

- Powell M, Post WR, Keener J, Wearden S. Effective treatment of chronic plantar fasciitis with dorsiflexion night splints: a crossover prospective randomized outcome study. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19:10-18.

- Roos E, Engstrom M, Soderberg B. Foot orthoses for the treatment of plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27:606-611.

- Barry LD, Barry AN, Chen Y. A retrospective study of standing gastrocnemius-soleus stretching versus night splinting in the treatment of plantar fasciitis. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2002;41:221-227

- Osborne HR, Breidahl WH, Allison GT. Critical differences in lateral X-rays with and without a diagnosis of plantar fasciitis. J Sci Med Sport. 2006;9:231- 237.

- Crawford F, Thomson C. Interventions for treating plantar heel pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;CD000416.

- Genc H, Saracoglu M, Nacir B, Erdem HR, Kacar M. Long-term ultrasonographic follow-up of plantar fasciitis patients treated with steroid injection. Joint Bone Spine. 2005;72:61-65.

- Tsai WC, Hsu CC, Chen CP, Chen MJ, Yu TY, Chen YJ. Plantar fasciitis treated with local steroid injection: comparison between sonographic and palpation guidance. J Clin Ultrasound. 2006;34:12-16.

- Tsai WC, Hsu CC, Chen CP, Chen MJ, Yu TY, Chen YJ. Plantar fasciitis treated with local steroid injection: comparison between sonographic and palpation guidance. J Clin Ultrasound. 2006;34:12-16.

- Genc H, Saracoglu M, Nacir B, Erdem HR, Kacar M. Long-term ultrasonographic follow-up of plantar fasciitis patients treated with steroid injection. Joint Bone Spine. 2005;72:61-65.

- Monto, R. R. (2014). Platelet-rich plasma efficacy versus corticosteroid injection treatment for chronic severe plantar fasciitis. Foot & ankle international, 35(4), 313-318.

- MacInnes, A., Roberts, S. C., Kimpton, J., & Pillai, A. (2016). Long-Term Outcome of Open Plantar Fascia Release. Foot & ankle international, 37(1), 17-23.