SWIMMER’S SHOULDER

What is it?

Shoulder pain is the most common musculoskeletal complaint in swimming with reports of disabling shoulder pain in competitive swimmers ranging from 40 > 91%. 1 2

The term ‘Swimmer’s Shoulder’ (SS) actually describes a set of symptoms common for swimmers. It doesn’t describe one specific tissue pathology.

What does it feel like?

Pain is typically in front, top or side of shoulder

Pain may be during or after swimming.

Shoulders may fatigue easily during swims (perhaps preceding the onset of pain)

Often there may be an exaggerated ‘heaviness’ or fatigue associated with lifting the arm overhead after a hard swim.

While swimming, pain may be experienced during ‘entry phase’ of stroke, at the very beginning of the ‘pull through’ phase (‘grabbing the water’), or the beginning of the ‘recovery’ phase (while the arm is exiting the water).

What Causes it?

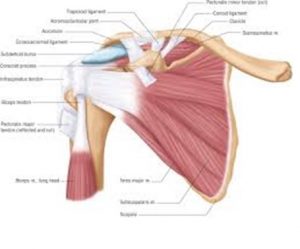

Swimming is inherently demanding of the rotator cuff muscles – especially the front and top of the rotator cuff (The Supraspinatus and Subscapularis).

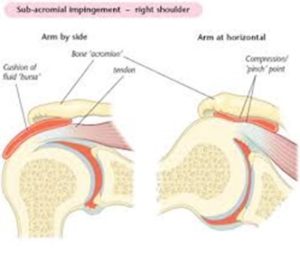

Quite commonly swimmers experience a gradual weakening of the ligaments and ‘capsule’ that support the front of the shoulder joint. 3 The ball and socket begins to demonstrate excessive mobility during a typical ‘stroke’. This, in-turn, places even more strain on the rotator cuff. If the rotator cuff cannot ‘stabilize’ the shoulder joint sufficiently, ‘sloppy’ shoulder movement results. This leads to tissue strain and inflammation in the top/front of the shoulder. Often, the result is what is termed ‘impingement’ in the shoulder joint with swimming and/or general overhead use.

| Technical Jargon

Yes, the acquired anterior laxity may be, on some level, ‘adaptive’ as it allows for greater ranges of motion (particularly external rotation), but it also places greater demand on the rotator cuff and the long head of the biceps to reduce humeral head elevation and anterior translation. Failure of the rotator cuff and the scapular stabilizers to maintain the humeral head (the ‘ball’) centered in the glenoid fossa (the ‘socket’) leads to gradual microtrauma through increased tensile stress to the supporting tendons or increased compression of tissues between the humeral head and the overlying acromion. 4 5 |

This repetitive strain leads to an accumulation of ‘micro-trauma’. This may be minimally painful at first – experienced as some soreness after swimming, ‘tightness’ the day after, etc… Nothing that the swimmer might point to as a single, acute injury until it reaches a critical threshold.

If swimming volume is high and/or ‘off days’ are few, this micro-trauma builds up.

A competitive swimmer usually exceeds 4000 strokes for one shoulder in a single workout! It’s no wonder that repetitive stress injury is common.

For the determined and competitive athlete that does not address these issues early on, the process continues and leads to worsening pain, reflexive muscle spasm in the shoulder girdle region and altered (faulty) mechanics result.

Muscle imbalances and postural distortions develop – Rounded upper backs, forward tilted shoulder blades, protracted and internally rotated shoulders. These classic postural changes, along with a compensatory ‘sway’ back in the lower back give way to the typical ‘swimmers posture’. These postural and structural changes, in turn, further perpetuate (or even accelerate) the repetitive strain experienced during swimming – The cycle of dysfunction is self-sustaining and requires a substantial effort to be broken.

What to do?

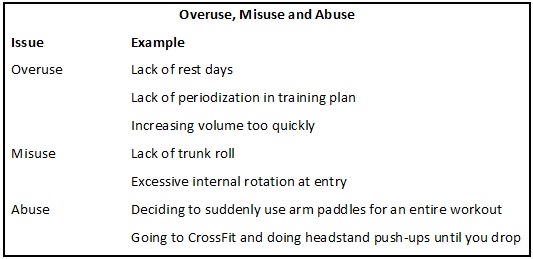

Step one is to determine if the injury is a result of overuse (training errors), misuse (form/technique errors) or abuse (being a total knuckle head).

Once form and training errors have been assessed, we turn our head to the physical ability of the body to perform the highly demanding tasks inherent to the sport of swimming. Remember, the shoulder spends 25% of the stroke cycle in a vulnerable, ‘impingement’ position with perfect form. So even when swimming properly, the athlete must be conditioned for the task.

Have Your Mobility Assessed.

Correct swimming form requires the shoulder to move through a large range of motion (ROM). Proper mobility relies on all of the many, many pieces of the ‘biomechanical chain’ that affect your shoulder’s ability to move efficiently. This includes the shoulder joint itself, the rotator cuff, the shoulder blade, the collar bone, the neck, the mid back, the rib cage, etc. You get the idea.

Meet with a Sports Physical Therapist with experience treating swimmers and make sure there are no mobility deficits that will increase strain on the shoulders.

| Correction of mobility deficits may be addressed using joint mobilization or manipulation techniques, facilitated stretching, Instrument Assisted Soft Tissue Mobilization (IASTM) to break up areas of fibrosis (or ‘adhesions’), Trigger Point Needling in muscles with excessive tone or spasm (see discussion above regarding ‘feedback loop’). |

Have Your Strength Assessed.

A thorough assessment of a swimmer’s strength is essential. Swimming demands a high level of coordination and endurance from the small rotator cuff muscles and the muscles that position and ‘stabilize’ the shoulder blade.

Maintaining balance between the strength and action of these muscles and the stronger, more ‘dominant’ muscles used during swimming is essential. Because of the powerful and repetitive internal rotation and extension of the shoulder performed by swimmers, they tend to have exceptionally strong pectoralis, triceps, and latissimus dorsi muscles. The rotator cuff and scapular muscles need to be properly trained to ‘keep up’. Any imbalance including tightness or weakness of key muscles can lead to breakdown.

Assessment of competitive athletes typically will not demonstrate that these muscles are weaker than the general population; however, these muscles are quite often weak in comparison to their own “swimming” muscles. Identifying and correcting these muscular imbalances is one of the keys to preventing and/or resolving “Swimmer’s Shoulder.”

| Common Muscles in Need of Training

1) Serratus Anterior: This muscle acts eccentrically to stabilize the scapula against the strong pull of the latissimus during the ‘catch’ and ‘pull through’. Also, the serratus is active during the ‘recovery’ phase to assist in achieving the full shoulder range of motion essential to a proper stroke. We need ~ 180 degrees of elevation for an efficient freestyle stroke. The maximal possible elevation of the arm bone (humerus) with relation to the scapula is 120 degrees. The other 60 degrees needed to fully elevate the arm comes from the upward rotation of the scapula. This 1:2 ratio is known as the ‘scapulohumeral rhythm’ – and balance of this rhythm is important. If the upward rotators of the shoulder girdle are weakened, the scapula will not move properly and the humerus will jam (or ‘impinge) into the top of the scapula. 2) Lower Trapezius: Similar to the Serratus, this muscle is active and essential during both the pull-through’ and ‘recovery’ phase. The lowed trapezius is a very common muscle to find weakness in. 3) Rotator Cuff: The ‘rotator cuff’ (RTC) is actually a series of 4 muscles. The tendons blend together somewhat to ‘cuff’ around the top of the arm bone (the ‘ball’ of the ball-in-socket joint). |

For most swimmers the front of the RTC is strong and overdeveloped, while the top and back of the RTC is may be relatively deconditioned. The top of the RTC may be weak, however, if the shoulder is already inflamed and impinging, addressing this weakness without exacerbating symptoms can be complicated.

* An individual assessment by a Sports Physical Therapist is recommended before to starting up a RTC conditioning routine.

Have Your Form Evaluated.

Have a qualified swim coach or Sports Physical Therapist with knowledge of swimming technique assess your form. Swimming is a highly intricate and complex motion. There are myriad potential breakdown points. Having a qualified expert assess your form may prevent injury, and is absolutely essential when recovering from an injury.

Very common mistakes to look out for include:

- Crossing Mid-Line – with proper trunk rotation and arm position, the hand should not be reaching across the midline of the body while entering the water.

- Entering the water in a ‘thumb down’ position (with palm facing outward). This increases impingement along the top of the shoulder. The correct technique is to externally rotate the arms during the over-water recovery (palms facing the water) and not begin to internally rotate until after the ‘early entry phase’ greater tubercle has cleared the acromion process.)

- Unilateral breathing or rolling too far during the breath can be a problem as the shoulder on the opposite side to the breath is placed in a compromised position.

Research has demonstrated that swimmers will adapt their form naturally to accommodate pain. Some of these changes away from the ‘ideal’ stroke, are adaptive! The swimmers coach or rehab specialist should not attempt to force the swimmer out of these natural compensations until the tissue pathology has recovered and the strength and conditioning of the athlete will allow for ‘proper’ form. 6 7

| Let’s break down front crawl or ‘freestyle’ as this is the stroke that makes up ~ 80% of training volume for the average competitive swimmer. 8 The pull-through is where propulsion is achieved and is further divided into different phases consisting of the hand entry, the catch, mid-pull, and finish or end pull-through. During the pull- through phase, the scapula is protracted while the humerus is adducted, extended, and internally rotated. Stroke power is achieved through the shoulder adductors, extenders, and internal rotators with the serratus anterior and latissumus dorsi being the key propulsion muscles for swimmers. Because the trunk is rotated away from the side that is beginning to pull, the shoulder avoids a true impingement position of forward flexion with internal rotation and horizontal adduction. Swimmers subject their shoulders to Glenohumeral impingement for up to 25% of the stroke, even with proper form! 9[ppmaccordion][ppmtoggle title=”Other Strokes – Read More“]Butterfly has a similar motion at the shoulder as freestyle, but the stresses are different because both arms are moved through the same motion simultaneously rather than alternating. For this reason, no trunk rotation occurs and the shoulder spends more time in an impingement position. The mobility demands of the entire Upper Quarter are increased (especially the scapulothoracic articulation and the Thoracic spine). Last, much of the propulsion during the butterfly comes from the hips and trunk.; so, any inefficiency of these muscle groups can lead to increased stress on the shoulders and must be resolved.Tovin 2006The backstroke is opposite to the freestyle stroke with the shoulder in retraction, horizontal abduction, and external rotation at hand entry and the beginning of pull-through. This position is less strenuous in some ways, but will increase stress on the anterior capsule. Efficient trunk roll and scapulothoracic mobility is essential. Tovin 2006

Movement at the shoulder during breaststroke can vary, with more motion occurring below the surface of the water than any other stroke. Unlike the other strokes, the hands never move below the hips so the tensile forces on the rotator cuff that occurs during the other strokes at the end of pull-thorough do not occur during breaststroke. Tovin 2006[/ppmtoggle] [/ppmaccordion] |

What you can do right away if you’re experiencing Symptoms

Lower your volume or stop completely depending on the severity of symptoms. Avoid swimming fatigued. Poor endurance, rapid ramping up of volume/intensity and swimming fatigued will feed the cycle. 10 11

- Stop using hand paddles.

- Consider the temporary use of fins.

- Avoid the prolonged use of kickboards. If you must do kicking sets, grab the sides of the board (not the top) or use no kick board (go hands to sides).

- Avoid Butterfly. Consider increasing Breatstroke use.

- Address obvious postural distortions. A scapula in the correct position makes it much less of a strain to raise the arms….

- Attempt to self-analyze form (e.g. Are you keeping head high for some reason? Are you striding out too far? etc)

- Warm up well.

Swimmers Shoulder is an injury that can be prevented or reduced with proper pre-season conditioning (Tovin 2006). In any sport with a specific injury rate as high as 40 > 91%, screening and injury prevention training should be uniformly adopted.

We highly encourage all swimmers out there to seek out a qualified profession to

1) Identify and correct muscle imbalances and postural distortions; 2) Ensure proper conditioning for RTC and keep scapular positioning muscles; 3) Identify training errors; 4) Identify inefficiencies in stroke mechanics.

Contact Us to schedule an evaluation with one of our Sports Physical Therapists today.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!