Ankle Sprains

Ankle sprains are one of the most common athletic injuries. It’s estimated that ankle injuries account for 10-34% of ALL athletic injuries, with 80% of those ankle injuries being classified as lateral ankle sprains. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sports that rely on quick change of directions, frequent jumping and landing, and powerful acceleration and deceleration such as basketball, soccer, and football have the highest incidence of ankle sprains. 8 9

Anatomy Background

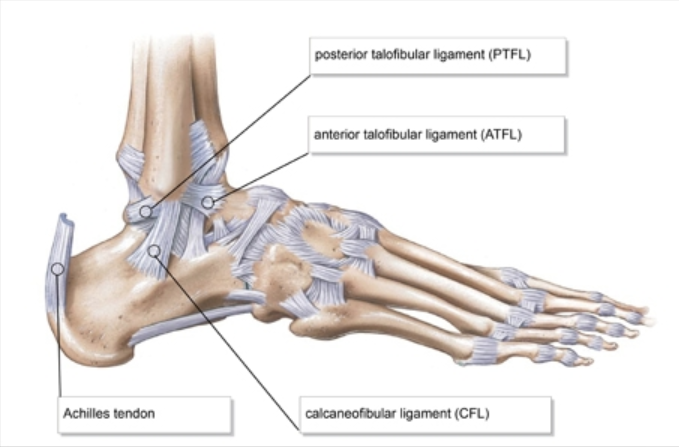

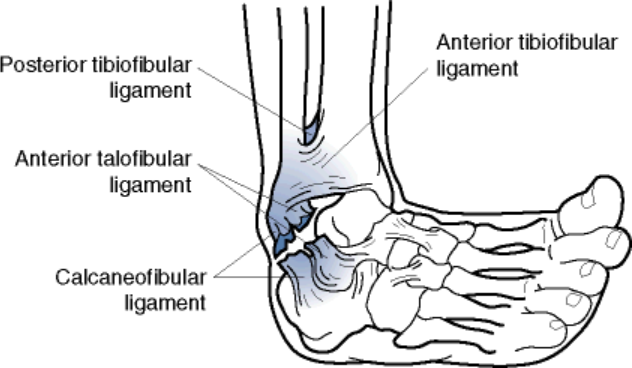

Joint structure, the surrounding muscles and tendons, and the ligaments of the ankle provide the joint with the necessary support to be able to meet the intense demands of one’s given sport. The major ligaments of the lateral aspect (outside) of the ankle include the anterior talo-fibular ligament, the calcaneofibular ligament, and posterior talfibular ligament. 10

These ligaments are stressed when the ankle is in a position of plantarflexion and inversion (think toes pointed and turned in) with even more stress being put on these ligaments when load is involved. Athletically we see this with jumping and landing (especially if you land on an opposing players foot!) or with planting and pushing off to make a quick cut. 11 12 13 We also see this happen with hikers and trail runners when they step on an uneven surface like a rock, root, or depression in the ground that results in them rolling onto the outside of their foot/ankle.. We’ve also seen it happen in every day like just stepping in a hole in the ground, or misstepping as you come down the stairs! It’s this quick and forceful stretch (and in some cases tearing!) of these ligaments that is distinctive of a lateral ankle sprain.

*There are ligaments on the medial aspect (inside) of the ankle including the deltoid and anterior tibiofibular ligament, however given the anatomy of the ankle joint, it is not common for these ligaments to stressed with traditional ankle sprains.

A sprained ankle can be identified by the following 14

- This combined plantarflexion and inversion mechanism of injury where the athlete reports “rolling” onto the outside of his foot

- Pain on the lateral aspect of ankle and/or the outside of his foot

- Swelling on the outside of the foot/ankle

- Bruising on the outside of the foot/ankle

- Difficulty putting full weight through the injured ankle

How is it Graded?

Ankle sprains are graded on a scale of Grade I-Grade III. There are a few different grading criteria systems that are used with some focusing on the extent of the injury to a single ligament, while others focus on the number of ligaments that involved in the sprain. In general realize that a Grade I sprain is the least severe and typically shows very little if any swelling and little to no difficulty walking on the injured ankle. A Grade II sprain will show moderate swelling and perhaps some bruising or discoloration, some loss of motion, point tenderness, and pain with weightbearing and walking. A Grade III sprain is the most severe ankle sprain and will have significant swelling and bruising on the outside of the ankle and into the foot, limited range of motion, pain to touch, and significant pain with bearing weight and putting weight through the ankle. 15 16

| American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons 17 | International Classification of Functioning 18 | |

| Grade I | Partial Tearing- Mild tenderness and swelling, ability to walk with minimal pain, no mechanical instability with clinical stress testing | No ligamentous laxity, minimal loss of ankle motion(less than 5 degrees), minimal swelling, no loss of function |

| Grade II | Incomplete Tear of Ligament with moderate functional impairment- Moderate pain and swelling, some loss of motion, pain with weightbearing, Mild to moderate instability with clinical stress testing | Clinical testing shows involvement of Anterior taolofibular ligament without injury to the calcaneofibular ligament. Total loss of ankle motion between 5-10 degrees, some loss of function |

| Grade III | Complete Tearing and Loss of integrity of a Ligament. Severe swelling and pain, unable to bear weight on the ankle, Instability is noted with clinical stress testing | Clinical testing shows involvement of both the talofibular and calcaneofibular ligament. Total loss of ankle motion greater than 10 degrees, near total loss of function |

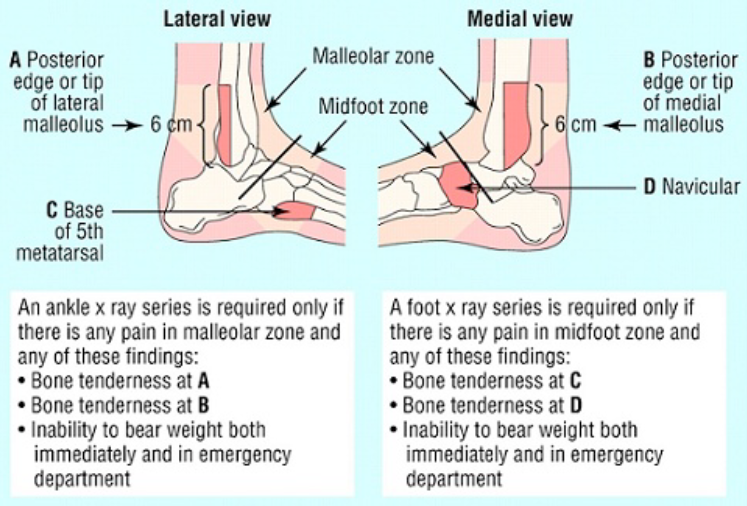

*It should be noted that for more severe sprains it can be very difficult to tell the difference between an ankle sprain and an ankle fracture. For this reason we follow the Ottawa Ankle Rules to determine the need for an x-ray. If there is pain to touch the bones of the ankle (shown below as the malleolar and midfoot zones) and an inability to bear weight immediately after the injury it is best to follow up with your medical provider to rule out a fracture. 19 20

* It is important to note that these ‘rules’ are very useful in avoiding unnecessary x-rays in the mature population. However, kids present uniquely and this protocol has not been shown to be as useful in the pediatric population. Thus, at times, a bit of extra caution is warranted.

What to Do?

A comprehensive and complete rehab is important following an ankle sprain. We’ll break the rehab into two phases.

Acute Phase

The focus of this phase is on protecting the injury as to not make it worse, controlling swelling, and gradually returning to a normal gait pattern. Traditionally we focused on “RICE”- which involved Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation as a way to promote healing. We know this to strategy to be successful for helping to control pain, and minimizing swelling and limiting secondary injury on a cellular level. However, more recently there’s been a push to clarify that the “rest” should really be explained as “Optimal Loads”- meaning we should encourage use and motion of the injury as much as we can- but careful not add too much stress to soon. We’re shooting for the “sweet spot” that facilitate healing, while encouraging early mobility. As such, there’s a push for a new acronym, POLICE– Protect, Optimal Loads, Ice, Compression, Elevation. The “Optimal Load” will vary based on the severity of the injury. For some this may involve bracing or use of crutches initially with a gradual return to full weight bearing. Regardless of what your beginning “optimal load” is- the research is unanimous that early mobilization and weightbearing is the key to the initial phase of rehab- and those who began rehab while still in the acute phase had a decrease in ankle sprain recurrences measured at 1 year after the original injury!

One of the benefits of having your ankle sprain evaluated by a sports physical therapist is their understanding of what your optimal load should be. Given that current research on the rehabilitation of ankle sprains strongly supports the POLICE strategy- this will put you on the right path to a full recovery as quickly as possible.

Other components of the acute phase will focus on restoring normal range of motion at the ankle, helping to minimize swelling through different manual therapy and massage techniques as well as taping, and a beginning to strengthen the ankle with specific exercises. Research has shown that a significant decrease in recurrence rate was observed for those who initiated rehab while still in the acute phase. 21 There is no reason to wait!

Progressive Loading and Sensorimotor Training Phase

The next stage of rehab is the progressive loading and sensorimotor training phase. While continuing to restore full ROM with manual therapy techniques including joint mobilizations- there is a shift to more weight bearing exercises especially with a focus on single leg balancing activities. 22 So much of our sports involve being able to be strong on one leg (think being able to plant and change direction on a court, jump and land off of one leg going up for a lay up or rebound, or even just planting a foot when running and being able to go through a normal gait sequence) that is important to regain this functional stability and normal proprioception of the ankle.

| *Proprioception is defined as “the ability to take sensory information from the environment and integrate that information to create a motor response”. 23 In the case of a sprained ankle- it is your body’s ability to detect information about the position of your ankle joint and instantaneously relay information to your pain so that the muscles of your lower leg can react and contract to help stabilize the joint. 24 Proprioception training has been shown to not only help restore normal ankle function25 – but have also shown to be effective in decreasing the risk of future ankle sprains- regardless of ankle sprain history! 26 27 If you are someone with a history of ankle sprains- get going on an appropriate balance/proprioception program as this can help reduce the risk for future injuries! |

This stage is important- and it’s important to complete! Research is unanimous in its support for exercise and proprioception training and has been shown to decrease the risk of recurrence of ankle sprains- BUT it takes a high volume of training. It’s suggested that greater than 900 combined minutes of training is needed to maximize the effect. That’s a combined 15 hours of training! (2-3 hrs of training per/week over 5-8 weeks!) 28

In addition to addressing the muscles surrounding the ankle, it may also be beneficial to address muscles at the hip- specifically the glute medius. A study performed on male soccer players showed that decreased strength of the glute medius muscle increased the risk of non-contact ankle sprains. 29

Prevention

Can these injuries be prevented in the first place? Yes! There is strong research that shows a pre-season training program that focuses on proprioceptive training can help to prevent ankle sprains, and this is especially true for those who have sprained an ankle previously! These programs are relatively simple, with minimal equipment needed, and can be as little 5 minutes a day. It’s easy to work into a traditional “warm up” routine. 30

Bracing

Bracing may also be a good option- especially if this is an injury that occurs during the season and you are trying to return to play as quickly as possible. Bracing has been shown to multiple sources to be effective in decreasing the risk of ankle sprains – especially for those how have suffered a previous ankle sprain- while most studies show no ill effects on your speed or agility while in the brace. 31 Most agree that a lace up brace is the best options compared to more of a neoprene or semi-rigid brace and it’s recommended that in addition to a full rehab- one should wear a brace with “high risk” activities (sports) for up to 1 year. 32

Do you need surgery?

Probably not. There is good evidence to show nearly all people will have success with the right combination of ROM, strength, and balance/proprioception training and the professional consensus is that this should always be tried first!

For as common as ankle sprains are- it’s imperative that they get the right treatment! Avoid old-school outdated approaches like ultrasound, which may have traditionally been thought of to help rehab, but more recent research shows it has virtually no impact on the rehab! Also – make sure you are doing more than just ankle strengthening exercises- it is important to restore the dynamic stability of the ankle, especially with sports specific movements like quick cutting, jumping, and landing drills and this only happen with exercises that target these properties – not just strengthening and stretching. 33

The strongest evidence shows that by taking a systemized approach that focuses on controlling swelling, restoring full ankle motion and strength, and restoring normal proprioception, and progressing to more functional strengthening including addressing any hip weakness is the best way to get you back in the game as fast as possible! 34 35

- Martin, R. L., Davenport, T. E., Paulseth, S., Wukich, D. K., Godges, J. J., Altman, R. D., … & MacDermid, J. (2013). Ankle stability and movement coordination impairments: ankle ligament sprains: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability and health from the orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 43(9), A1-A40.

- Wolfe, M. W. (2001). Management of ankle sprains. American family physician, 63(1).

- Gribble, P. A., Bleakley, C. M., Caulfield, B. M., Docherty, C. L., Fourchet, F., Fong, D. T. P., … & Refshauge, K. M. (2016). 2016 consensus statement of the International Ankle Consortium: prevalence, impact and long-term consequences of lateral ankle sprains. Br J Sports Med, bjsports-2016.

- Schiftan, G. S., Ross, L. A., & Hahne, A. J. (2015). The effectiveness of proprioceptive training in preventing ankle sprains in sporting populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of science and medicine in sport, 18(3), 238-244.

- van Ochten, J. M., van Middelkoop, M., Meuffels, D., & Bierma-Zeinstra, S. M. (2014). Chronic complaints after ankle sprains: a systematic review on effectiveness of treatments. Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy, 44(11), 862-C23.

- Powers, C. M., Ghoddosi, N., Straub, R. K., & Khayambashi, K. (2017). Hip Strength as a Predictor of Ankle Sprains in Male Soccer Players: A Prospective Study. Journal of athletic training, 52(11), 1048-1055.

- Gross, M. T., & Liu, H. Y. (2003). The role of ankle bracing for prevention of ankle sprain injuries. Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy, 33(10), 572-577.

- Martin, R. L., Davenport, T. E., Paulseth, S., Wukich, D. K., Godges, J. J., Altman, R. D., … & MacDermid, J. (2013). Ankle stability and movement coordination impairments: ankle ligament sprains: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability and health from the orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 43(9), A1-A40.

- Schiftan, G. S., Ross, L. A., & Hahne, A. J. (2015). The effectiveness of proprioceptive training in preventing ankle sprains in sporting populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of science and medicine in sport, 18(3), 238-244.

- Wolfe, M. W. (2001). Management of ankle sprains. American family physician, 63(1).

- Martin, R. L., Davenport, T. E., Paulseth, S., Wukich, D. K., Godges, J. J., Altman, R. D., … & MacDermid, J. (2013). Ankle stability and movement coordination impairments: ankle ligament sprains: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability and health from the orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 43(9), A1-A40.

- Wolfe, M. W. (2001). Management of ankle sprains. American family physician, 63(1).

- Powers, C. M., Ghoddosi, N., Straub, R. K., & Khayambashi, K. (2017). Hip Strength as a Predictor of Ankle Sprains in Male Soccer Players: A Prospective Study. Journal of athletic training, 52(11), 1048-1055.

- Wolfe, M. W. (2001). Management of ankle sprains. American family physician, 63(1).

- Martin, R. L., Davenport, T. E., Paulseth, S., Wukich, D. K., Godges, J. J., Altman, R. D., … & MacDermid, J. (2013). Ankle stability and movement coordination impairments: ankle ligament sprains: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability and health from the orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 43(9), A1-A40.

- Wolfe, M. W. (2001). Management of ankle sprains. American family physician, 63(1).

- Wolfe, M. W. (2001). Management of ankle sprains. American family physician, 63(1).

- Martin, R. L., Davenport, T. E., Paulseth, S., Wukich, D. K., Godges, J. J., Altman, R. D., … & MacDermid, J. (2013). Ankle stability and movement coordination impairments: ankle ligament sprains: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability and health from the orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 43(9), A1-A40.

- Martin, R. L., Davenport, T. E., Paulseth, S., Wukich, D. K., Godges, J. J., Altman, R. D., … & MacDermid, J. (2013). Ankle stability and movement coordination impairments: ankle ligament sprains: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability and health from the orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 43(9), A1-A40.

- Wolfe, M. W. (2001). Management of ankle sprains. American family physician, 63(1).

- Holme, E., Magnusson, S. P., Becher, K., Bieler, T., Aagaard, P., & Kjaer, M. (1999). The effect of supervised rehabilitation on strength, postural sway, position sense and re‐injury risk after acute ankle ligament sprain. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 9(2), 104-109.

- Martin, R. L., Davenport, T. E., Paulseth, S., Wukich, D. K., Godges, J. J., Altman, R. D., … & MacDermid, J. (2013). Ankle stability and movement coordination impairments: ankle ligament sprains: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability and health from the orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 43(9), A1-A40.

- Rivera, M. J., Winkelmann, Z. K., Powden, C. J., & Games, K. E. (2017). Proprioceptive Training for the Prevention of Ankle Sprains: An Evidence-Based Review. Journal of athletic training, 52(11), 1065-1067.

- Schiftan, G. S., Ross, L. A., & Hahne, A. J. (2015). The effectiveness of proprioceptive training in preventing ankle sprains in sporting populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of science and medicine in sport, 18(3), 238-244.

- Martin, R. L., Davenport, T. E., Paulseth, S., Wukich, D. K., Godges, J. J., Altman, R. D., … & MacDermid, J. (2013). Ankle stability and movement coordination impairments: ankle ligament sprains: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability and health from the orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 43(9), A1-A40.

- Schiftan, G. S., Ross, L. A., & Hahne, A. J. (2015). The effectiveness of proprioceptive training in preventing ankle sprains in sporting populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of science and medicine in sport, 18(3), 238-244.

- Rivera, M. J., Winkelmann, Z. K., Powden, C. J., & Games, K. E. (2017). Proprioceptive Training for the Prevention of Ankle Sprains: An Evidence-Based Review. Journal of athletic training, 52(11), 1065-1067

- Doherty, C., Bleakley, C., Delahunt, E., & Holden, S. (2017). Treatment and prevention of acute and recurrent ankle sprain: an overview of systematic reviews with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med, 51(2), 113-125.

- Powers, C. M., Ghoddosi, N., Straub, R. K., & Khayambashi, K. (2017). Hip Strength as a Predictor of Ankle Sprains in Male Soccer Players: A Prospective Study. Journal of athletic training, 52(11), 1048-1055.

- Schiftan, G. S., Ross, L. A., & Hahne, A. J. (2015). The effectiveness of proprioceptive training in preventing ankle sprains in sporting populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of science and medicine in sport, 18(3), 238-244.

- Gross, M. T., & Liu, H. Y. (2003). The role of ankle bracing for prevention of ankle sprain injuries. Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy, 33(10), 572-577.

- Gribble, P. A., Bleakley, C. M., Caulfield, B. M., Docherty, C. L., Fourchet, F., Fong, D. T. P., … & Refshauge, K. M. (2016). 2016 consensus statement of the International Ankle Consortium: prevalence, impact and long-term consequences of lateral ankle sprains. Br J Sports Med, bjsports-2016.

- Martin, R. L., Davenport, T. E., Paulseth, S., Wukich, D. K., Godges, J. J., Altman, R. D., … & MacDermid, J. (2013). Ankle stability and movement coordination impairments: ankle ligament sprains: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability and health from the orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 43(9), A1-A40.

- Martin, R. L., Davenport, T. E., Paulseth, S., Wukich, D. K., Godges, J. J., Altman, R. D., … & MacDermid, J. (2013). Ankle stability and movement coordination impairments: ankle ligament sprains: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability and health from the orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 43(9), A1-A40.

- Powers, C. M., Ghoddosi, N., Straub, R. K., & Khayambashi, K. (2017). Hip Strength as a Predictor of Ankle Sprains in Male Soccer Players: A Prospective Study. Journal of athletic training, 52(11), 1048-1055.