PATELLOFEMORAL PAIN SYNDROME (PFPS)

What is it

Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) is the most common cause of knee pain. 1 in 4 people are likely to develop Patellofemoral pain at some point in their lives – and this number goes up among athletes and active teenagers.

Women more than men.

It is the most common single diagnosis among runners and in sports medicine centers. 1

70% to 90% of individuals with PFPS have recurrent or chronic pain; and, recent research suggests that having PFPS as a younger individual may predispose one to develop patellofemoral osteoarthritis later in life. 2

How is it Diagnosed

X-rays are typically unnecessary as a particular set of clinical findings can confirm a diagnosis of PFPS. 3 Your orthopedist or PCP may order advanced imaging to visualize the extent of wear or to rule out other potential diagnoses.

What is Patellofemoral Pain?

PFPS is a description of the pain’s location – Under or around the knee cap (or patella). A Diagnosis of PFPS does not tell us the cause of the pain – it simply tells us that the source of the pain is in the front of the knee, in and around the kneecap (or patella).

What You May Experience:

- Pain is variable depending on activity level and typically decreases with rest

- Pain is often worst with walking up or down stairs

- Pain associated with sitting for long periods of time with the knee bent (the so-called ‘movie theater sign’) 4

- ”Cracking”, “Grinding” or “Popping” when you bend or straighten your knee

PFPS has many causes and can present differently depending on the combinations of precise tissues that are irritated.

For this reason, a Diagnosis of PFPS is often ‘Sub-Classified’.

For those interested in details, see the box below.

For those looking for the cliffs notes, skip box.

| Subclassification of PFPS 5

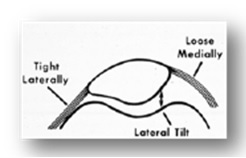

– Compressive Syndromes – Excessive Lateral Pressure Syndrome (ELPS) – This Subclassification describes a patient with an imbalance of the tissues inserting on the knee cap. Typically, lateral (outside) structures are excessively taught causing the patella to tilt or shift to the side. This may place unequal pressure, increasing compression and/or ‘grinding’ on the outside of the joint, and an increased stretch-strain to the tissues supporting the medial (inside) of the joint. – Global Patellar Pressure Syndrome (GPPS) – Associated with more global or diffuse stiffness, the knee cap becomes excessively compressed into the thigh bone. This is most common post-operatively if the patient was immobilized for a prolonged period of time (or with improper early rehab intervention). – Patellar Instability – This is the opposite end of the spectrum from the ‘compressive’ syndromes. Instability can result from congenital (‘born with it’) conditions or acute injuries resulting in a dislocation of the patella and a disruption of the ‘anchoring’ tissues. – Biomechanical Dysfunction – It serves our purpose to think of the knee as a simple ‘hinge’ joint. Just like the hinges on a door, they operate smoothly in one direction. However, if the door is not hung properly, the hinges will start to malfunction in time. Similarly, the knee functions best when the leg is kept in proper alignment. If there is weakness and/or poor control present above the knee (in the hip/pelvic/core) or below the knee (foot/ankle), the knee often ‘pays the price’. The hinge joint is subjected to side-to-side and/or rotational stresses, and begins to break down. * Especially in our youth athletes – this is often the primary issue underlying the Patellofemoral pain In contract to the ‘Excessive Lateral Pressure Syndrome’ (ELPS), where the patella is being drawn or pulled laterally on the thigh bone (femur), what we commonly see in this case is that the femur is moving out from under the knee cap. In other words, the train is NOT running off the tracks… Rather, the tracks are moving out from underneath the train. Take a look at the MRI below.

The image on top demonstrates a patient with ELPS. In non-weight bearing, with the thigh straight, when they fire their quadriceps muscle we can clearly see the patella ’tracking’ laterally and compressing along the lateral facet. The bottom image is of a person with ‘Biomechanics Dysfunction’ performing a ‘Step Down’ maneuver. Take note, the patella remains mid-line – however, the patient has poor control of their femur (typically associated with poor hip/pelvic strength and/or neuromuscular control). The thigh bone has ‘knocked in’ and rotated medially. The result is shearing and lateral compression stress to the articulation between the knee cap and the thigh bone. In this case, the track has clear moved from under the train.

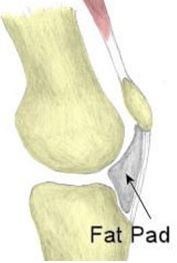

– Direct Patellar Trauma – Just like it sounds. This can include bone bruises, articular cartilage lesions or even fracture. – Soft Tissue Lesions – As mentioned previously, often the source of pain may include ‘soft’ tissues (not bone) adjacent to the kneecap. Common examples include: –The Suprapatellar Plica – A Fold, or ridge in the tissue that encapsulates the knee can become inflamed. This can lead to pain and snapping sensation with movement. (http://www.moveforwardpt.com/symptomsconditionsdetail.aspx?cid=65631f95-04b3-41f7-b7dc-402467cdbaa0) – The Medial Patellofemoral Ligament – The guy-wire that stabilizes the patella against excessive lateral movement. Can be injured traumatically, or irritated with repetitive stress. (http://www.moveforwardpt.com/symptomsconditionsdetail.aspx?cid=f1a75188-3098-4710-a0d5-82a369603ea6) – Patellar Fat Pad – The ‘padding’ underlying the patellar tendon, is present to prevent this important tendon from rubbing/fraying against the underlying bone. It is highly innervated (very painful when damaged) and can become swollen and impinged. – Illiotibial Band – The Illiotibial Band (ITB) irritability is often thought of as a separate ‘issue.’ However, it is common for an athlete to suffer PFPS and ITB pain simultaneously as the two diagnoses share many common etiologies. * Click here for much more information on Iliotibial Band Syndrome – Overuse Injuries – Especially in the youth athlete, a degree of ‘overuse;’ may underlie the development of PFPS. With ‘overuse’ as the primary driving factor, we also often see a concomitant diagnosis such as Patellar Tendonitis (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patellar_tendinitis) or growth plate injuries (Traction Apophysitis), the most common being Osgood-Schlatters Disease (http://www.moveforwardpt.com/symptomsconditionsdetail.aspx?cid=48921dd7-f607-47fc-aa76-7fa034815fc8) |

What Causes It?

PFPS is a “repetitive stress syndrome “. It is the most common overuse injury of the lower extremity. 6

Ultimately, it is associated with poor patellar alignment, friction between the under surface of the patella and the femur, and strain to the tissues that attach to the patella.

Common contributing factors include:

- Weakness, tightness, or stiffness in the muscles around the hip & knee

- Abnormalities in lower leg alignment

If you are a youth athlete, your Patellofemoral pain may be a result of a softening of the cartilage under the patella, or an inflammation of the soft tissues surrounding the kneecap.

Conversely, if you are an aging athlete, you are more likely to experience a wearing out of the cartilage under the patella.

Note – this may sound discouraging, but you may still respond very well to a comprehensive rehabilitation program. If you have recently been diagnosed with ‘mild’ or ‘moderate’ ‘degenerative’ wear of the patellar cartilage (or ‘Chondromalacia’), take heart – the cartilage behind the knee cap is the thickest piece of cartilage in the human body, and ‘wearing’ down is, to some degree, a normal process. Furthermore, the extent of degeneration often does not correlate well to the severity of symptoms. In fact, in many cases, the cartilage behind the kneecap may not be responsible for the symptoms of anterior knee pain at all. Click here to read a fascinating story that highlights this very phenomenon. The lead researcher performed arthroscopic surgery on his own knee! The goal was to provide a description of the quality and severity of pain associated with probing various tissues in and around the knee.

|

Patellofemoral pain commonly ‘flares up’ with a sudden increase in activity. This can be related to youth athletics seasonal fluctuations, a conscious increase in exercise, or a change in job that requires more squatting or stairs. While the knee is naturally fairly resilient, once the tissues in the front of the knee are flared up, you may experience frequent pain and difficulty completing even the simplest daily tasks.

Basically, tasks that place the Patellofemoral joint under the highest compressive loads are most likely to bring on PFPS. These include:

– Squatting — 7 x Bodyweight (Deep Squatting = up to 20 x Bodyweight!)

– Descending Stairs — 5 x Bodyweight

– Running — 7 x Bodyweight

* Biking is not excessively ‘compressive’ (loads of only 50% body weight while on a bike) BUT the very high number of repetitions can make up for these relatively low loads / cycle. ‘Fat Pad’ Impingement and Lateral Compression Syndrome are likely to be exacerbated by biking. Unlike many other forms of knee pain, cycling may not be a ‘good’ form of exercise when in an acute flare up.

————————————————————————————————————

What you can do

Adhere to some basic advice

– Avoid sitting with knees in a deep knee bend for long periods.

– Minimize Stairs, Squatting and other tasks that place large compressive loads across the knee cap.

– Ice the front of the knee after heavy activity or when otherwise ‘flared up’.

Seek the services of a Physical Therapist that specializes in Sports or Orthopedics!

———————————————————————————————————-

Physical Therapy for PFPS

Your Physical Therapist will evaluate the knee in detail. They will also evaluate the hip and ankle for faulty alignment, stiffness or weakness that can increase strain to the knee. Your PT should also evaluate your movement patterns. This will likely include watching you walk, run (if applicable), Squat, Step up/down, etc.

After a comprehensive evaluation, your therapist will prescribe a rehabilitation program specific to your ‘sub-type’ and your particular areas of impairment.

Your program may include:

– Targeted strengthening and/or stretching exercises.

– Movement ‘re-education’ exercises to develop dynamic control of the lower limb and protect the knee joint during activity/sport.

– Patellar Taping or Bracing if indicated during activity.

– Assessment of foot alignment to determine the need for a custom foot orthosis.

– Teach proper management strategies to prevent the return of pain.

Your physical therapist will work with you to help you stay active and maintain your fitness level. You may need to modify your activity level or change your training activities until you recover; your therapist will show you how to do activities and exercises that will not increase your pain.

| Baltimore MD In 2009 – An International Research Retreat of acknowledged experts in the fields of rehabilitative medicine with special interest in PFPS. The purpose of this retreat was to share and deliberate on current research, and summarize current best practices for 1) Identifying factors related to development of PFPS and 2) Evidence based treatment for PFPS.This is a fabulous summary of what we know, what we think, and what questions remain.

Full Summary of this retreat is linked here. |

An abundance of evidence from high quality randomized clinical trials or systematic reviews support the short-term effect on PFPS. 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 These include exercise therapy, 14 15 16 17 patellar taping, 18 foot orthoses, 19 and multimodal physiotherapy approaches. 20 21 22 23 24

PFPS is much easier to treat if it is caught early. Report the first signs of knee pain to your physical therapist.

| While treatment for PFPS may be successful for the short-term, long-term results are less promising. In a recent prospective study, it was reported that, 5 years following completion of a rehabilitation program for PFPS, 80% of individuals still reported pain and 74% had reduced their physical activity level. 25I would suggest that many of these subjects were not treated “optimally” – Early and Aggressively! |

There is strong consensus among sports medicine professionals that an aggressive and prolonged course of rehab is likely the best approach for PFP. “(L)onger-term benefits may require sustained treatment regimens (beyond the 6-8 treatments routinely employed)”. 26

If you are experiencing early signs of PFP, or if it is already limiting your activity level, get help!

Click here to request an appointment with one of our sports physical therapists today.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!