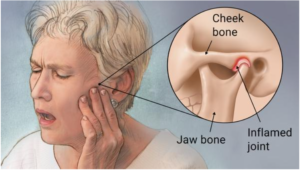

Nearly 33% of the general population experience persistent jaw pain.1 The joint that makes up your jaw, and allows you to open and close your mouth is referred to as the temporomandibular joint (TMJ).2 Pain and dysfunction of the joint is referred to as temporomandibular dysfunction (TMD). People often refer to TMD as TMJ, but this is incorrect. TMJ is referencing the joint itself, while TMD is referencing the dysfunction of the joint.3

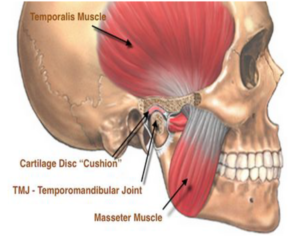

The temporomandibular joint consists of your cheekbone (mandible), and the temporal bone of your skull.4 Between these two bones is an articular disc. This disc comes from connective tissues that surround the joint between your skull and cheekbone. As you open your mouth, the disc moves forward, and backwards as you close your mouth. The movement of the disc, although subtle, is meant to decrease the friction between the two bones that make up your jaw.5

Temporomandibular joint dysfunction can be a collection of symptoms, including but not limited to:

- Pain while eating or talking

- Headache

- Tinnitus

- Limited ability to open and close your mouth6

Like pulling a muscle in your back or leg, the muscles in the face can get injured as well. Symptoms of TMD may be of muscular origin, or it could also be the actual joint itself.7 Clicking, locking, or popping when opening and closing your mouth is one of the common indicators that jaw pain may be due to an intra-articular problem. This phenomenon may or may not be audible, and is usually felt in front of the ear, and radiate down your jaw. The source of the clicking is often due to an imbalance of movement of the articular disc as a person opens and closes their mouth.8

Movement imbalances may be caused due to tissues that are tight such as the connective tissue surrounding a joint.9 Muscles that are weak, and unable to fully contribute to movement are also sources of movement imbalances. A physical therapist has the knowledge and skills to evaluate and treat imbalance movements associated with TMD. Throughout their formal education, physical therapists learn the muscles, bones, nerves and ligaments in the human body, and the face is no exception.

Your therapist will want to conduct a formal examination to assess the presence of TMD, and exclude more sinister conditions.10 They may watch you perform several movements of the head and neck. They will then look closer at the movement of your jaw, and measure how far you can open your mouth, as well as how far you can move your jaw forward, and to both sides. During your initial examination and the treatment sessions following, your therapist may need to feel the muscles of your jaw from inside your mouth. Your therapist will wear gloves just like your dentist, and may mobilize different muscles, or even the TMJ itself.

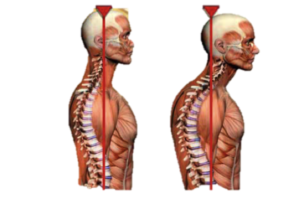

If a muscle of the face or jaw, or the joint capsule itself is restricted, movement of the articular disc may be affected. 11 The therapist will use soft-tissue mobilization by using their hands to gently knead the restricted tissues. 12 The therapist might also mobilize the joint itself, providing a stretch to the joint capsule to ensure neither muscle nor connective tissues are causing any restriction. 13 Neck pain is a common co-occurrence with TMD due to the close proximity of muscle attachment points.14. The muscles in your neck may be lengthened or shortened due to a person’s habitual posture.15 Posture varies from person to person. Ideally, the canal of your ear lines up with the middle of your shoulder. Restrictions in the tissues to the neck may create what is referred to as forward-head posture, which may in turn alter the mechanics of opening and closing your mouth.16 Your physical therapist might perform manual therapy techniques on structures in your neck, to ensure there are no restrictions causing an altered head position.

Alterations in the length of muscles of the neck may also warrant the use of a specialized treatment known as trigger point dry needling.17 The PT will identify a taut band of muscle tissue known as a “trigger point” or “knot” and insert a needle in its proximity. The mechanical stimulus initiates a reaction from the central nervous system that helps the muscle relax, and return to its original length and position.

Your therapist may also educate you on the importance of reducing stress.18 Oftentimes, TMD may be brought on by grinding teeth due to increased stress levels.19 Together, you and your therapist will come up with strategies to better manage your stress, and hopefully reduce the tendency to grind your teeth.

The physical therapist might also provide therapeutic exercises to have you stretch muscles that are tight, and strengthen those that are weak.20 Your PT may also provide you with a home exercise program so you can continue to make improvement on your own. You and your therapist will work as a team to identify solutions that work best to decrease your pain, and help you return to eating, sleeping, and speaking without discomfort.

Experience the VASTA Difference – Request an appt. or call us today to get started immediately. 802-399-2244.

- Reneker J, Paz J, Petrosino C, Cook C. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests and signs of temporomandibular joint disorders: A systematic review of the literature. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41(6): 408-416. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2011.3644

- Neumann D. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System Foundations for Rehabilitation. Third ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2017

- Neumann D. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System Foundations for Rehabilitation. Third ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2017

- Neumann D. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System Foundations for Rehabilitation. Third ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2017

- Neumann D. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System Foundations for Rehabilitation. Third ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2017

- Harrison AL, Thorp JN, Ritzline PD. A proposed diagnostic classification of patients with temporomandibular disorders: Implications for physical therapists. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014;44(3):182-197. doi:10.2519/jospt.2014.4847

- Harrison AL, Thorp JN, Ritzline PD. A proposed diagnostic classification of patients with temporomandibular disorders: Implications for physical therapists. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014;44(3):182-197. doi:10.2519/jospt.2014.4847

- Harrison AL, Thorp JN, Ritzline PD. A proposed diagnostic classification of patients with temporomandibular disorders: Implications for physical therapists. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014;44(3):182-197. doi:10.2519/jospt.2014.4847

- Neumann D. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System Foundations for Rehabilitation. Third ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2017.

- Wright EF, North SL. Management and treatment of temporomandibular disorders: A clinical perspective. J Man Manip Ther. 2009;17(4):247-254. doi:10.1179/106698109791352184

- Neumann D. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System Foundations for Rehabilitation. Third ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2017.

- Furto ES, Cleland JA, Whitman JM, Olson KA. Manual physical therapy interventions and exercise for patients with temporomandibular disorders. CRANIO®. 2006;24(4):283-291. doi:10.1179/crn.2006.044

- Furto ES, Cleland JA, Whitman JM, Olson KA. Manual physical therapy interventions and exercise for patients with temporomandibular disorders. CRANIO®. 2006;24(4):283-291. doi:10.1179/crn.2006.044

- Calixtre LB, Oliveira AB, de Sena Rosa LR, Armijo-Olivo S, Visscher CM, Alburquerque-Sendín F. Effectiveness of mobilisation of the upper cervical region and craniocervical flexor training on orofacial pain, mandibular function and headache in women with TMD. A randomised, controlled trial. J Oral Rehabil. 2019;46(2):109-119. doi:10.1111/joor.12733

- Neumann D. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System Foundations for Rehabilitation. Third ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2017.

- Neumann D. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System Foundations for Rehabilitation. Third ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2017.

- Teken L, Akarsu S, Durmus O, Cakar E, Dincer U, Kiralp M. The effect of dry needling in the treatment of myofascial pain syndrome: a randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Rheumatology. 2013;3(32):309-315.

- Wright EF, North SL. Management and treatment of temporomandibular disorders: A clinical perspective. J Man Manip Ther. 2009;17(4):247-254. doi:10.1179/106698109791352184

- Harrison AL, Thorp JN, Ritzline PD. A proposed diagnostic classification of patients with temporomandibular disorders: Implications for physical therapists. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014;44(3):182-197. doi:10.2519/jospt.2014.4847

- Wright EF, North SL. Management and treatment of temporomandibular disorders: A clinical perspective. J Man Manip Ther. 2009;17(4):247-254. doi:10.1179/106698109791352184