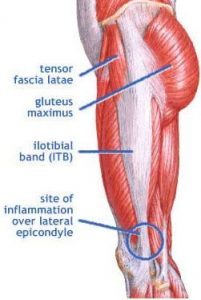

What is it? Iliotibial Band Syndrome (ITBS) describes an inflammation or irritation of the tract of connective tissue that runs along the outside of your thigh (your IT Band) at the point where it compresses against the thigh bone (femur) about an inch or two above the knee joint.

Pain is typically experienced along the outside of the knee and lower thigh. Pain is typically blamed on a rubbing or ‘friction’ as the band rubs over the bone with each stride. Recent research, however, challenges this long-standing belief and seems to indicate a repeated compression mechanism of injury. 1

Iliotibial band (ITB) syndrome is regarded as an overuse injury, common in runners and cyclists. It is believed to be associated with excessive friction between the tract and the lateral femoral epicondyle-friction which ‘inflames’ the tract or a bursa. This article highlights evidence which challenges these views. Basic anatomical principles of the ITB have been overlooked:

(a) it is not a discrete structure, but a thickened part of the fascia lata which envelops the thigh,

(b) it is connected to the linea aspera by an intermuscular septum and to the supracondylar region of the femur (including the epicondyle) by coarse, fibrous bands (which are not pathological adhesions) that are clearly visible by dissection or MRI

(c) a bursa is rarely present-but may be mistaken for the lateral recess of the knee.

We would thus suggest that the ITB cannot create frictional forces by moving forwards and backwards over the epicondyle during flexion and extension of the knee. The perception of movement of the ITB across the epicondyle is an illusion because of changing tension in its anterior and posterior fibres. Nevertheless, slight medial-lateral movement is possible and we propose that ITB syndrome is caused by increased compression of a highly vascularised and innervated layer of fat and loose connective tissue that separates the ITB from the epicondyle. Our view is that ITB syndrome is related to impaired function of the hip musculature and that its resolution can only be properly achieved when the biomechanics of hip muscle function are properly addressed. 2

Iliotibial band (ITB) syndrome is a common overuse injury in runners and cyclists. It is regarded as a friction syndrome where the ITB rubs against (and ‘rolls over’) the lateral femoral epicondyle. Here, we re-evaluate the clinical anatomy of the region to challenge the view that the ITB moves antero-posteriorly over the epicondyle. Gross anatomical and microscopical studies were conducted on the distal portion of the ITB in 15 cadavers. This was complemented by magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of six asymptomatic volunteers and studies of two athletes with acute ITB syndrome. In all cadavers, the ITB was anchored to the distal femur by fibrous strands, associated with a layer of richly innervated and vascularized fat. In no cadaver, volunteer or patient was a bursa seen. The MR scans showed that the ITB was compressed against the epicondyle at 30 degrees of knee flexion as a consequence of tibial internal rotation, but moved laterally in extension. MR signal changes in the patients with ITB syndrome were present in the region occupied by fat, deep to the ITB. The ITB is prevented from rolling over the epicondyle by its femoral anchorage and because it is a part of the fascia lata. We suggest that it creates the illusion of movement, because of changing tension in its anterior and posterior fibres during knee flexion. Thus, on anatomical grounds, ITB overuse injuries may be more likely to be associated with fat compression beneath the tract, rather than with repetitive friction as the knee flexes and extends. [/note]What we can say with some certainty is that the IT band and the pad of adipose tissue beneath it become inflamed or irritated while walking or running.

Who Get’s it? Estimates of prevalence are in the range of 5% – 14% of ‘active people’ and upwards of 30-50+% in distance runners. Women are affected more often than men.

What does it feel like? Symptoms of ‘Iliotibial Band Syndrome’ (ITBS) range from ‘sharp’ or ‘stinging’ pain (typically during exercise/activity) to a ‘deep aching’ (typically after activity).While running is the most common repetitive stress leading to ITBS, once ‘flared up’ you may feel these symptoms with basic daily movements such as getting up from a chair or turning a corner.

How to Diagnose? X-rays will not show this. An MRI or Ultrsound can demonstrate tissue changes that implicate ITBS, but this is expensive and unnecessary most of the time; conservative management has a > 90% success rate. 3 Iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS) is a common injury in runners and other long distance athletes with the best management options not clearly established. This review outlines both the conservative and surgical options for the treatment of iliotibial band syndrome in the athletic population. Ten studies met the inclusion criteria by focusing on the athletic population in their discussion of the treatment for iliotibial band syndrome, both conservative and surgical. Conservative management consisting of a combination of rest (2-6 weeks), stretching, pain management, and modification of running habits produced a 44% complete cure rate, with return to sport at 8 weeks and a 91.7% cure rate with return to sport at 6 months after injury. Surgical therapy, often only used for refractory cases, consisted of excision or release of the pathologic distal portion of the iliotibial band or bursectomy. Those studies focusing on the excision or release of the pathologic distal portion of the iliotibial band showed a 100% return to sport rate at both 7 weeks and 3 months after injury. Despite many options for both surgical and conservative treatment, there has yet to be consensus on one standard of care. Certain treatments, both conservative and surgical, in our review are shown to be more effective than others; however, further research is needed to delineate the true pathophysiology of iliotibial band syndrome in athletes, as well as the optimal treatment regimen. To Test if you have ITBS – assume a ‘narrow’ stance. Squat down slowly. If you reproduce your lateral thigh/knee pain at about a 30 > 45 degree knee bend, you may have ITBS.A clinical exam by your Physical Therapist can reliably determine the existence of ITBS.

What to do? Of course, as is the case with most repetitive stress injuries, there are a myriad of potentially contributing factors – poor sleep, poor nutrition, poor shoe selection (for sure!). Common ‘training errors’ that can increase the likelihood of ITBS include rapid increase in running (or hiking) volume, sudden increase in hill work (especially downhill), lack of ‘periodization’ or inadequate rest days, etc.Interestingly, studies show decreased biomechanical stress to the distal IT Band at faster paces. It seems speed work may, counter-intuitively, be less strenuous to the ITB than long slow jogs.Another common cause of ITBS is the introduction of running (or hiking/walking) on un-level surfaces. A quick / sudden transition to trails for instance. Other considerations are roads that are aggressively ‘banked’ to shed rainwater. Consider alternating which side of the road you run on and/or alternating the direction you run on a track. Better still, find a scenic deserted road and run in the center!(* Side note- this can also result from a poor bike fit. 4

This study examined force and repetition during simulated distance cycling with regard to how they may possibly influence the on-set of the overuse injury at the knee called iliotibial band friction syndrome (ITBFS). A 3D motion analysis system was used to track lower limb kinematics during cycling. Forces between the pedal and foot were collected using a pressure-instrumented insole that slipped into the shoe. Ten recreational athletes (30.6+/-5.5 years) with no known history of ITBFS participated in the study. Foot-pedal force, knee flexion angle and crank angle were examined as they relate to the causes of ITBFS. Specifically, foot-pedal force, repetition and impingement time were calculated and compared with the same during running. A minimum knee flexion angle of approximately 33 degrees occurred at a crank angle of 170 degrees. The foot-pedal force at this point was 231 N. This minimum knee flexion angle falls near the edge of the impingement zone of the iliotibial band (ITB) and the femoral epicondyle, and is the point at which ITBFS is aggravated causing pain at the knee. The foot-pedal forces during cycling are only 18% of those occurring during running while the ITB is in the impingement zone. Thus, repetition of the knee in the impingement zone during cycling appears to play a more prominent role than force in the on-set of ITBFS. The results also suggest that ITBFS may be further aggravated by improper seat position (seat too high), anatomical differences, and training errors while cycling. Prevention is KEY! Once ITBS is really flared up, it requires treatment and rest… yes, the ‘R’ word. A particularly bad case will take months to recover from. A little bit of ‘Proactive Rest’ (when symptoms are just starting) can go a long way. In mild cases you may be able to aqua jog or get on an elliptical while recovering. If you manage the initial onset of symptoms well, you could be looking at 4-5 days off with a graded return. Decrease training volume by 30-40% the first week and then ‘ramp up’ slowly and deliberately from there. An ‘acceptable’ pace for increasing volume for runners is variable and depends on many factors. However, for most runners the 10% rule will suffice – 10% increase per week max.In addition to addressing training errors – you will want to identify potential biomechanical stresses that lead to increased strain on the IT Band.

Consider the following:

Tightness in specific tissues surrounding the IT Band can contribute to ITBS. The IT Band itself does not, in fact, stretch. Studies show that the IT band is only capable of 0.5% elongation (That’s right, half of one percent – don’t bother). So we’re really talking about trying to stretch or ‘soften’ the muscles that surround and ‘tension’ the IT Band. Common muscles to address include the Tensor Fascia Late (TFL) muscle and the Vastus Lateralis (the outside portion of your thigh muscle).

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Leave a Reply

Click here to add your own text

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!