Hamstring “Strains”

What Is It?

The words ‘strain’ or ‘pull’ are somewhat arbitrary; both of these terms are referring to a tear of the muscle. These tears can be complete or “near complete” (subtotal) – but this is rare. More frequently we see partial tears. These are classified as either minor, or moderate depending on the extent of tearing. Most readers may be familiar with a grading system that the sports medicine community is trying to move away from. This system ‘Grades’ the tear according to the % of the muscle disrupted. Remember a muscle is really thousands of muscle fibers. These definitions defer slightly from source to source, but typically are close to the following:

Grade I – ‘Minor’ < 5% of total # of muscle fibers torn

Grade II – ‘Moderate’ > 5%, but < 50% of total # of muscle fibers torn

Grade III – Complete or Near Complete (Subtotal tears). This includes an injury where the majority of the fibers are torn but the fascia surrounding the muscle remains intact to some degree. Or a complete rupture (which is very rare).

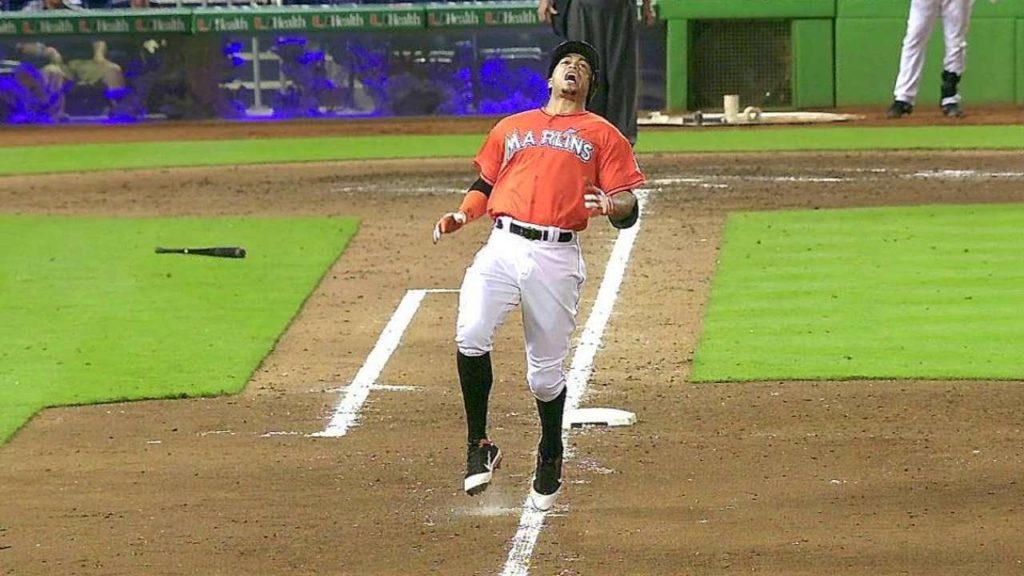

The tear happens suddenly and is often unmistakable – athletes frequently report feeling as though they’ve been stabbed!

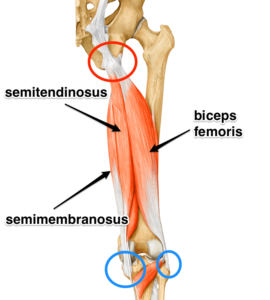

The majority of HS strains occur in the Biceps Femoris at the junction between the muscle and the tendon. Second most common, is a Semimembranosis tear, usually ‘high’ up in the tendon. 1

If the athlete hears an audible ‘pop’ when the injury occurs, it is more likely to involve the ‘free tendon’ it’s self – and more likely to require more time to recovery. 2

Mechanism of Injury

There appear to be 2 primary mechanisms for tearing your HS:

1) Stretch-Type Injury. This is common in dancers, hurdlers and place kickers. This injury often results in a ‘high’, Free Tendon tear involving the Semimembranosis tendon primarily. They tend to recover slower and require extended periods of time away from sport. 3 4

2) Sprinting Injury. With fast running, this injury occurs during the ‘terminal swing phase’, while the leg is fully extended out in front, just before making contact with the ground. 5

Who Gets It?

Hamstring strains are relatively common in sports – especially those requiring explosive acceleration and jumping. Sports such as Football, Soccer, and Track & Field are particularly perilous. Additionally, activities such as dancing, which require “hyper-stretching” movements, also place the participants at risk.

Quick Stats –

|

How to Prevent It?

Crucial to prevention is an understanding of the risk factors for a particular injury:

- Age – Yes, that’s right, your body’s not as resilient as it was “back in the day” and age has been identified by many studies to be a risk factor for HS injury. 10

- Weakness – Weakness of the hamstring muscles makes them more prone to injury. 11This vulnerability is exaggerated if you have really strong quadriceps; the imbalance (Dominant Quads with relatively weak HS) is a problem 12 13

- Weak “Core” muscles – We could do an entire book on what the term core strength means… but, for our purposes here, understand that the muscles around your trunk and hips help to stabilize your ‘pelvic girdle’ (where your HS muscles attach). Weakness and/or poor coordination / control of these muscles increases your risk of hamstring strains. 14 Recent evidence demonstrated that weakness of the Gluteus Maximus and Abdominal Muscles (in particular) increase your risk of sustaining a HS injury significantly. A 10% increase in Glut Max activation during swing phase reduces the risk by 20%!15

- Flexibility –Flexibility of the Hamstring muscle it’s self is not very important. Overly tight quadriceps and hip flexors however, place you at an elevated risk of a hamstring strain (more so than tight hamstring muscles). 16

- Deconditioning – There’s a reason why ~ 50% of hamstring strains occur in the pre-season. 17 Get your body into shape before starting any aggressive sports activity!

Don’t ramp up exercise activity suddenly; allow your body to adapt to the demands of the season.

- Past Injury – HS or Other. Past injuries is a risk factor for future injuries. This link appears to be far reaching. For example, a recent concussion puts you at an increase risk of musculoskeletal injury with sports participation (Cite). A past ankle sprain puts the athlete at an increased risk for both hip and knee injuries 18 19 20 A History of Low Back Pain, even without current Symptoms, appears to elevate the risk of knee injury with sports participation. 21

What’s the common thread here? Likely that these athletes demonstrate poor movement habits / strategies that put them at risk for a multitude of injuries.

A Prior HS injury, in particular, is the most significant risk factor (by far), more than doubling your risk for future HS tears. 22 23

Recurrence rates for athletes having suffered a HS strain are frustratingly high. A study of NFL athletes demonstrated a 22% recurrence. 24 Keep in mind, these are elite athletes, in their prime, rehabbing 4-5 hours a day, getting massages, acupuncture, adhering to a strict nutrition plan, sleeping in hyperbaric chambers, getting serial MRI’s every couple of days to monitor the injury – and about a quarter of them re-injury themselves!

Overall, re-injury rates hover around 1/3 for most sports, with the greatest risk of re-injury during the initial 2 weeks upon return to sport. 25

Not only that… but when HS tear do recur, the second injury is typically more severe than the first, requiring, on average, about double the time away from sport 26 27

Clearly sports medicine professionals want to do a better job here!

For our high-demand athletes and/or high-risk recreational athletes we strongly recommend the following – find a comprehensive pre-season training plan that incorporates sport-specific conditioning activities as well as an appropriate ‘balance’ of strengthening and mobility drills. Also, for those competing at high intensities, heavy eccentric training to the hamstring muscle is a must.

* Seek the advice of a Sports Physical Therapist or Strength & Conditioning coach *

What’s my Prognosis?

First of all – let’s be clear, HS muscle tears are highly variable. Factors such as severity/extent of damage, location of injury/tear and existence of a previous tear with scar tissue can all effect this answer. The range is 1 week > 16 weeks (or even beyond). If you want to put a finer point on this range… answer these questions:

1) Did the injury happen with running (shorter recovery) or from being over-stretched (longer recovery)?

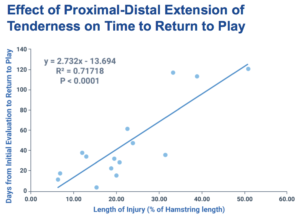

2) Do you feel the pain all the way up at the top of the HS muscle / at the attachment point near your ‘butt bone’, or ischial tuberosity (longer recovery)? Or part way down into the meat of the muscle (faster recovery)? 30 31 32

3) If you rub the muscle with your fingers, how much of the muscle hurts? If only an inch or two of the length of the muscle is painful, this indicates a quicker recovery than a 6 inch length of muscle being painful (not just sore). 33

The amount of pain you experience is not necessarily a great predictor of injury severity. This is due, in part, to the complex nature of pain perception. It may also be due to the fact that the intramuscular injuries perhaps hurt more, but are capable of healing quicker than the tendon injuries (muscle have more free nerve endings, but also a better blood supply for quicker healing) 34

One great predictor of recovery time, is how quickly your first week of recovery goes 35 so, get to a Sports Physical Therapist who is familiar with these types of injuries and do every thing right. Then, after 7-10 days, you will have a much better indication of how long your ultimate recovery is likely to be.

Advanced imaging, such as an MRI, may be taken by your Sports Medicine Physician if a Subtotal Tear or Complete rupture is suspected, or if there is any concern for an ‘avulsion fracture’ (when the HS tendon pulls so hard on it’s attachment point, that is breaks of a piece of bone). However, MRI’s do not appear to be helpful in predicting time to return to sport after acute hamstring injuries 36 37

“MRI variables alone explained 8.6% of the variance”… “which is unhelpful to players and coaches” 38

Now that I’m Injured… What Should I Do?

Acute Stage

This includes the first few days of a minor injury, or the first few weeks of a particularly severe injury.

Your Physical Therapist will attempt to reduce pain and gross swelling (yes inflammation is part of the healing process, but gross pooling of blood and fluid is not helpful).

You may be put on crutches if necessary to avoid a significant limp. Just Do It (to steal a line from Nike)… No one likes to use crutches, but it is important not to limp or ‘hold’ your knee partially flexed all day long. This puts added strain to the HS muscle as well as other areas of the body.

Also, you will likely be utilizing modalities to reduce pain and inflammation – Electrical stimulation may help to reduce reflexive spasm and or edema (swelling).

Ultrasound has not been shown to help the healing process for injured HS muscles and is potentially a waste of time. 39

You should ice the thigh for 15 minutes every hour for the first 48 hours at least (discuss with your PT).

* Importantly – Do NOT try to ‘stretch’ away the pain. You will only make the tear worse and recover more slowly. 40

If your Physical Therapist gives you a bunch of HS stretches to do

immediately after an injury – find yourself another PT.

These injuries should not be stretch for at least 10-14 days depending on the severity of injury 41

Also, do not rest it completely. Yes, with a bad muscle tear, a day or two of ‘total’ rest may be a good idea. But, that’s it! These injuries heal more completely when low intensity exercises are introduced very early in the recovery – This is where the recommendation must be customized to your individual circumstances; but you want to get stared early in order to:

- Prevent excessive scar tissue build up 42 (yes, a ‘scar’ is the first step in the healing process… your body lay a scar over the injured ‘stumps’ of torn muscle fibers. Then this scar gradually changes – or differentiates – into a fibrous union and then, eventually, into proper muscle tissue. But, excessive scarring down adjacent to the injury has been shown to occur with undue ‘complete rest’)

- Promote early healing by stimulating the cells that lay down new muscle fibers 43

Promote the strength of the ‘repair’ through proper ‘alignment’ of the new muscle fibers 44 and improved circulation of the regenerating tissue 45

So you should be moving and lightly exercising these injuries early. This should be pain free (or at least not causing additional pain) – the exact “right” dosage of exercise will be prescribed by your PT… and remember early is good!

* So, consult with a Sports Physical Therapist immediately after a HS muscle injury *

Sub-Acute Phase

This is the bulk of your recovery. You will be focused on:

1) General Conditioning – remember, we don’t want to send you back to the field deconditioned as that is a risk factor of a new injury!

2) Strength and ‘Control’ of adjacent body regions – We want strong and coordinated Hip/Pelvic and Trunk/Core muscles in particular 46 Your Physical Therapist will conduct a general movement screening to look for the quality of movement in your entire body as well as any weaknesses or mobility limitations that place undue stress on other parts of the ‘kinetic chain’ (Especially the Hamstring).

3) Gradual ‘Building up’ of strength and resiliency for the HS muscle specifically. Not only will this include heavier loads during exercise… but it should challenge the muscle through a wider range of motion (in particular – introducing strains with the muscle in a “lengthened” position.) 47 Also, we may introduce quicker movements and/or unexpected loads during more ‘functional’ or sport-specific tasks. Last, you will be asked to introduce ‘eccentric’ exercises to the HS. This includes loading the muscle up while it is lengthening 48 49

Your Physical Therapist will be focused on returning full mobility to the HS as well as all of the adjacent joints that may have stiffened up while in the ‘max protective phase’. Soft Tissue Massage and ‘Neuro-Mobilization’ may be useful to restore mobility 50) and prevent the Sciatic Nerve from being ‘scarred down’ during the healing process. 51

Instrumented Soft Tissue Massage can be used to promote a ‘stronger’ repair by promoting the metabolic activity of cells that laydown new tissue 52 and by promoting a proper alignment of these new fibers, which, ultimately, leads to an improved ‘load to failure’ 53 – a Good Thing!

Last, you will likely begin doing some light agility and sports-specific movement / drills.

Return to Sport Phase

This phase is highly dependent on your particular sports demands.

However, I can tell you, during this phase you absolutely should be doing heavy, hard, and explosive movements. You should be stressing the HS muscle in a variety of different movements, under a variety of different conditions, and during varying amounts of stretch 54 You should feel like you are working very hard!

The Hamstring muscle are exposed to enormous strain during full speed sporting activities. Your end-stage rehab should reflect this – otherwise you will not be ready to get back on the field and your chances of re-injury are substantial.

A compelling study published just last year by a leading researcher on the topic, demonstrated this point very well. They looked at many factors pertinent to recovery and successful return to sport. The most dramatic finding was the link between completing rehabilitation and recurrence risk. This study put all of the injured athletes through an extensive rehab program and found that those who completed their rehab, including a structured high-intensity & sports specific approach, until the return-to-sport criteria was met had a 0% re-injury rate (0 out of 43 re-injured). The athletes who rehabbed ‘most of the way’, but self-discharged and chose to return before the return-to-sport criteria was met had a 50% re-injury rate (4 of 8 athletes experienced a re-injury). 55

| Completed Rehab = 0% Re-injury

Incomplete Rehab = 50% Re-injury |

Makes sure you are working with a Sports Physical Therapist

with experience working with high-demand athletes AND

make sure to stick to your progression until completion!

At VASTA Performance Training and Physical Therapy, our clinicians are Sports and Performance focused. By leveraging the best practices of Rehabilitative Medicine and Strength & Conditioning, we’ll get you back in the game, preforming better than before your injury!

Experience the VASTA Difference – Request an appt. or call us today to get started immediately. 802-399-2244.

- Askling CM, Tengvar M, Saartok T, Thorstensson A. Acute first-time hamstring strains during high-speed running a longitudinal study including clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Am J of Sports Med. 2007;35(2):197-206.

- Heiderscheit BC, Sherry MA, Silder A, Chumanov ES, Thelen DG. Hamstring strain injuries: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, and injury prevention. J of Orthop & Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(2):67-81.

- Heiderscheit BC, Sherry MA, Silder A, Chumanov ES, Thelen DG. Hamstring strain injuries: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, and injury prevention. J of Orthop & Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(2):67-81.

- Askling CM, Tengvar M, Saartok T, Thorstensson A. Acute first-time hamstring strains during high-speed running a longitudinal study including clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Am J of Sports Med, 2007;35(2):197-206.

- Heiderscheit BC, Sherry MA, Silder A, Chumanov ES, Thelen DG. Hamstring strain injuries: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, and injury prevention. J of Orthop & Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(2):67-81.

- Elliott MC, Zarins B, Powell JW, Kenyon CD. Hamstring muscle strains in professional football players: a 10-year review. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(4):843-850.

- Bixler B, Jones RL. High-school football injuries: effects of a post-halftime warm-up and stretching routine. Family Prac Res J. 1992;12(2):131-139.

- Cross KM, Worrell TW. Effects of a static stretching program on the incidence of lower extremity musculotendinous strains. J of Athl Training. 1999;34(1):11.

- Orchard J, Seward H. Epidemiology of injuries in the Australian Football League, seasons 1997–2000. British J of Sports Med. 2002;36(1):39-44.

- Heiderscheit BC, Sherry MA, Silder A, Chumanov ES, Thelen DG. Hamstring strain injuries: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, and injury prevention. J of Orthop & Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(2):67-81.

- Zvijac JE, Toriscelli TA, Merrick S, Kiebzak GM. Isokinetic concentric quadriceps and hamstring strength variables from the NFL Scouting Combine are not predictive of hamstring injury in first-year professional football players. The American journal of sports medicine. 2013;41(7):1511-1518.

- Heiderscheit BC, Sherry MA, Silder A, Chumanov ES, Thelen DG. Hamstring strain injuries: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, and injury prevention. J of Orthop & Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(2):67-81.

- Zvijac JE, Toriscelli TA, Merrick S, Kiebzak GM. Isokinetic concentric quadriceps and hamstring strength variables from the NFL Scouting Combine are not predictive of hamstring injury in first-year professional football players. The American journal of sports medicine. 2013;41(7):1511-1518.

- Heiderscheit BC, Sherry MA, Silder A, Chumanov ES, Thelen DG. Hamstring strain injuries: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, and injury prevention. J of Orthop & Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(2):67-81.

- Schuermans, J., Danneels, L., Van Tiggelen, D., Palmans, T., & Witvrouw, E. (2017). Proximal Neuromuscular Control Protects Against Hamstring Injuries in Male Soccer Players: A Prospective Study With Electromyography Time-Series Analysis During Maximal Sprinting. The American journal of sports medicine, 0363546516687750.

- Gabbe BJ, Bennell KL, Finch CF, Wajswelner H, Orchard JW. Predictors of hamstring injury at the elite level of Australian football. Scandinavian J of Med & Sci in Sports. 2006;16(1), 7-13.

- Elliott MC, Zarins B, Powell JW, Kenyon CD. Hamstring muscle strains in professional football players: a 10-year review. The Am J of Sports Med, 2011;39(4):843-850.

- Gribble PA, Hertel J, Denegar CR, Buckley WE. The effects of fatigue and chronic ankle instability on dynamic postural control. J of Athl Training. 2004;39(4):321.

- Hubbard TJ, Kramer LC, Denegar CR, Hertel J. Contributing factors to chronic ankle instability. Foot & Ankle International. 2007;28(3):343-354.

- Bullock-Saxton JE., Janda V, Bullock MI. The influence of ankle sprain injury on muscle activation during hip extension. International J of Sports Med. 1994;15(06):330-334.

- Zazulak BT, Hewett TE, Reeves NP, Goldberg B, Cholewicki J. Deficits in neuromuscular control of the trunk predict knee injury risk a prospective biomechanical-epidemiologic study. Am J of Sports Med. 2007;35(7):1123-1130.

- Engebretsen AH, Myklebust G, Holme I, Engebretsen L, Bahr R. Intrinsic risk factors for hamstring injuries among male soccer players a prospective cohort study. Am J of Sports Med. 2010;38(6):1147-1153.

- Orchard J, Seward H. Epidemiology of injuries in the Australian Football League, seasons 1997–2000. Brit J of Sports Med. 2002;36(1):39-44.

- Elliott MC, Zarins B, Powell JW, Kenyon CD. Hamstring muscle strains in professional football players: a 10-year review. The Am J of Sports Med, 2011;39(4):843-850.

- Orchard J, Seward H. Epidemiology of injuries in the Australian Football League, seasons 1997–2000. Brit J of Sports Med. 2002;36(1):39-44.

- Brooks JH, Fuller CW, Kemp SP, Reddin DB. Incidence, risk, and prevention of hamstring muscle injuries in professional rugby union. Am J of Sports Med. 2006;34(8):1297-1306.

- Koulouris G, Connell DA, Brukner P, Schneider-Kolsky M. Magnetic resonance imaging parameters for assessing risk of recurrent hamstring injuries in elite athletes. Am J of Sports Med, 2007;35(9):1500-1506.

- Heiderscheit BC, Sherry MA, Silder A, Chumanov ES, Thelen DG. Hamstring strain injuries: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, and injury prevention. J of Orthop & Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(2):67-81.

- Askling C, et al. Total proximal hamstring ruptures: clinical and MRI aspects including guidelines for postoperative rehabilitation. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthoroscopy. 2013;21(3)515-33.

- Heiderscheit BC, Sherry MA, Silder A, Chumanov ES, Thelen DG. Hamstring strain injuries: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, and injury prevention. J of Orthop & Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(2):67-81.

- Askling C, Tengvar M, Saartok T, Thorstensson A. Acute First-Time Hamstring Strains During High-Speed Running. Am J Of Sports Med. 2007;35(2)197-206.

- Garrett WE, Califf JC, Bassett FH. Histochemical correlates of hamstring injuries. Am J of Sports Med. 1984;12(2)98-103.

- Askling C, Tengvar M, Saartok T, Thorstensson A. Acute First-Time Hamstring Strains During High-Speed Running. Am J Of Sports Med. 2007;35(2)197-206.

- Heiderscheit BC, Sherry MA, Silder A, Chumanov ES, Thelen DG. Hamstring strain injuries: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, and injury prevention. J of Orthop & Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(2):67-81.

- Jacobsen P, Witvrouw E, Muxart P, Tol JL, Whiteley R. A combination of initial and follow-up physiotherapist examination predicts physician-determined time to return to play after hamstring injury, with no added value of MRI. Brit J of Sports Med. 2016;50(7):431-9.

- Jacobsen P, Witvrouw E, Muxart P, Tol JL, Whiteley R. A combination of initial and follow-up physiotherapist examination predicts physician-determined time to return to play after hamstring injury, with no added value of MRI. Brit J of Sports Med. 2016;50(7):431-9.

- Wangensteen A, et al. MRI does not add value over and above patient history and clinical examination in predicting time to return to sport after acute hamstring injuries: a prospective cohort of 180 male athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:1579-87.

- Jacobsen P, Witvrouw E, Muxart P, Tol JL, Whiteley R. A combination of initial and follow-up physiotherapist examination predicts physician-determined time to return to play after hamstring injury, with no added value of MRI. Brit J of Sports Med. 2016;50(7):431-9.

- Heiderscheit BC, Sherry MA, Silder A, Chumanov ES, Thelen DG. Hamstring strain injuries: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, and injury prevention. J of Orthop & Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(2):67-81.

- Jarvinen T, et al. Muscle Injuries. The Am J of Sports Med. 2005; 33(5)745-64.

- Kaariainen M, et al. Correlation between biomechanical and structural changes during the regeneration of skeletal muscle after laceration injury. J of Ortho Research. 1998; 16(2)197-2016.

- Heiderscheit BC, Sherry MA, Silder A, Chumanov ES, Thelen DG. Hamstring strain injuries: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, and injury prevention. J of Orthop & Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(2):67-81.

- Powell C, Smiley B, Mills J, Vandenburgh H. Mechanical stimulation improves tissue-engineered human skeletal muscle. Am J of Physio. 1982;283(5)C1557-C1565.

- Magnusson S, Hansen P, Kjaer M. Tendon properties in relation to muscular activity and physical training. 2003; 13(4)211-223.

- Heiderscheit BC, Sherry MA, Silder A, Chumanov ES, Thelen DG. Hamstring strain injuries: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, and injury prevention. J of Orthop & Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(2):67-81.

- Sherry M, Best T. A Comparison of 2 Rehabilitation Programs in the Treatment of Acute Hamstring Strains. J of Ortho & Sports Phys Ther. 2004; 34(3)116-25.

- Askling C, Tengvar M, Thorstensson A. Acute hamstring injuries in Swedish elite football: a prospective randomized controlled clinical trial comparing two rehabilitation protocols. British J of Sports Med. 2013;47,935-93

- Askling C, Tengvar M, Thorstensson A. Acute hamstring injuries in Swedish elite football: a prospective randomized controlled clinical trial comparing two rehabilitation protocols. British J of Sports Med. 2013;47:935-93

- Petersen J, et al. Preventive Effect of Eccentric Training on Acute Hamstring Injuries in Men’s Scocer. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(11) 2296 – 2303

- Hopper D, et al. Dynamic soft tissue mobilization increases hamstring flexibility in healthy male subjects. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:594-98.

- Turl S, George K. Adverse Neural Tension: A Factor in Repetitive Hamstring Strain? J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998, 27(1)12-21.

- Davidson C, et al. Rat tendon morphologic and functional changes resulting from soft tissue mobilization. Official J of Am College Sports Med. 1997;29(3)313-19.

- Loghmani M, Warden S. Instrument-Assisted Cross-Fiber Massage Accelerates Knee Ligament Healing. J of Ortho & Sports PT. 2009;39(7)506-14.

- Brockett C, Morgan D, Proske U. Predicting Hamstring Strain Injury in Elite Athletes. Official J of Am College Sports Med. 2004; 379-87.

- Tyler T, Schmitt B, Nicholas S, McHugh M. Rehabilitation after hamstring-strain injury emphasizing eccentric strengthening at long muscle lengths: results of long-term follow up. J of Sport Rehab. 2016;26(2)131-40.

oWoDon’t ramp up exercise activity suddenly; allow your body to adapt to the demands of the season.

useful advice on recovery

Wow, some really useful advice in this article. I’m a soccer coach and the bane of my life is hamstring injuries, which my players are always suffering from.

Your advice around the different stages of recovery is spot on as I find my players try to rush back from injury.

Out of interest is there a minimum amount of time that you’d recommend before returning to full activity?

thanks,

Martin

Thanks for the response Martin. Yes, for soccer players, HS injuries are HUGE!

As for a timeline… it’s variable. Greatly so. A small ‘tweak’ may be more of a cramping phenomena (see our blog on cramping) and be appropriate to return a day or two later… whereas a large tear will take many months.

The key is to complete rehab to a high level.

Many PT’s don’t do a good enough job getting their athletes back to a level where they can really handle the high intensity, explosive and unpredictable loads associated with soccer. When your athlete tells you they’ve been ‘cleared’ to play, ask them ‘what tests did they run you through?’. They should have a a whole battery of tests that they had to perform to demonstrate ‘Return to Sport Readiness’. Otherwise, their PT is just guessing. I would ‘phase’ them back with ‘predictable’ 3/4 speed drills first… then predictable full speed drills and unpredictable (reacting / defense) drills at 3/4 speed second. Full speed, unpredictable drill and play last once the athlete looks comfortable with everything else.

And – If possible – Prevention is preferable…

Get your kids doing a good off season conditioning program and a pre-season injury prevention program including (at the very least):

1) Pelvic/Core Strength & Conditioning

2) Heavy HS Eccentirc Loading (Nordic Curls are an easy example)

3) Hip Flexor Stretching

Hamstring injuries do NOT need to be as prevalent as they currently are.

Good luck!