Femoroacetabular Impingement

“Hip Impingement” and “Femoroacetabular Impingement” describe an abnormal contact, rubbing, or pinching or the bones around the hip joint. More specifically it is a “motion-related clinical disorder of the hip involving premature contact between the acetabulum and the proximal femur” which may result in (but does not always result in) a classic set of symptoms, signs and findings on imaging. Before we discuss FAI specifically, a little context…

The general term for pain arising from inside the hip joint its self is ‘Intra-articular’ hip pain. While commonly mistaken as groin / muscle strains, Intra-articular pain is a distinct injury. “Intra‐articular hip injuries are frequent sources of hip and groin pain in athletes that are not related to the musculotendinous structures around the hip and groin”. In the hip joint, there are a few common sources of intra-articular pain. First – in the aging population, we commonly see Osteoarthritis in the hip joint. We can see this relatively early (we’re talking ~ 40 and up here) especially if you’ve been active in high impact, high loading, and/or cutting& pivoting sports throughout your youth. What we will focus on in this blog is Intra-articular hip pain in the youth athlete ( ~ 30 and under) and the ‘pre-arthritic’ population ( ~ 30-45 +/-). The most common source of intra-articular hip pain in these groups include Chondral Lesions (Articular Cartilage defects), Acetabular Labral Tears (ALT), and Femoral Acetabular Impingement (FAI).

Chondral (Articular Cartilage) Lesions

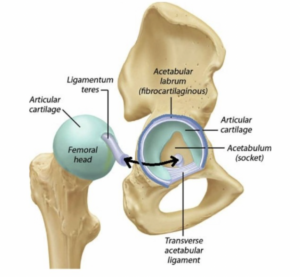

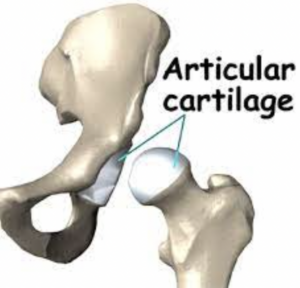

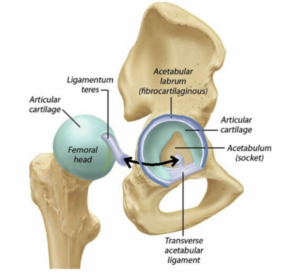

Like most of the joints in the human body, the hip joint is ‘lined’ with hyaline cartilage. We refer to this as Articular Cartilage. The weight bearing portion of the acetabulum (socket) and the entire head of the femur (ball) is covered in Articular Cartilage.

This layer of hyaline cartilage can be disrupted resulting in a loss of the protective coverage in a particular location. This can be a result of repetitive motion (common in dancers and martial artists), or as a result of one time trauma. When a distinct and focal disruption occurs, among otherwise healthy cartilage, this is referred to as an Articular Cartilage Lesion or Chondral Lesion. Different from the more generalized degradation that occurs in Osteoarthritis. In the case of a Chondral Lesion, the lesion can result in a catching, snapping or locking sensation. Also, the underlying bone is exposed to an abnormal amount of loading which can cause pain and potentially lead to accelerated arthritic changes.

Acetabular Labral Tears

The Acetabular Labrum (AL) is a band of fibrocartilage that circles around the outer edge of the acetabulum, deepening the socket.

The AL increases the articular surface area by 22%, dispersing compressive forces; The AL also increases acetabular volume by 33% and is believed to create a suction-cup like seal in the hip joint (contributing to joint stability and reducing shear forces)

The AL contains ample free nerve endings and sensory organs in its more superficial layer –likely contributing to proprioception (joint position sense) and (importantly) can be a source of pain.

Tears of the AL can also occur as the result of repetitive movement, or singular trauma (catching your ski on a gate). In addition to pain, these tears contribute to feelings of instability, grinding, catching, locking and/or giving way sensations.

Intra-articular hip pain (pain arising from structures inside the joint) can be the result of various issues besides boney impingement (FAI)

– Chondral (Articular Cartilage) Tear

– Acetabular Labral (Fibrocartilage) Tear

– Joint Laxity/Hypermobility (Which leads to pain from multiple tissue sources)

– Intraarticular Ligament tear (ligamentum teres or transverse ligament)

– Osteoarthritis

It is important to note that these injuries often co-exist.

(Thus, it’s difficult to discuss one without discussing them all)

*** Additionally, there are many potential causes of hip pain that are outside of the joint (or ‘extraarticular’). This would include tendonitis, ‘snapping’ tendons, muscle or tendon tears, bursitis, and nerve entrapments. We will not look at muscular strains, tendonitis, or other forms of ‘Extraarticular” (Outside of the hip joint) pain here. Interested readers can find quality information here: Hamstring Strains, Groin/Adductor Strains, Lateral Hip Tendonitis / Bursistis. We will also not look at boney fractures (high-energy fracture or stress fracture) although this

may need to be considered depending on the particular injury presentation and history.

Femoro-Acetabular Impingement (FAI)

OK… Back to FAI. As we said, FAI occurs “when there is abnormal contact of the femur with the acetabulum”

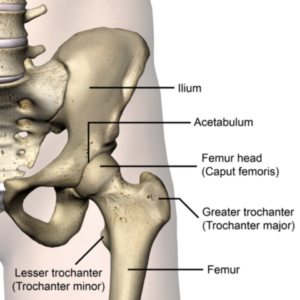

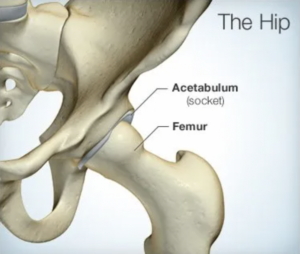

As you can see in these images, the hip is a ball-and-socket joint. The Femur is the long bone of the thigh, which contributes the ‘ball’ of the hip joint. The Acetabulum is the ‘socket’ of the pelvis. Femoro-Acetabular Impingement (FAI) occurs when these structures abut each-other in a way

that causes pain and can potentially limit range of motion. See video:

[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Q11jjHguPI&t=2s]

The exact structures that ‘impinge’, and the underlying cause(s), are multiple and will be discussed below.

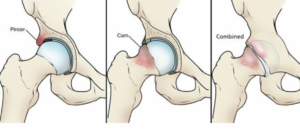

There are essentially 3 ‘Types’ of FAI.

“Cam” Impingement – where the femoral head is enlarged causing increased compression and shearing on the acetabular rim. (This anatomical finding may be referred to as “a Cam lesion” “Pincer” Impingement – where the acetabular abnormality (increased ‘over-hang’) results in impingement against a normal femoral neck (This anatomical finding may be referred to as “a Pincer Lesion”) “Combination” – A mixture of Cam and Pincher, which is the most common

What does FAI feel like?

If you do have symptomatic FAI it most commonly is experienced as a combination of

symptoms potentially including:

– Pain deep in the joint and/or the groin

– Occasional sharp pain in hip and/or groin – especially with movements of hip flexion

and/or rotation.

– Intermittent ‘Catching’ or ‘Locking’ sensation

– Grinding / Crepitus sensation in the hip socket

– Pain with prolonged sitting

– Radiating pain into the hip/buttock, groin and/or thigh

How Is FAI Diagnosed?

“Big Picture”… Typically this diagnosis is made with a combination of X-rays and Clinical Exam.Multiple measurements will be made from plain film X-rays to classify the existence of boney morphology that qualify for a diagnosis of FAI. (Lots of detail here if you’re interested)

A clinical exam will attempt to confirm that boney impingement is in fact causing (or at least

major contributing factor to) your pain – and not just an incidental ‘finding’. (FAI signs appear

on hip X-rays of 42.6% to 53% of asymptomatic individuals)

While an MRI is not required to make this Diagnosis.

it may be utilized to assist in making surgical decisions (e.g. to visualize the extent of cartilage damage or existence of OA in the joint prior to surgery as this may affect your post-op expectations, etc.) and/or to rule in/out other pathology.

“The Details”…

First, it’s important to understand 2 things:

1) Boney abutment of adjacent structures (2 bones contacting each other) is something that is not necessarily a problem. This happens normally in our shoulders, elbows, spine, ankles, toes, etc. This is not dysfunctional or painful. It is only considered pathological when the boney abutment is associated with significant boney deformity, a loss of motion, and/or pain. 2) FAI rarely occurs in isolation. Typically, there is weakness, and/or damage and/or structural anomaly to surrounding structures that contribute to faulty mechanics and altered loads through the joint. Boney changes take place (over time) as a result of this. In some cases, the boney changes could be considered a result of an underlying problem, not the initial problem itself. Even so, as the pathology progresses, the boney changes themselves can eventually become the problem. This explains why we see such a high rate of associated ‘comorbidities’ in patients with FAI – such as, labral tears and chondropathy (cartilagedamage). It also underpins the high correlation of future hip Osteoarthritis

So, given that some level of boney abutment is normal; and considering that boney morphology typically associated with FAI have been commonly found in asymptomatic people… we must ask

– How often might Xray and/or MRI findings suggestive of FAI, be incidental findings? One large review in the journal Arthroscopy showed that when imaging is performed on asymptomatic folks > 65% were found to have labral tear and boney morphology sufficient to meet the definition of FAI ( cite-

Some variability in anatomy is potentially unrelated to pain and/or mobility limitation.

But this is not always the case. Thus, FAI can be tricky to diagnose…

When do findings implicate pathological FAI?

When does this pathology requires treatment?

What intervention is most indicated (Surgery vs PT vs Injection)?

When is surgery required?

The answer is – it depends. It likely depends on a number of variables, not all of which have been completely teased out with 100% confidence at this point. But we know MUCH more than we knew 10-15 years ago; and the picture is beginning to get more clear.

An example

19 year-old male soccer player. He has been playing soccer since he was 4. He has had intermittent groin pain on the right (dominant) side for the past ~ 2 years, but nothing that required him to stop playing for any length of time. X-rays show a ‘cam’ lesion of the effected hip. What now? What we know – Playing sports as a young kid, especially if an athlete specializes at a young age, will likely lead to some adaptive changes to the athlete’s body – and that includes the boney skeleton. Sports that place a repetitive torsional stress through the hip (as soccer does) can lead to boney changes in these bones. One study of elite soccer players found bony hip ‘abnormalities’ in > 70% of male players. cite – Thus, a ‘cam’ lesion, and/or altered rotation (or ‘version’) of the long bone of the femur is so common it’s to be expected in this population. Cite –

So What –

Based on this finding alone, the athlete would not be considered a good surgical candidate. Almost certainly a course of Physical Therapy would be the first intervention. Perhaps along with an anti-inflammatory injection depending on pain severity (among other consideration).

The reality is that the decision around whether or not any one particular patient is a surgical candidate depends on many factors – beyond the scope of what we could cover here. But, to give you some sense, it includes the following considerations:

– Pain levels

– Time frame

– Age of the athlete

– Activity/Competitive level

– Sports participation

– Realistic post-op expectations

– Findings of degenerative changes (‘Moderate’ or worse)

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3557322/)

– Boney alignment out of ‘normal’ ranges (socket angulation, socket depth, femoral neck angulation, ration of ‘ball’ to ‘neck’ size/thickness, etc)

– Findings of hip dysplasia

– Hip hyperlaxity

– Findings of ‘loose bodies’

– Severity of damage (‘irreparable’?)

And more…

For these reasons, the decision-making process needs to be assisted by the expertise of an Orthopedic specialist with experience specifically in this area. PT will be the best first route for the vast majority of patients with FAI. MOST of the time (but not all of the time) even if you are considered a surgical ‘candidate’, an orthopedic surgeon will recommend you commit to at least 4 months of Physical Therapy before going under the knife. If you are improving, then surgery will not be recommended. And if it is determined that surgery is still the best route, you will go into it a bit stronger and (hopefully) much more aware of movement patterns & habits that contribute to the pain (and strategies to modify those activities).

PT will be the best first route for the vast majority of patients with FAI.

MOST of the time (but not all of the time) even if you are considered a surgical ‘candidate’, an orthopedic surgeon will recommend you commit to at least 4 months of Physical Therapy before going under the knife. If you are improving, then surgery will not be recommended. And if it is determined that surgery is still the best route, you will go into it a bit stronger and (hopefully) much more aware of movement patterns & habits that contribute to the pain (and strategies to modify those activities).

How can Physical Therapy Help?

Commonly folks will express the following concern: If my pain is caused by boney abnormalities ramming into each other, how can I fix this without surgery? The answer is 2-fold. 1 st – bones bump into bones all of the time! (As we’ve already discussed). It does not always hurt. If you straighten your elbow out as far as possible, you are eventually stopped by bones bumping into one another. This has also been shown to occur in the hip. The bones of the femur and acetabulum bump into one another without pain commonly. So, it’s not so simply as– “break out the bone saw”!

2nd – There may not always be a great surgical ‘solution’ to your pain. Depending on many factors the outcomes following surgery for FAI are not always a 100% ‘Fix’. In some cases, results from proper conservative management may be very similar to surgical intervention. In other cases, surgery may be preferrable and/or offer better long-term results. Since it is not always easy to be sure which category any particular patient falls into, a ‘trial’ of Physical Therapy is often (although not always) the best route.

So, Physical Therapy is very often the first option, to reduce pain, improve mobility and improve function.

What does PT for FAI look like?

Physical Therapy for FAI will be highly individualized as the ‘causes’ and/or contributing patho-mechanics are different for every-body. However, certain patterns and common findings do exist. Here are some common areas of focus:

Hip Mobility

Research has shown that patients with FAI (and/or Acetabular Labral Tear) often present with a loss of hip joint mobility. Most commonly we see a loss of hip flexion, internal rotation, and abduction. It is common to find loss of

hip extension as well.

Reduced hip mobility will adversely affect the athletes’ performance as athletic movement require full, clean hip mobility. Also, reduced hip mobility (especially reduced abduction, and extension) has been linked to an increased risk of other injury in the athletic population.

One aspect of the rehabilitation approach will be to normalize hip mobility.

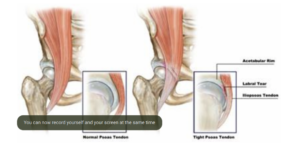

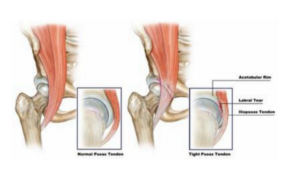

Example – Psoas Muscle Tightness. Impairments in hip flexor flexibility can alter the joint mechanics of the hip and restrict normal movement patterns. Research has suggested that psaos restrictions can exacerbate, and potentially even lead to, labral pathology.

Example – TFL Hyperactivity/Tightness. “If the Tensor fascia latae (TFL) dominates hip flexion movement instead of the iliopsoas, normal arthrokinematics are compromised since the TFL inserts at a relative greater distance from the joint axis creating an internal rotation bias with hip flexion”– (Sahrmann, S. (2002). Movement system impairment syndromes. St. Louis: Mosby.) Studies have confirmed that anterior muscle imbalances do in fact result in altered compressive forces in the anterior aspect of the hip (where labral tears most commonly occur)

Example – Posterior Hip Rotator Muscles. The deep rotator muscles in the back of the hip are somewhat similar to the rotator cuff of the shoulder. They provide rotatory movement and contribute to joint stability. Also, they may alter joint mobility when restricted. With “a decrease in posterior joint play. Lack of posterior femoral glide will create an impingement during hip flexion as the femoral neck hits the acetabulum.”

Hip Strength

Sufficient hip muscle strength is essential to stabilize the joint and dissipate ground reactive forces (think shock absorption). The ‘balance’ of muscle strength & sequencing of muscle firingpatterns is important as well – especially for higher level activities / athletes.

Another area of focus in the rehabilitation approach will be to build & balance hip strength

Example – Gluteal Weakness. Gluteal weakness has been shown to alter normal hip joint Weakness of the lateral hip muscles (Gluteus Medius primarily) in particular, is a commonfinding in patients with pathological FAI / ALT. Studies of patients with unilateral pathology (only effecting 1 hip) suggest that this is not simply a finding of general weakness in these patients, but a specific finding correlated with the pathology.mechanics and be associated with increased anterior hip joint forces

Example – Psoas Weakness. Hip flexor weakness has also been linked to FAI and ALT. Deep layers of the Iliopsoas muscle have attachment directly onto the anterior capsule of thehip, and proper function is thought to prevent pinching of the capsule during active hip flexion.

Example – ‘Core’ Weakness. Lets avoid the lengthy dialogue around what exactly is ‘core weakness’. Suffice it to say, weakness of the core muscles has been linked to altered pelvic and leg alignment (Claiborne TL, Armstrong CW, Gandhi V, Pincivero DM. Relationship between hip and knee strength and knee valgus during a single leg squat. J Appl Biomech. 2006;22:41–50 ) (Willson JD, Ireland ML, Davis I. Core strength and lower extremity alignment during single leg squats. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38:945–952 ). Also, a “correlation between weakness in the hip and core and lower extremity injuries has been established”

It is widely agreed that a component of core and pelvic muscle conditioning & coordinationshould be a component of any comprehensive approach to rehabilitation for FAI.

Movement Pattern Coordination

There is evidence to support the correlation between FAI/ALT and altered movement patterns/movement dis-coordination – including alterations in muscle firing amplitudes, sequencing, andmovement mechanics.

Example – Altered Running Mechanics. “Limiting hip adduction and internal rotation during Increased “femoral adduction” (knee knocking in or

hip dropping) has been linked to various injuries in the knee and hip joints during running.functional activities has been shown to decrease hip pain in a runner with FAI and labral tear”. Measurement of vertical ground reaction forces (VGRF) is one way to estimate forces on the hipduring walking and running. VGRF during walking is estimated to be 1.15 x bodyweight for females and 1.23x bodyweight for males. Jogging forces are estimated to be 2.36x bodyweight for

females and 2.45x bodyweight for males. You can see how the alignment of the pelvis and leg would be important under such strain. Also, the role of your

lower extremity muscles to help attenuate these forces is key!

There are nearly endless examples that could be given: muscle firing timing & balance between deep core muscles and local hip muscles when performing common exercises such as Gluteal bridges, Hip thrusters, Lunges, etc.

Balance of hip mobility and muscle recruitment efficiency during multi-joint movements like Deadlifts and Squats. We could go on indefinitely here.

A rehabilitation approach will also include a detailed movement assessment and a movement re-education / re-training progression when appropriate.

By giving you the above ‘common examples’ we hope to highlight that the rehabilitation for FAIis nuanced, and highly individual. Any resource offering to give you suggestions for “3 good exercises for FAI” or “Best stretched for fixing FAI” is providing a dis-service.

Find a PT you trust and commit to a custom plan that is based on your unique profile/presentation and progressed based on your goals.

Expect to commit to at least 4 months, however, this (also) is fairly individualized.

What does surgery look like?

The last ~ 15-20 years has seen a steep learning curve surrounding surgical treatment for FAI. As is the case with most ‘new’ surgical techniques, there was a period of time where FAI was “over-surgerized”. Patient selection was too broad. Emphasis on attempts at conservative management (ie 4-6 months of Rehab) before jumping to surgery were insufficient. Generally, the limitations of the surgery its-self were not fully understood or properly communicated to

patients. Frequency of surgical intervention for hip pain soared and outcomes were not always great. More recently, this has improved dramatically. Let’s consider where we are now: Broadly speaking, one is considered a surgical candidate if they:

1) Are non-responsive to proper ‘conservative’ management – rehabilitation with or without steroid injection.

2) Lack evidence of advance degenerative changes (Osteoarthritis) in the hip joint.

3) Meet certain ‘thresholds’ of boney morphological pathology are measured on imaging

* Details here – https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3303012/

(Warning, this article will get you deep into the weeds – you’re better off consulting

with an orthopedic surgeon who specializes in hip arthroscopy!)

4) Lack of any ‘general’ contraindications to surgery (e.g. active infection, anesthetic risk, etc)

5) Understand the post-op protocol, rehabilitation requirements and agree to commit to both.

* Each case is somewhat individualized and consultation with an orthopedic surgeon who specializes in the hip is of great value here. Individual considerations (e.g. obesity, hip instability, acetabular dysplasia, etc.) may be central to the discussion of ‘candidacy’ and ultimate outcome expectations –

2 important conversations to have.

Arthroscopic surgery for FAI commonly includes multiple components. While it is beyond the scope of this resource to summarize surgical techniques & approaches for FAI… the second half of the video below gives a very basic overview / animation of arthroscopic approaches for FAI and AL repair (start at the 2:00 mark)

As far as expectations after surgery – this also is heavily individualized. What you should expect is:

1) Some soreness and pain post-operatively. There’s no way around this. The surgery involved drilling and scrapping into your bones, poking holes through your soft- tissues, etc. You should not expect to skip home afterwards!

2) Some period of time limiting your weightbearing to a degree (using crutches). Some patients may be partial weightbearing almost immediately and aiming to walk normally without crutches after just a few weeks (~ 4 +/-). However, some

procedures (cartilage salvage, ‘microfracturing’, etc) may require you to be mostly

off loaded for up to 2 months.

3) A Prolonged Rehabilitation period. The structured rehabilitation period will be in the ballpark of 3-6 months. Again, highly individualized. Need for continued exercise to further build back strength and endurance may go beyond this – but typically some degree of later-stage recovery can be done independently at a gym (or even at home).

Rehabilitation will not also be easy. Nor will your recovery always be linear (eg. a little better every day with no ‘steps back’). Expect to have to work with your Physical Therapist or Athletic trainer to problem solve along the way.

All of this said –

Find a place and/or a Person that you trust to guide you through this process and commit!

If you are experiencing any of the above listed signs and symptoms and you would like to have your hip evaluated by a sports and orthopedic specialist – Call us at 802-399-2244.