Headaches

Headaches are the most prevalent pain disorder, effecting 66% of the general population.1

Cervicogenic headaches (CGH) are characterized by pain referred to the head, from the cervical spine. 2 3 For this reason, they may also be referred to as “Neck” headaches.

CGH are fairly common, 4 5 6 but the exact prevalence is not entirely known.7 Among the headache population, estimates exist from 13.8% – 35.4% 8 9 10 11 12 and among patients with headaches after injury / whiplash, the prevalence is as high as 53%. 13

Since the initial coining of the phrase “cervicogenic headache” in 1983 by Sjaastad et al 14 there has been some controversy about it’s existence, and some have questioned it’s existence as a separate and distinct clinical disorder. 15 16 This is likely due to the fact that some of the clinical features of CHA – such as neck pain or cervical muscle tenderness – can also be present with other HA ‘types’ (e.g. a Migraine). 17 18 19 20 21

None-the-less, there has been a growing consensus regarding the existence of CGH 22 23 24 25 and The International Headache Society recognizes CGH as a distinct disorder. 26

A substantial body of evidence exists to support the phenomenon of head pain as referred from the neck – both from bony structures, 27 joints,28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 and soft tissues (muscle, ligament, disc, etc). 36 37 38 39 40 41 In fact, there is increasing awareness that this phenomenon may be becoming more prevalent problem as a result of the increased use of laptops, tablets and phones.

Studies have reported a significant impact on the quality of life of patients that experience CGH – with an even greater detriment to physical functioning then is experienced by Migraine sufferers. 42

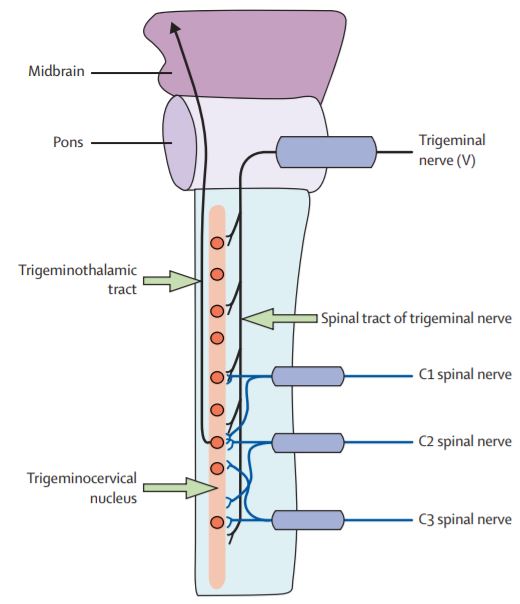

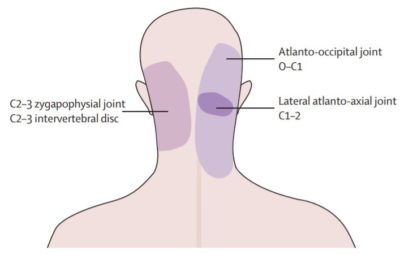

Common sources of dysfunction contributing to the referral of pain to the head, and subsequent CGH, include the joints of the upper three vertebrae of the cervical. These joints are innervated by the C1 spinal nerve, C2 spinal nerve, and C3 spinal nerve respectively.

The mechanism for this pain “referral” pattern is complex. In short, the Trigeminal nerve (which innervates multiple regions of the head and face) is in close proximity, and appears to interact with nerves traveling from the upper cervical spine.43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 This “functional intersection… is thought to allow the bidirectional transmission of a pain signals between the neck and the trigeminal sensory receptive fields of the face and head.” 56 57 58 59

Essentially, the wires get crossed. (A similar mechanism explains why patients experiencing a heart attack perceive arm pain.)

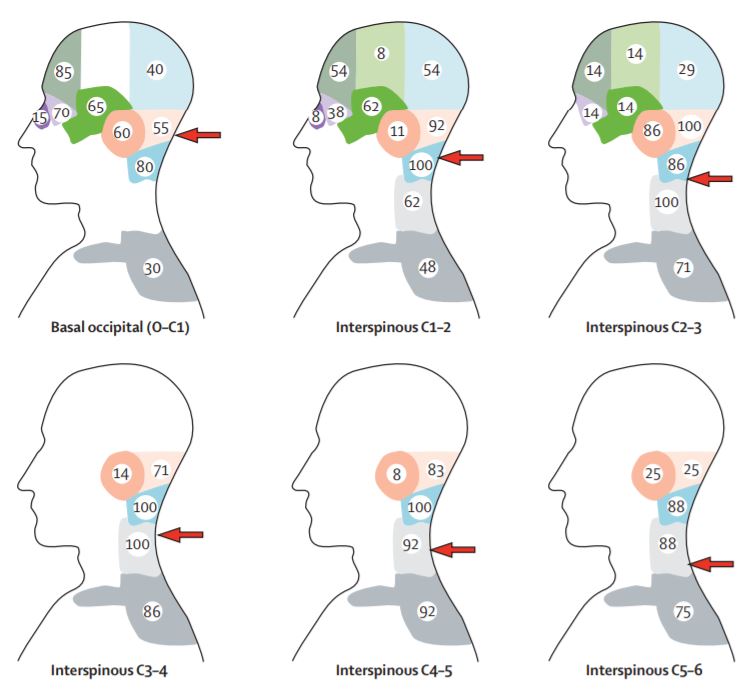

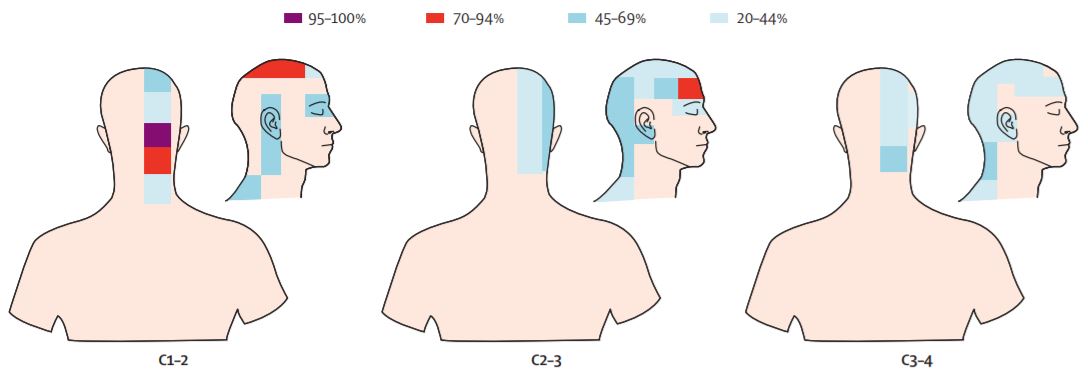

This “convergence” has been demonstrated in anatomical studies and in laboratory animals.60 61 62 63 64 Researchers have demonstrated this phenomena in humans with forced distension (swelling) of the C2/3 and C1/2 joints through guided injections, resulting in pain radiating to the uni-lateral upper neck and occipital regions of the head 65 66 – effectively reproducing the classic Cervicogenic Headache pain pattern.

Research implicates the C2/3 ‘facet joint’ as the most frequent source CHG, accounting for up to 70% of cases.67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 This segment appears to be particularly problematic for patients with a history of chronic neck pain and headache following a whiplash injury.78 The C1/2 segment is believed to be the second most common source of CHG, although the exact frequency is unknown. 79 80 81 82 83 Less common sources of CHA include the C3/4 facet joints, 84 the upper cervical muscles 85 86 87 (* Some sources claim that HA derived from myofascial structures should be classified as Tension-type headache, but this is not universally accepted)88 and the Intervertebral discs of the upper cervical spine (in cases of pathology or degenerative changes).89 90 91 92 93 94 95

The joints in the lower cervical spine have been implicated in some studies, 96 97 98 99 100 but a definitive link to causation has not been shown101 and there is no neuroanatomical link to provide an explanation for this. Some suggest that a plausible explanation is that the pain really is from the upper cervical spine; When researcher’s relief painful lesions of the lower cervical spine surgically (or with injections), this leads to a reduction in muscle tension, that, relieves pressure on the painful upper cervical joint and in turn reduces the referred head pain.102 103

Diagnosis

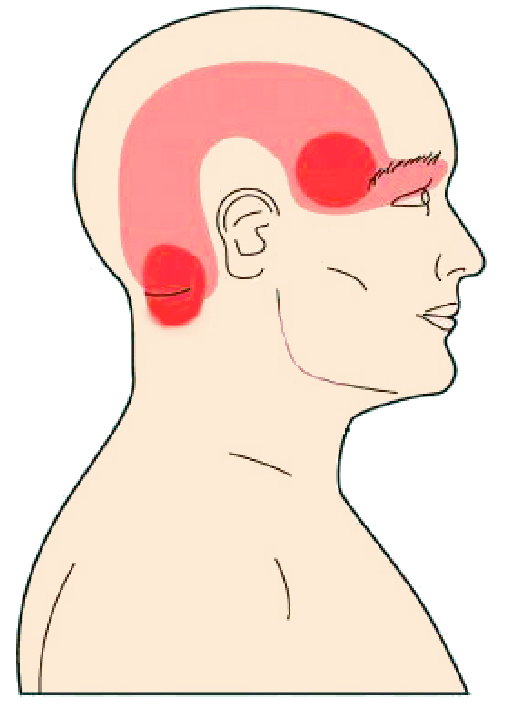

CHG is characterized by unilateral head pain that is triggered or increased with movement of the head, neck, or (more commonly) with sustained postures (typically poor posture). 104 105 106 Intensity can fluctuate greatly and is often “moderate” to “severe”. Pain commonly radiates from the occipital region to the temporal and frontal regions. 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 This is an important differentiating characteristic of CGH. While the areas of pain with CGH can overlap with those of other types of headache (e.g. Migrain, Tension HA, etc), the pain almost always starts in the occipital region with CGH, which is unique.114 115 116 117 118

While pain can be present bilaterally, it is asymmetrical (always worst on one side). Commonly, but not always, patients with CHG will also complain of neck pain and/or shoulder pain. Restricted neck range of motion is also typically present 119 although the patient may not be acutely aware of this. Commonly, neck extension and rotation is impaired120 121 122 (A positive “Flexion-Rotation Test” has been shown to differentiate CGH from asymptomatic patients and/or patients with Migraine with 91% sensitivity & 90% specificity 123 124).

Importantly, the pain from CGH is non-throbbing and rarely associated with visual disturbances, photophobia (severe sensitivity to light), or phonophobia (severe sensitivity to sound).

In cases where it is imperative to definitively implicate the upper cervical joints as the source of pain, a diagnostic anesthetic nerve block can be performed.125 126 However, this is often not readily available, 127 and it is postulated that a diagnosis of CHG can be made in certain cases without requiring such an invasive procedure. 128 This can be done with a careful history, a complete neurological assessment, and with the presence of a combination of signs and symptoms that implicates CHG as the most likely cause of pain.

One study revealed that a ‘cluster’ of a) restricted neck movement, b) (+) manual examination for upper cervical joint dysfunction and c) impairment of the deep neck flexors muscles (identified by the “Craniocervical Fexion Test) had 100% sensitivity and 94% specificity to identify CGH. 129

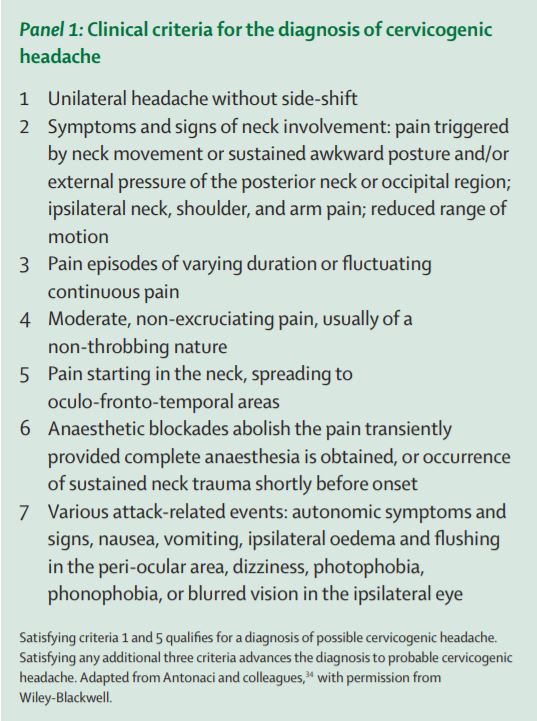

Another study, by Antonaci and colleagues 130 developed a “panel” of Signs and Symptoms that implicate CGH.

Imaging tests, such as X-ray, MRI and CT scans cannot diagnose CGH. 131 132 133 134 135

What Causes CGH

CGH typically occurs insidiously, perhaps the result of repeated movements or poor postural strategies. While there is often no specific precipitating event that ‘causes’ the onset of CGH’s, neck injuries are capable of triggering this phenomena.

“Post Traumatic Headache” is common in the population of patients after a whiplash injury. Estimates of frequency are as high as ~ 88%.136 While these headaches can be attributed to multiple phenomena (e.g. concussion, autonomic responses, etc.), many are thought to be from the cervical spine. Studies investigating this using diagnostic injections to block sensation from the upper cervical joints report that more than half (~54%) appear to be to be cervicogenic in nature.

The typical presentation for Cervicogenic Headache includes: 137 138 139 140

- Unilateral Head pain – emanating from the occipital region(s). (Bilateral pain is less common, but possible. Usually asymmetrical) 141 142 143

- Ipsilateral (same sided) neck, shoulder or arm pain may be present.

- Pain is recurrent, long-lasting and moderate to severe. 144

- Pain is triggered or worsened with cervical movement and/or awkward postures 145 146 147 148

- Pain with palpation of the upper cervical joints and or adjacent musculature 149 150 151 152

- Restricted cervical range of motion – especially Extension and Rotation 153 154

While The occiput & temporal regions of the head are most common/classic, periorbital radiation is not uncommon. Additionally, pain referral to the face, frontal and parietal regions are possible 155 156

Additionally, we should expect the absence of signs and symptoms that implicate other likely diagnosis (e.g. Migraine, Cluster HA, etc), although the “occasional presence” of symptoms such as photophobia or phonophobia, dizziness, and unilateral blurred vision are possible. 157

Differentiating from Migraine

As stated earlier some of the clinical features of CHA – such as neck pain or cervical muscle tenderness – may also be present with Migraine.158 159 160 161 One study reported the presence of neck pain or stiffness in 64% of Migraine sufferers. 162 In another study, neck pain was present during migraine attack 75% of the time.163 This pain was unilateral and ipsilateral (same side) to the headache 98% of the time (similar to CGH).

However, while neck pain can be present, Migraine pain is not induced with neck movements or awkward postures. 164 165 166 167 Migraine symptoms will be worsened with general body movements (e.g. stair climbing) 168 not specifically head or neck movements.

While the pain location with Migraine has significant overlap with that of CGH, the epicenter of that pain is more typically anteriorly, particularly at onset. CHG, by contrast, always begins initially, in the occipital region (even in cases where the pain radiates or travels anteriorly). 169 170 171

Additionally, symptoms including nausea, vomiting, phonophobia and photophobia are uncommon in CGH. 172

Patients that suffer from CGH experience headaches more frequently than Migraine suffers, on average. 18 episodes/month (CGH) Vs. 7 episodes/month (Migraine). 173

* Note – Some various ‘types’ of HA can co-exist, making diagnosis tricky.174 One study found that 44% of HA sufferers experience more than one “headache form”. 175

Other Related phenomena

Tension-Type Headache

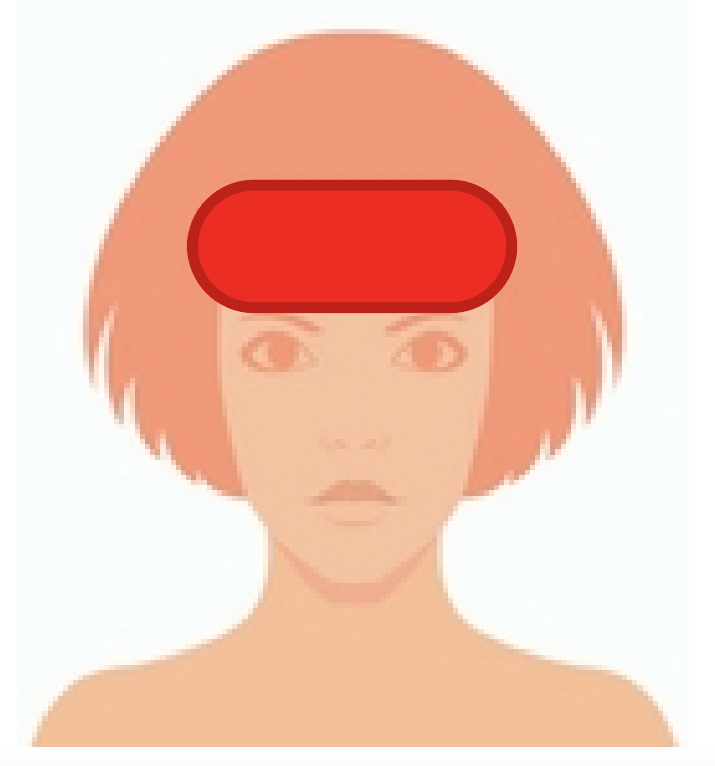

A Tension Headache (or “Stress Headache”) is usually described as a mild to moderate, diffuse pain that wraps around like a “tight band”.

A Tension Headache (or “Stress Headache”) is usually described as a mild to moderate, diffuse pain that wraps around like a “tight band”.

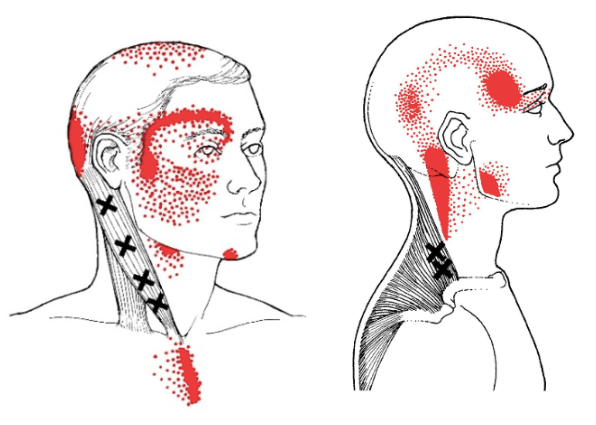

The upper cervical muscles may contribute to head pain as well through increased tone/contraction 176 177 178 179 180 or through the development of myofascial trigger points; 181 182 183 Some sources suggest that head pain derived from the myofascial structures (as opposed to the upper cervical joints) should be classified as “Tension-Type HA” 184 but this is not universally accepted.

Occipital Neuralgia

Occipital pain can arise from irritation of the Occipital Nerve, including compression of the Occipital nerve at the base of the skull, where it pierces through the cervical muscles to course up the back of the head/skull. This is considered a distinct entity, separate from CGH 185 186 although symptoms may overlap and these conditions can co-exist. Occipital Neuralgia (ON) typically results in intermittent stabbing, or searing pain at the base of the skull. 187 (Deep aching pain at the base of the skull is more likely a referral from the cervical spine, specifically C2 nerve).188 189

The phathogenesis of ON, from entrapment specifically, has been challenged. 190 191 192 193 194 195 196 197 198 However, occipital nerve pain clearly exists and can be a source of symptoms. A sub-occipital nerve block can help to diagnose (and treat) occipital neuralgia, 199 200 201 202 203 but not CGH. 204 205 206

While HA’s are annoying and, at times, debilitating, they are seldom indicative of serious pathology. Rare exceptions, however, do exist.

Seek Medical Attention with the following: 207 208

- Sudden onset of a new, severe headache

- A significant worsening of a preexisting headache in the absence of obvious predisposing factors

- Moderate or severe headache triggered by cough, exertion, or bearing down;

- New onset of a headache during or following pregnancy

- Headache onset after trauma

- Headache associated with fever, neck stiffness, skin rash, and with a history of cancer, HIV, or other systemic illness

- Headache associated with neurologic signs

- Headache triggered by changes in posture (eg. lying to sitting)

- New headache in patients over 50 years of age

Treatment of CGH

The first line of treatment for CGH is Physical Therapy; 209 “Physical Therapy is the preferred initial treatment because it is noninvasive.” 210 Ideally, with a therapist who has received advanced training in manual therapy and a comfort treating complex spine-related cases.

A 2013 systematic review 211 concluded that there is good quality evidence to support the use of joint manipulation & mobilization, as well as targeted cervical spine exercises, for treatment of CGH.

Stiffness, or hypomobility, of the joints in the upper cervical spine is a common finding in patients with CGH. Computer based techniques have found segmental hypomobility, most commonly in the upper 3 segments, in patients with a diagnosis of CGH. 212 213 These dysfunctional segments have been shown to refer pain to the head and face, with the most common joint being the C2/3 segment. 214 215 In the presence of these findings, cervical mobilization and manipulation are the prescribed treatment as multiple studies have demonstrated a positive effect on patients with CGH. 216 217 218 219

The musculature of the upper cervical spine may also be dysfunctional. Multiple studies have reported increased muscle tone / tightness, 220 221 222 223 224 225 226 as well as the presence of trigger points, in the cervical musculature in this population 227 228 229 230 231 232 – more so than in the general population, or in patients suffering from other types of HA.233 While the upper cervical joints may be the most frequent source of referred pain in patients with CGH, increased muscle tone/guarding in this region will place increased loads / strain to these structures and should be addressed in any comprehensive conservative treatment approach.

Also, trigger points in certain cervical muscles – such as the Sternocleidomastoid and Upper Trapezius muscles – have been shown to be capable of referring pain to the head and face. 234 Additionally, treatment to these trigger points has been shown, in randomized controlled trials, to be effective at reducing CGH.235

Additionally, studies have reported findings of impaired motor control of cervical stabilizing muscles and associated loss of postural alignment in patients with CGH.236 237 238 239 240 241 242 243 244 245 Studies have confirmed that these specific muscle deficits are unique to CGH and not typically present in patients with Migraine or tension-type HA.246

Specific exercises targeting specific cervical spine muscles have been shown to be effective at reducing pain and HA frequency.247 248 249

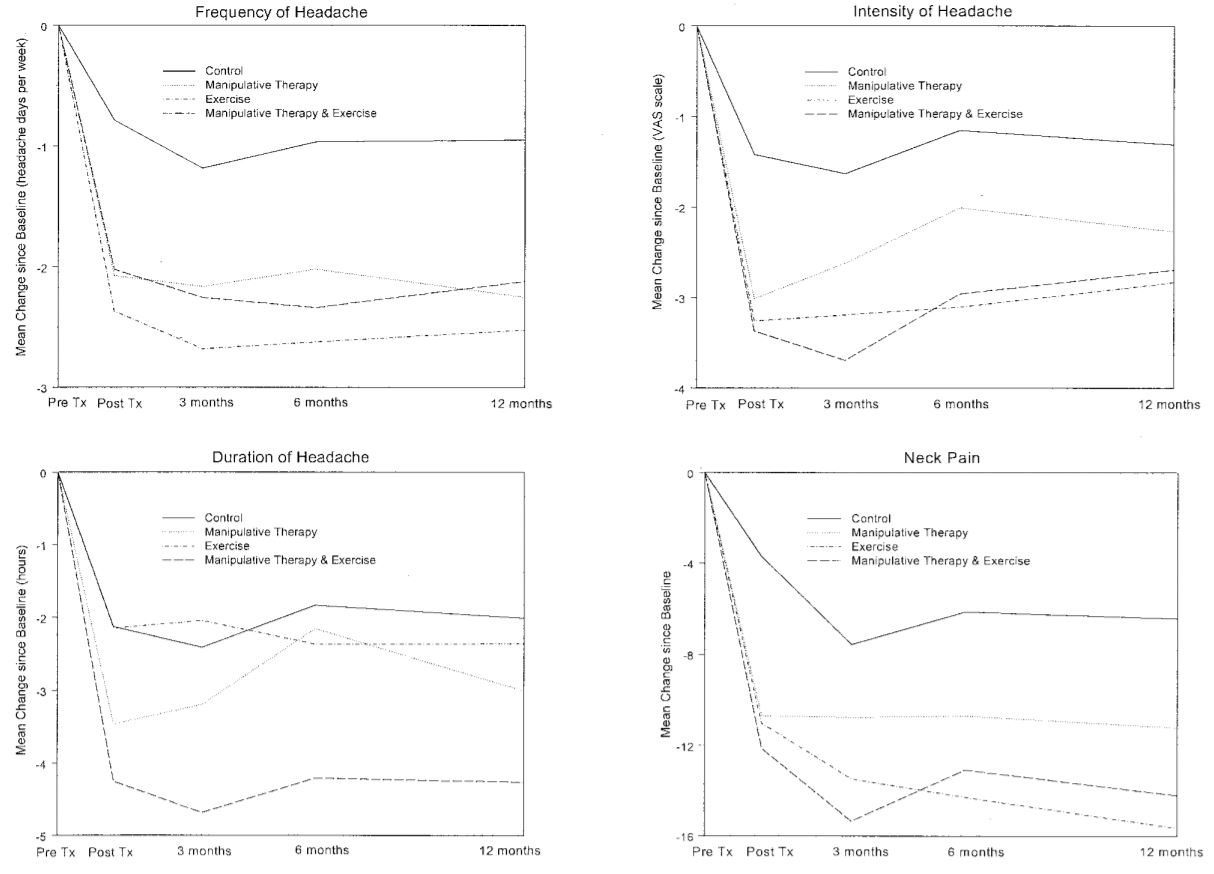

One randomized, controlled study investigating Manual Therapy (cervical mobilization and manipulation) and exercise achieved a > 50% decrease in HA frequency in 76% of patients at 7-week follow up. At that point, 35% of patients reported total relief. At 12 months, 72% had a >50% decrease in headache frequency, and 42% reported a 80-100% relief.250

One randomized, controlled study investigating Manual Therapy (cervical mobilization and manipulation) and exercise achieved a > 50% decrease in HA frequency in 76% of patients at 7-week follow up. At that point, 35% of patients reported total relief. At 12 months, 72% had a >50% decrease in headache frequency, and 42% reported a 80-100% relief.250

“This study showed that the conservative treatments of manipulative therapy and a specific exercise program are effective for the management of cervicogenic headache, and that the effects are maintained in the long term.”251

Clearly, in the hands of a good Physical Therapist is the place to be if you suffer from CHG!

Pharmacological Treatment

Evidence suggests that pharmacological therapy is generally not effective for treating CGH.252 Medications that are commonly used in treating other types of HAs (tricyclic antidepressants, gabapentin) are often “trialed” in patients with CGH. Given that their effectiveness has not been systematically studied for the treatment of CGH,253 and considering the adverse side-effects, pharmacological treatment should not be the first line of defense.

Other Interventions for CGH

Facet Joint Injections

Anesthetic injection of the upper cervical joints – C1/2, C2/3 and/or C3/4 – can provide temporary relief of Sx. 254 255 Guided anesthetic injections have been shown to mediate pain in patients with ‘dominant headaches’ with a ~60% effective rate.256 257 Patients with clinical findings of focal tenderness to palpation over the C2/3 joint were especially likely to experience a positive result with injection.258 Another study demonstrated ‘good’ to ‘excellent’ results in 61% of patients with CGH.259

It must be noted, that this relief is temporary. It is most useful for diagnostics and/or to allow for a window of opportunity for Physical Therapy interventions in cases where high irritability and symptom severity prevent hands on treatment and/or exercise.

Radiofrequency Neurotomy

Radiofrequency Neurotomy (RFN) is a process that utilizes heat generated by radio waves to interrupt the function of sensory nerves through ‘thermal denervation’.

“The rationale for this procedure is that if headaches can be relieved temporarily by controlled diagnostic blocks of the nerve (or nerves) that innervate a particular cervical joint, then interrupting the pain signal along that nerve, by coagulating it, should provide long-lasting relief.”260

RFN can be considered in cases where Physical Therapy has failed to help and an anesthetic injection at C2/3 or C3/4 has successfully provided pain relief (providing a high degree of diagnostic confidence).

While some studies show promising results,261 262 263 the evidence is still “limited and conflicting” 264 as other studies demonstrated RFN is not effective265 266 267 (although 2 of these studies did not target specific segments implicated by diagnostic injection, as is the standard).

A 2015 systematic review suggested that, while there is some evidence that RFN may offer potential benefit for CGH – this benefit has not been confirmed in adequate clinical trials. 268 “Current best evidence suggests that there is not sufficient evidence meeting the EBM [sic] criteria to support the use of RF facet denervation for cervicogenic headaches.”269

At best, RFN should only be considered in cases that prove to be intractable and unresponsive to conservative treatment; And when patients experience near complete (>90%) relief of symptoms with anesthetic injection

Glucocorticoid Injection

Glucocorticoids are corticosteroids that can be Injected directly into the cervical joints. While controlled trials for treating CGH are lacking, a couple of small studies have suggested somewhat positive results – mostly partial and temporary relief.270 271

Epidural steroid injections have also been studied, with some positive effects immediately and for a few weeks after. However, long-term results have failed to demonstrate a significant positive effect.272 273 274

Botox

The evidence suggests that injections with botulinum toxin is not effective. 275

Surgery

Surgical intervention for CGH is limited to cases of significant structural pathology including C2 spinal nerve compression/entrapment (69-72); C2/3 disc pathology (14); or upper cervical osteoarthritis. 276 277 278 Surgical options include a ‘decompression’ of the C2 nerve279 or a fusion (arthrodesis) of the upper cervical segments especially when the pain is arising from the C1/2 joint280 281 282 or a C2/3 IV Disc lesion.283

While the results can be effective in highly targeted cases, there are significant adverse effects to be considered with surgical intervention, including the possibility of intensification of pain over the long-term.284

Overall, surgical procedures are “not recommended unless there is compelling evidence of a surgically amenable lesion” causing the CGH and the patient’s symptoms are unresponsive to “all reasonable nonsurgical treatments.”285

Long story short, if you experience cervicogenic headaches – get yourself a good Physical Therapist!

At VASTA, our Physical Therapists have extensive advanced training including treatment of complex spine-related pain.

Click here to request an evaluation with one of our Expert Physical Therapists today.

Or call us directly at 802-399-2244

- Stovner, L. J., Hagen, K., Jensen, R., Katsarava, Z., Lipton, R. B., Scher, A. I., … & Zwart, J. A. (2007). The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia, 27(3), 193-210.

- Merskey, H. (1994). Classification of chronic pain. Description of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms, 1-213.

- Sjaastad, O., Fredriksen, T. A., & Pfaffenrath, V. (1998). Cervicogenic headache: diagnostic criteria. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 38(6), 442-445.

- Nilsson, N. (1995). The prevalence of cervicogenic headache in a random population sample of 20-59 year olds. Spine, 20(17), 1884-1888.

- Pearce, J. M. S. (1995). The importance of cervicogenic headache in the over-fifties. Headache Q Curr Treatment Res, 6, 293-296.

- Page, P. (2011). Cervicogenic headaches: an evidence-led approach to clinical management. International journal of sports physical therapy, 6(3), 254.

- Bajwa, Z. H., & Watson, J. C. (2016). Cervicogenic headache. Last updated May, 2018.

- Anthony, M. (2000). Cervicogenic headache: prevalence and response to local steroid therapy. Clinical and experimental Rheumatology, 18(2; SUPP/19), S-59.

- Nilsson, N. (1995). The prevalence of cervicogenic headache in a random population sample of 20-59 year olds. Spine, 20(17), 1884-1888.

- Pfaffenrath, V., & Kaube, H. (1990). Diagnostics of cervicogenic headache. Functional Neurology, 5(2), 159-164.

- Grimmer, K., Blizzard, L., & Dwyer, T. (1999). Frequency of headaches associated with the cervical spine and relationships with anthropometric, muscle performance, and recreational factors. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 80(5), 512-521.

- Evers, S. (2008). Comparison of cervicogenic headache with migraine. Cephalalgia, 28, 16-17.

- Lord, S. M., Barnsley, L., Wallis, B. J., & Bogduk, N. (1994). Third occipital nerve headache: a prevalence study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 57(10), 1187-1190.

- Sjaastad, O., Saunte, C., Hovdahl, H., Breivik, H., & Grønbâk, E. (1983). “Cervicogenic” headache. An hypothesis. Cephalalgia, 3(4), 249-256.

- Pöllmann, W., Keidel, M., & Pfaffenrath, V. (1997). Headache and the cervical spine: a critical review. Cephalalgia, 17(8), 801-816.

- Leone, M., D’amico, D., Grazzi, L., Attanasio, A., & Bussone, G. (1998). Cervicogenic headache: a critical review of the current diagnostic criteria. Pain, 78(1), 1-5.

- Blau, J. N., & MacGregor, E. A. (1994). Migraine and the neck. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 34(2), 88-90.

- Tfelt-Hansen, P., Lous, I., & Olesen, J. (1981). Prevalence and significance of muscle tenderness during common migraine attacks. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 21(2), 49-54.

- Kaniecki, R. G. (2002). Migraine and tension-type headache an assessment of challenges in diagnosis. Neurology, 58(9 suppl 6), S15-S20.

- Waelkens, J. (1985). Warning symptoms in migraine: characteristics and therapeutic implications. Cephalalgia, 5(4), 223-228.

- Fernández‐de‐las‐Peñas, C., Alonso‐Blanco, C., Cuadrado, M. L., Gerwin, R. D., & Pareja, J. A. (2006). Myofascial trigger points and their relationship to headache clinical parameters in chronic tension‐type headache. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 46(8), 1264-1272.

- Delfini, R., Salvati, M., Passacantilli, E., & Pacciani, E. (2000). Symptomatic cervicogenic headache. Clinical and experimental rheumatology, 18(2; SUPP/19), S-29.

- Mark, B. M. (1990). Cervicogenic headache differential diagnosis and clinical management: literature review. CRANIO, 8(4), 332-338.

- Packard, R. C. (1999). Epidemiology and pathogenesis of posttraumatic headache. The Journal of head trauma rehabilitation, 14(1), 9-21.

- Pearce, J. M. S. (1995). Cervicogenic headache: a personal view. Cephalalgia, 15(6), 463-469.

- The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edn. Cephalalgia 2004; 24 (suppl 1): 115–16.

- Bogduk, N., & Govind, J. (2009). Cervicogenic headache: an assessment of the evidence on clinical diagnosis, invasive tests, and treatment. The Lancet Neurology, 8(10), 959-968.

- Bogduk, N., & Govind, J. (2009). Cervicogenic headache: an assessment of the evidence on clinical diagnosis, invasive tests, and treatment. The Lancet Neurology, 8(10), 959-968.

- Lord, S. M., Barnsley, L., Wallis, B. J., & Bogduk, N. (1994). Third occipital nerve headache: a prevalence study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 57(10), 1187-1190.

- Cooper, G., Bailey, B., & Bogduk, N. (2007). Cervical zygapophysial joint pain maps. Pain Medicine, 8(4), 344-353.

- Dwyer, A., Aprill, C., & Bogduk, N. (1990). Cervical zygapophyseal joint pain patterns. I: A study in normal volunteers. Spine, 15(6), 453-457.

- Bogduk, N., & Marsland, A. (1988). The cervical zygapophysial joints as a source of neck pain. Spine, 13(6), 610-617.

- Bogduk, N., & Marsland, A. (1986). On the concept of third occipital headache. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 49(7), 775-780.

- Dwyer, A., Aprill, C., & Bogduk, N. (1990). Cervical zygapophyseal joint pain patterns. I: A study in normal volunteers. Spine, 15(6), 453-457.

- Dreyfuss, P., Michaelsen, M., & Fletcher, D. (1994). Atlanto-occipital and lateral atlanto-axial joint pain patterns. Spine, 19(10), 1125-1131.

- Jull, G., Amiri, M., Bullock-Saxton, J., Darnell, R., & Lander, C. (2007). Cervical musculoskeletal impairment in frequent intermittent headache. Part 1: Subjects with single headaches. Cephalalgia, 27(7), 793-802.

- Zito, G., Jull, G., & Story, I. (2006). Clinical tests of musculoskeletal dysfunction in the diagnosis of cervicogenic headache. Manual therapy, 11(2), 118-129.

- Jull, G., Barrett, C., Magee, R., & Ho, P. (1999). Further clinical clarification of the muscle dysfunction in cervical headache. Cephalalgia, 19(3), 179-185.

- Watson, D. H., & Trott, P. H. (1993). Cervical headache: an investigation of natural head posture and upper cervical flexor muscle performance. Cephalalgia, 13(4), 272-284.

- Bodes-Pardo, G., Pecos-Martín, D., Gallego-Izquierdo, T., Salom-Moreno, J., Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C., & Ortega-Santiago, R. (2013). Manual treatment for cervicogenic headache and active trigger point in the sternocleidomastoid muscle: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics, 36(7), 403-411.

- Huber, J., Lisiński, P., & Polowczyk, A. (2013). Reinvestigation of the dysfunction in neck and shoulder girdle muscles as the reason of cervicogenic headache among office workers. Disability and rehabilitation, 35(10), 793-802.

- Suijlekom, H. A. V., Lamé, I., Stomp‐van den Berg, S. G., Kessels, A. G., & Weber, W. E. (2003). Quality of Life of Patients With Cervicogenic Headache: A Comparison With Control Subjects and Patients With Migraine or Tension‐type Headache. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 43(10), 1034-1041.

- Anthony, M. (2000). Cervicogenic headache: prevalence and response to local steroid therapy. Clinical and experimental Rheumatology, 18(2; SUPP/19), S-59.

- Alix, M. E., & Bates, D. K. (1999). A proposed etiology of cervicogenic headache: the neurophysiologic basis and anatomic relationship between the dura mater and the rectus posterior capitis minor muscle. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics, 22(8), 534-539.

- Anthony, M. (1992). Headache and the greater occipital nerve. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery, 94(4), 297-301.

- Bogduk N, Corrigan B, Kelly P et al. (1985) Cervical headache. Med J Aust; 143:202, 206-207.

- Bogduk, N. (1992). The anatomical basis for cervicogenic headache. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics, 15(1), 67-70.

- Bogduk, N., & Marsland, A. (1986). On the concept of third occipital headache. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 49(7), 775-780.

- Bogduk, N. (1984). Headaches and the cervical spine. An editorial.

- Bogduk, N. (1980). The anatomy of occipital neuralgia. Clin Exp Neurol, 17, 167-184.

- Kerr, F. W. (1961). Structural relation of the trigeminal spinal tract to upper cervical roots and the solitary nucleus in the cat. Experimental neurology, 4(2), 134-148.

- Kerr, F. W. (1961). A mechanism to account for frontal headache in cases of posterior-fossa tumors. Journal of neurosurgery, 18(5), 605-609.

- Bogduk, N. (2004). The neck and headaches. Neurologic clinics, 22(1), 151-171.

- Bogduk, N., Bartsch, T. (2008) Cervicogenic headache. In: Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Dodick DW, eds. Wolff ’s Headache, 8th edn. Oxford University Press, 551–70.

- Bogduk, N., & Govind, J. (2009). Cervicogenic headache: an assessment of the evidence on clinical diagnosis, invasive tests, and treatment. The Lancet Neurology, 8(10), 959-968.

- Bajwa, Z. H., & Watson, J. C. (2016). Cervicogenic headache. Last updated May, 2018.

- Goodman, C., & Fuller, K. (2009). Pathology Implications for the Physical Therapist (3rdedn) St. Louis: Saunders, 2009, 625-626.

- Jull, G. A., & Stanton, W. R. (2005). Predictors of responsiveness to physiotherapy management of cervicogenic headache. Cephalalgia, 25(2), 101-108.

- Haas, M., Spegman, A., Peterson, D., Aickin, M., & Vavrek, D. (2010). Dose response and efficacy of spinal manipulation for chronic cervicogenic headache: a pilot randomized controlled trial. The spine journal, 10(2), 117-128.

- Bogduk, N., Bartsch, T. (2008) Cervicogenic headache. In: Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Dodick DW, eds. Wolff ’s Headache, 8th edn. Oxford University Press, 551–70.

- Bogduk, N. (2001). Cervicogenic headache: anatomic basis and pathophysiologic mechanisms. Current pain and headache reports, 5(4), 382-386.

- Bartsch, T., & Goadsby, P. J. (2002). Stimulation of the greater occipital nerve induces increased central excitability of dural afferent input. Brain, 125(7), 1496-1509.

- Bartsch, T., & Goadsby, P. J. (2003). Increased responses in trigeminocervical nociceptive neurons to cervical input after stimulation of the dura mater. Brain, 126(8), 1801-1813.

- Goadsby, P. J., & Bartsch, T. (2008). Introduction: On the functional neuroanatomy of neck pain. Cephalagia, 28 (Suppl. 1), 1-7

- Dwyer, A., Aprill, C., & Bogduk, N. (1990). Cervical zygapophyseal joint pain patterns. I: A study in normal volunteers. Spine, 15(6), 453-457.

- Dreyfuss, P., Michaelsen, M., & Fletcher, D. (1994). Atlanto-occipital and lateral atlanto-axial joint pain patterns. Spine, 19(10), 1125-1131.

- Bogduk, N., & Govind, J. (2009). Cervicogenic headache: an assessment of the evidence on clinical diagnosis, invasive tests, and treatment. The Lancet Neurology, 8(10), 959-968.

- Lord, S. M., Barnsley, L., Wallis, B. J., & Bogduk, N. (1994). Third occipital nerve headache: a prevalence study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 57(10), 1187-1190.

- Cooper, G., Bailey, B., & Bogduk, N. (2007). Cervical zygapophysial joint pain maps. Pain Medicine, 8(4), 344-353.

- Dwyer, A., Aprill, C., & Bogduk, N. (1990). Cervical zygapophyseal joint pain patterns. I: A study in normal volunteers. Spine, 15(6), 453-457.

- Bogduk, N., & Marsland, A. (1988). The cervical zygapophysial joints as a source of neck pain. Spine, 13(6), 610-617.

- Bogduk, N., & Marsland, A. (1986). On the concept of third occipital headache. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 49(7), 775-780.

- Dwyer, A., Aprill, C., & Bogduk, N. (1990). Cervical zygapophyseal joint pain patterns. I: A study in normal volunteers. Spine, 15(6), 453-457.

- Cooper, G., Bailey, B., & Bogduk, N. (2007). Cervical zygapophysial joint pain maps. Pain Medicine, 8(4), 344-353.

- Lord, S. M., Barnsley, L., Wallis, B. J., & Bogduk, N. (1994). Third occipital nerve headache: a prevalence study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 57(10), 1187-1190.

- Bogduk, N., & Marsland, A. (1986). On the concept of third occipital headache. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 49(7), 775-780.

- Bogduk, N., & Marsland, A. (1988). The cervical zygapophysial joints as a source of neck pain. Spine, 13(6), 610-617.

- Lord, S. M., Barnsley, L., Wallis, B. J., & Bogduk, N. (1994). Third occipital nerve headache: a prevalence study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 57(10), 1187-1190.

- Bogduk, N., & Govind, J. (2009). Cervicogenic headache: an assessment of the evidence on clinical diagnosis, invasive tests, and treatment. The Lancet Neurology, 8(10), 959-968.

- Dwyer, A., Aprill, C., & Bogduk, N. (1990). Cervical zygapophyseal joint pain patterns. I: A study in normal volunteers. Spine, 15(6), 453-457.

- Dreyfuss, P., Michaelsen, M., & Fletcher, D. (1994). Atlanto-occipital and lateral atlanto-axial joint pain patterns. Spine, 19(10), 1125-1131.

- Dwyer, A., Aprill, C., & Bogduk, N. (1990). Cervical zygapophyseal joint pain patterns. I: A study in normal volunteers. Spine, 15(6), 453-457.

- McCormick, C. C. (1987). Arthrography of the atlanto-axial (C1-C2) joints: Technique and results. J Intervent Radiol, 2(9).

- Cooper, G., Bailey, B., & Bogduk, N. (2007). Cervical zygapophysial joint pain maps. Pain Medicine, 8(4), 344-353.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. (1988). Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Cephalalgia, 8(7), 1-96.

- Bodes-Pardo, G., Pecos-Martín, D., Gallego-Izquierdo, T., Salom-Moreno, J., Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C., & Ortega-Santiago, R. (2013). Manual treatment for cervicogenic headache and active trigger point in the sternocleidomastoid muscle: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics, 36(7), 403-411.

- Huber, J., Lisiński, P., & Polowczyk, A. (2013). Reinvestigation of the dysfunction in neck and shoulder girdle muscles as the reason of cervicogenic headache among office workers. Disability and rehabilitation, 35(10), 793-802.

- The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edn. Cephalalgia 2004; 24 (suppl 1): 115–16.

- Schellhas, K. P., Smith, M. D., Gundry, C. R., & Pollei, S. R. (1996). Cervical discogenic pain: prospective correlation of magnetic resonance imaging and discography in asymptomatic subjects and pain sufferers. Spine, 21(3), 300-311.

- Grubb, S. A., & Kelly, C. K. (2000). Cervical Discography:: Clinical Implications From 12 Years of Experience. Spine, 25(11), 1382-1389.

- Slipman, C. W., Lipetz, J. S., Jackson, H. B., Plastaras, C. T., & Vresilovic, E. J. (2001). Outcomes of therapeutic selective nerve root blocks for whiplash induced cervical radicular pain. Pain Physician, 4(2), 167-174.

- Slipman, C. W., Patel, R. K., Zhang, L., Vresilovic, E., Lenrow, D., Shin, C., & Herzog, R. (2001). Side of symptomatic annular tear and site of low back pain: is there a correlation?. Spine, 26(8), E165-E168.

- Schellhas, K. P., Smith, M. D., Gundry, C. R., & Pollei, S. R. (1996). Cervical discogenic pain: prospective correlation of magnetic resonance imaging and discography in asymptomatic subjects and pain sufferers. Spine, 21(3), 300-311.

- Grubb, S. A., & Kelly, C. K. (2000). Cervical Discography: Clinical Implications From 12 Years of Experience. Spine, 25(11), 1382-1389.

- Schofferman, J., Garges, K., Goldthwaite, N., Koestler, M., & Libby, E. (2002). Upper cervical anterior diskectomy and fusion improves discogenic cervical headaches. Spine, 27(20), 2240-2244.

- Cooper, G., Bailey, B., & Bogduk, N. (2007). Cervical zygapophysial joint pain maps. Pain Medicine, 8(4), 344-353.

- Schofferman, J., Garges, K., Goldthwaite, N., Koestler, M., & Libby, E. (2002). Upper cervical anterior diskectomy and fusion improves discogenic cervical headaches. Spine, 27(20), 2240-2244.

- Park, S. W., Park, Y. S., Nam, T. K., & Cho, T. G. (2011). The effect of radiofrequency neurotomy of lower cervical medial branches on cervicogenic headache. Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society, 50(6), 507.

- Jansen, J. (2008). Surgical treatment of cervicogenic headache. Cephalalgia, 28(1_suppl), 41-44.

- Diener, H. C., Kaminski, M., Stappert, G., Stolke, D., & Schoch, B. (2007). Lower cervical disc prolapse may cause cervicogenic headache: prospective study in patients undergoing surgery. Cephalalgia, 27(9), 1050-1054.

- Bogduk, N., & Govind, J. (2009). Cervicogenic headache: an assessment of the evidence on clinical diagnosis, invasive tests, and treatment. The Lancet Neurology, 8(10), 959-968.

- Amevo, B., Aprill, C., & Bogduk, N. (1992). Abnormal instantaneous axes of rotation in patients with neck pain. Spine, 17(7), 748-756.

- Bogduk, N., & Govind, J. (2009). Cervicogenic headache: an assessment of the evidence on clinical diagnosis, invasive tests, and treatment. The Lancet Neurology, 8(10), 959-968.

- Van Suijlekom, J. A., De Vet, H. C. W., Van den Berg, S. G. M., & Weber, W. E. J. (1999). Interobserver reliability of diagnostic criteria for cervicogenic headache. Cephalalgia, 19(9), 817-823.

- Van Suijlekom, H. A., De Vet, H. C., Van Den Berg, S. G., & Weber, W. E. (2000). Interobserver reliability in physical examination of the cervical spine in patients with headache. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 40(7), 581-586.

- Bovim, G. (1992). Cervicogenic headache, migraine, and tension-type headache. Pressure-pain threshold measurements. Pain, 51(2), 169-173.

- Sjaastad, O., Saunte, C., Hovdahl, H., Breivik, H., & Grønbâk, E. (1983). “Cervicogenic” headache. An hypothesis. Cephalalgia, 3(4), 249-256.

- Pöllmann, W., Keidel, M., & Pfaffenrath, V. (1997). Headache and the cervical spine: a critical review. Cephalalgia, 17(8), 801-816.

- Sjaastad, O., Fredriksen, T. A., & Pfaffenrath, V. (1990). Cervicogenic headache: diagnostic criteria. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 30(11), 725-726.

- Sjaastad, O., Fredriksen, T. A., & Pfaffenrath, V. (1998). Cervicogenic headache: diagnostic criteria. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 38(6), 442-445.

- Van Suijlekom, J. A., De Vet, H. C. W., Van den Berg, S. G. M., & Weber, W. E. J. (1999). Interobserver reliability of diagnostic criteria for cervicogenic headache. Cephalalgia, 19(9), 817-823.

- Van Suijlekom, H. A., De Vet, H. C., Van Den Berg, S. G., & Weber, W. E. (2000). Interobserver reliability in physical examination of the cervical spine in patients with headache. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 40(7), 581-586.

- Bovim, G. (1992). Cervicogenic headache, migraine, and tension-type headache. Pressure-pain threshold measurements. Pain, 51(2), 169-173.

- D’Amico, D., Leone, M., & Bussone, G. (1994). Side‐locked unilaterality and pain localization in long‐lasting headaches: migraine, tension‐type headache, and cervicogenic headache. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 34(9), 526-530.

- Leone, M., D’Amico, D., Moschiano, F., Farinotti, M., Filippini, G., & Bussone, G. (1995). Possible identification of cervicogenic headache among patients with migraine: an analysis of 374 headaches. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 35(8), 461-464.

- Leone, M., D’amico, D., Grazzi, L., Attanasio, A., & Bussone, G. (1998). Cervicogenic headache: a critical review of the current diagnostic criteria. Pain, 78(1), 1-5.

- Van Suijlekom, J. A., De Vet, H. C. W., Van den Berg, S. G. M., & Weber, W. E. J. (1999). Interobserver reliability of diagnostic criteria for cervicogenic headache. Cephalalgia, 19(9), 817-823.

- Van Suijlekom, H. A., De Vet, H. C., Van Den Berg, S. G., & Weber, W. E. (2000). Interobserver reliability in physical examination of the cervical spine in patients with headache. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 40(7), 581-586.

- Sjaastad, O., Fredriksen, T. A., & Pfaffenrath, V. (1990). Cervicogenic headache: diagnostic criteria. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 30(11), 725-726.

- Jull, G., Amiri, M., Bullock-Saxton, J., Darnell, R., & Lander, C. (2007). Cervical musculoskeletal impairment in frequent intermittent headache. Part 1: Subjects with single headaches. Cephalalgia, 27(7), 793-802.

- Zito, G., Jull, G., & Story, I. (2006). Clinical tests of musculoskeletal dysfunction in the diagnosis of cervicogenic headache. Manual therapy, 11(2), 118-129.

- Zwart, J. A. (1997). Neck mobility in different headache disorders. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 37(1), 6-11.

- Ogince, M., Hall, T., Robinson, K., & Blackmore, A. M. (2007). The diagnostic validity of the cervical flexion–rotation test in C1/2-related cervicogenic headache. Manual therapy, 12(3), 256-262.

- Hall, T. M., Robinson, K. W., Fujinawa, O., Akasaka, K., & Pyne, E. A. (2008). Intertester reliability and diagnostic validity of the cervical flexion-rotation test. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics, 31(4), 293-300.

- Bogduk, N. (2005). Distinguishing primary headache disorders from cervicogenic headache: clinical and therapeutic implications. Headache Currents, 2(2), 27-36.

- Zwart, J. A. (1997). Neck mobility in different headache disorders. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 37(1), 6-11.

- Bogduk, N. (2004). The neck and headaches. Neurologic clinics, 22(1), 151-171.

- Jull, G., Amiri, M., Bullock-Saxton, J., Darnell, R., & Lander, C. (2007). Cervical musculoskeletal impairment in frequent intermittent headache. Part 1: Subjects with single headaches. Cephalalgia, 27(7), 793-802.

- Jull, G., Amiri, M., Bullock-Saxton, J., Darnell, R., & Lander, C. (2007). Cervical musculoskeletal impairment in frequent intermittent headache. Part 1: Subjects with single headaches. Cephalalgia, 27(7), 793-802.

- Antonaci, F., Ghirmai, S., Bono, G., Sandrini, G., & Nappi, G. (2001). Cervicogenic headache: evaluation of the original diagnostic criteria. Cephalalgia, 21(5), 573-583.

- Fredriksen, T. A., Fougner, R., Tangerud, Å., & Sjaastad, O. (1989). Cervicogenic headache. Radiological investigations concerning head/neck. Cephalalgia, 9(2), 139-146.

- Knackstedt, H., Kråkenes, J., Bansevicius, D., & Russell, M. B. (2012). Magnetic resonance imaging of craniovertebral structures: clinical significance in cervicogenic headaches. The journal of headache and pain, 13(1), 39-44.

- Pfaffenrath, V., Dandekar, R., & Pöllmann, W. (1987). Cervicogenic headache‐the clinical picture, radiological findings and hypotheses on its pathophysiology. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 27(9), 495-499.

- Bogduk, N., Bartsch, T. (2008) Cervicogenic headache. In: Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Dodick DW, eds. Wolff ’s Headache, 8th edn. Oxford University Press, 551–70.

- Zwart, J. A. (1997). Neck mobility in different headache disorders. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 37(1), 6-11.

- Lord, S. M., Barnsley, L., Wallis, B. J., & Bogduk, N. (1994). Third occipital nerve headache: a prevalence study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 57(10), 1187-1190.

- Sjaastad, O., Saunte, C., Hovdahl, H., Breivik, H., & Grønbâk, E. (1983). “Cervicogenic” headache. An hypothesis. Cephalalgia, 3(4), 249-256.

- Sjaastad, O., & Fredriksen, T. A. (2000). Cervicogenic headache: criteria, classification and epidemiology. Clinical and experimental rheumatology, 18(2; SUPP/19), S-3.

- Sjaastad, O., Fredriksen, T. A., & Pfaffenrath, V. (1998). Cervicogenic headache: diagnostic criteria. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 38(6), 442-445.

- Olesen, J. (2018). Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, Asbtracts. Cephalalgia, 38(1), 1-211.

- Antonaci, F., Bono, G., & Chimento, P. (2006). Diagnosing cervicogenic headache. The journal of headache and pain, 7(3), 145-148.

- Jansen, J., & Sjaastad, O. (2006). Cervicogenic Headache: Sith/Robinson Approach in Bilateral Cases. Functional neurology, 21(4), 205-210.

- Bovim, G. (1992). Cervicogenic headache, migraine, and tension-type headache. Pressure-pain threshold measurements. Pain, 51(2), 169-173.

- The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edn. Cephalalgia 2004; 24 (suppl 1): 115–16.

- The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edn. Cephalalgia 2004; 24 (suppl 1): 115–16.

- Bovim, G. (1992). Cervicogenic headache, migraine, and tension-type headache. Pressure-pain threshold measurements. Pain, 51(2), 169-173.

- Van Suijlekom, J. A., De Vet, H. C. W., Van den Berg, S. G. M., & Weber, W. E. J. (1999). Interobserver reliability of diagnostic criteria for cervicogenic headache. Cephalalgia, 19(9), 817-823.

- Van Suijlekom, H. A., De Vet, H. C., Van Den Berg, S. G., & Weber, W. E. (2000). Interobserver reliability in physical examination of the cervical spine in patients with headache. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 40(7), 581-586.

- Zito, G., Jull, G., & Story, I. (2006). Clinical tests of musculoskeletal dysfunction in the diagnosis of cervicogenic headache. Manual therapy, 11(2), 118-129.

- Sandmark, H., & Nisell, R. (1995). Validity of five common manual neck pain provoking tests. Scandinavian journal of rehabilitation medicine, 27(3), 131-136.

- Jull, G., Bogduk, N., & Márslañd, A. (1988). The accuracy of manual diagnosis for cervical zygapophysial joint pain syndromes. The Medical Journal of Australia, 148(5), 233-236.

- Jull, G., Zito, G., Trott, P., Potter, H., Shirley, D., & Richardson, C. (1997). Inter-examiner reliability to detect painful upper cervical joint dysfunction. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 43(2), 125-129.

- Hall, T., Briffa, K., & Hopper, D. (2008). Clinical evaluation of cervicogenic headache: a clinical perspective. Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy, 16(2), 73-80.

- DvorÁk, J., Herdmann, J., Janssen, B., Theiler, R., & Grob, D. (1990). Motor-evoked potentials in patients with cervical spine disorders. Spine, 15(10), 1013-1016.

- Chou, L. H., & Lenrow, D. A. (2002). Cervicogenic headache. Pain physician, 5(2), 215-225.

- Bogduk, N., & Govind, J. (2009). Cervicogenic headache: an assessment of the evidence on clinical diagnosis, invasive tests, and treatment. The Lancet Neurology, 8(10), 959-968.

- Bajwa, Z. H., & Watson, J. C. (2016). Cervicogenic headache. Last updated May, 2018.

- Blau, J. N., & MacGregor, E. A. (1994). Migraine and the neck. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 34(2), 88-90.

- Tfelt-Hansen, P., Lous, I., & Olesen, J. (1981). Prevalence and significance of muscle tenderness during common migraine attacks. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 21(2), 49-54.

- Kaniecki, R. G. (2002). Migraine and tension-type headache an assessment of challenges in diagnosis. Neurology, 58(9 suppl 6), S15-S20.

- Waelkens, J. (1985). Warning symptoms in migraine: characteristics and therapeutic implications. Cephalalgia, 5(4), 223-228.

- Blau, J. N., & MacGregor, E. A. (1994). Migraine and the neck. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 34(2), 88-90.

- Kaniecki, R. G. (2002). Migraine and tension-type headache an assessment of challenges in diagnosis. Neurology, 58(9 suppl 6), S15-S20.

- Mark, B. M. (1990). Cervicogenic headache differential diagnosis and clinical management: literature review. CRANIO, 8(4), 332-338.

- Sjaastad, O., Bovim, G., & Stovner, L. J. (1992). Laterality of pain and other migraine criteria in common migraine. A comparison with cervicogenic headache. Functional neurology, 7(4), 289-294.

- Sjaastad, O., & Bovim, G. (1991). Cervicogenic headache. The differentiation from common migraine. An overview. Functional neurology, 6(2), 93-100.

- Sjaastad, O. (1990). The headache of challenge in our time: cervicogenic headache. Functional neurology, 5(2), 155-158.

- The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edn. Cephalalgia 2004; 24 (suppl 1): 115–16.

- D’Amico, D., Leone, M., & Bussone, G. (1994). Side‐locked unilaterality and pain localization in long‐lasting headaches: migraine, tension‐type headache, and cervicogenic headache. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 34(9), 526-530.

- Leone, M., D’Amico, D., Moschiano, F., Farinotti, M., Filippini, G., & Bussone, G. (1995). Possible identification of cervicogenic headache among patients with migraine: an analysis of 374 headaches. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 35(8), 461-464.

- Leone, M., D’amico, D., Grazzi, L., Attanasio, A., & Bussone, G. (1998). Cervicogenic headache: a critical review of the current diagnostic criteria. Pain, 78(1), 1-5.

- Fredriksen, T. A., Hovdal, H., & Sjaastad, O. (1987). “Cervicogenic headache”: clinical manifestation. Cephalalgia, 7(2), 147-160.

- Anthony, M. (2000). Cervicogenic headache: prevalence and response to local steroid therapy. Clinical and experimental Rheumatology, 18(2; SUPP/19), S-59.

- Fishbain, D. A., Cutler, R., Cole, B., Rosomoff, H. L., & Rosomoff, R. S. (2001). International Headache Society headache diagnostic patterns in pain facility patients. The Clinical journal of pain, 17(1), 78-93.

- Amiri, M., Jull, G., Bullock-Saxton, J., Darnell, R., & Lander, C. (2007). Cervical musculoskeletal impairment in frequent intermittent headache. Part 2: subjects with concurrent headache types. Cephalalgia, 27(8), 891-898.

- Iansek, R., Heywood, J., Karnaghan, J., & Balla, J. I. (1987). Cervical spondylosis and headaches. Clinical and experimental neurology, 23, 175-178.

- Jull, G., Amiri, M., Bullock-Saxton, J., Darnell, R., & Lander, C. (2007). Cervical musculoskeletal impairment in frequent intermittent headache. Part 1: Subjects with single headaches. Cephalalgia, 27(7), 793-802.

- Zito, G., Jull, G., & Story, I. (2006). Clinical tests of musculoskeletal dysfunction in the diagnosis of cervicogenic headache. Manual therapy, 11(2), 118-129.

- Jull, G., Barrett, C., Magee, R., & Ho, P. (1999). Further clinical clarification of the muscle dysfunction in cervical headache. Cephalalgia, 19(3), 179-185.

- Watson, D. H., & Trott, P. H. (1993). Cervical headache: an investigation of natural head posture and upper cervical flexor muscle performance. Cephalalgia, 13(4), 272-284.

- Travell JG, Simons DG. (1983) The upper extremities. In Myofascial pain and dysfunction: The trigger point manual. Volume 1: Williams & Wilkins, pp 165-330.

- Bodes-Pardo, G., Pecos-Martín, D., Gallego-Izquierdo, T., Salom-Moreno, J., Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C., & Ortega-Santiago, R. (2013). Manual treatment for cervicogenic headache and active trigger point in the sternocleidomastoid muscle: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics, 36(7), 403-411.

- Huber, J., Lisiński, P., & Polowczyk, A. (2013). Reinvestigation of the dysfunction in neck and shoulder girdle muscles as the reason of cervicogenic headache among office workers. Disability and rehabilitation, 35(10), 793-802.

- Olesen, J. (2018). Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, Asbtracts. Cephalalgia, 38(1), 1-211.

- Bogduk, N., & Govind, J. (2009). Cervicogenic headache: an assessment of the evidence on clinical diagnosis, invasive tests, and treatment. The Lancet Neurology, 8(10), 959-968.

- Olesen, J. (2018). Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, Asbtracts. Cephalalgia, 38(1), 1-211.

- Bajwa, Z. H., & Watson, J. C. (2016). Cervicogenic headache. Last updated May, 2018.

- The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edn. Cephalalgia 2004; 24 (suppl 1): 115–16.

- Bogduk, N. (2001). Cervicogenic headache: anatomic basis and pathophysiologic mechanisms. Current pain and headache reports, 5(4), 382-386.

- Bovim, G., Bonamico, L., Fredriksen, T. A., Lindboe, C. F., Stolt-Nielsen, A. N. D. R. E. A. S., & Sjaastad, O. (1991). Topographic variations in the peripheral course of the greater occipital nerve. Autopsy study with clinical correlations. Spine, 16(4), 475-478.

- Hammond, S. R., & Danta, G. (1978). Occipital neuralgia. Clinical and experimental neurology, 15, 258-270.

- Schultz DR. Occipital neuralgia. J Am Osteopath Ass 1977; 76: 335-343.

- Bogduk, N. (1982). The clinical anatomy of the cervical dorsal rami. Spine, 7(4), 319-330.

- Bogduk, N., Bartsch, T. (2008) Cervicogenic headache. In: Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Dodick DW, eds. Wolff ’s Headache, 8th edn. Oxford University Press, 551–70.

- Hunter, C. R., & Mayfield, F. H. (1949). Role of the upper cervical roots in the production of pain in the head. The American Journal of Surgery, 78(5), 743-751.

- Mayfield, F. H. (1955). Cervical trauma. Neurosurgical aspects. Clin Neurosurg, 2, 83-100.

- Bogduk, N. (1980). The anatomy of occipital neuralgia. Clin Exp Neurol, 17, 167-184.

- Bovim, G., Fredriksen, T. A., Stolt‐Nielsen, A., & Sjaastad, O. (1992). Neurolysis of the greater occipital nerve in cervicogenic headache. A follow up study. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 32(4), 175-179.

- Bogduk, N., & Govind, J. (2009). Cervicogenic headache: an assessment of the evidence on clinical diagnosis, invasive tests, and treatment. The Lancet Neurology, 8(10), 959-968.

- Anthony, M. (2000). Cervicogenic headache: prevalence and response to local steroid therapy. Clinical and experimental Rheumatology, 18(2; SUPP/19), S-59.

- Sluijter, M. E., Dingemans, W., & Barendse, G. (1992). Occipital nerve block in the management of headache and cervical pain. Cephalalgia, 12(5), 325-326.

- Gawel, M. J., & Rothbart, P. J. (1992). Occipital nerve block in the management of headache and cervical pain. Cephalalgia, 12(1), 9-13.

- Vincent, M. B., LUNA, R. A., SCANDIUZZI, D., & NOVIS, S. A. (1998). Greater occipital nerve blockade in cervicogenic headache. Arquivos de neuro-psiquiatria, 56(4), 720-725.

- Afridi, S. K., Shields, K. G., Bhola, R., & Goadsby, P. J. (2006). Greater occipital nerve injection in primary headache syndromes–prolonged effects from a single injection. Pain, 122(1-2), 126-129.

- Goadsby, P. J., Lipton, R. B., & Ferrari, M. D. (2002). Migraine, current understanding and treatment. New England journal of medicine, 346(4), 257-270.

- Leone, M., Cecchini, A. P., Mea, E., Tulio, V., & Bussone, G. (2008). Epidemiology of fixed unilateral headaches. Cephalalgia, 28(1_suppl), 8-11.

- Cleland, J. A., Mintken, P. E., Carpenter, K., Fritz, J. M., Glynn, P., Whitman, J., & Childs, J. D. (2010). Examination of a clinical prediction rule to identify patients with neck pain likely to benefit from thoracic spine thrust manipulation and a general cervical range of motion exercise: multi-center randomized clinical trial. Physical therapy, 90(9), 1239-1250.

- De Hertogh, W., Vaes, P., & Versijpt, J. (2013). Diagnostic work-up of an elderly patient with unilateral head and neck pain. A case report. Manual therapy, 18(6), 598-601.

- Pöllmann, W., Keidel, M., & Pfaffenrath, V. (1997). Headache and the cervical spine: a critical review. Cephalalgia, 17(8), 801-816.

- Bajwa, Z. H., & Watson, J. C. (2016). Cervicogenic headache. Last updated May, 2018.

- Racicki, S., Gerwin, S., DiClaudio, S., Reinmann, S., & Donaldson, M. (2013). Conservative physical therapy management for the treatment of cervicogenic headache: a systematic review. Journal of manual & manipulative therapy, 21(2), 113-124.

- Pfaffenrath, V., Dandekar, R., Mayer, E. T. H., Hermann, G., & Pöllmann, W. (1988). Cervicogenic headache: results of computer-based measurements of cervical spine mobility in 15 patients. Cephalalgia, 8(1), 45-48.

- Jensen, O. K., Justesen, T., Nielsen, F. F., & Brixen, K. (1990). Functional radiographic examination of the cervical spine in patients with post-traumatic headache. Cephalalgia, 10(6), 295-303.

- Meloche, J. P., Bergeron, Y., Bellavance, A., Morand, M., Huot, J., & Belzile, G. (1993). Painful intervertebral dysfunction: Robert Maigne’s original contribution to headache of cervical origin. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 33(6), 328-334.

- Jull, G. (1985). Manual diagnosis of C2-3 headache. Cephalalgia, 5(3_suppl), 308-309.

- Hurwitz, E. L., Aker, P. D., Adams, A. H., Meeker, W. C., & Shekelle, P. G. (1996). Manipulation and mobilization of the cervical spine: a systematic review of the literature. Spine, 21(15), 1746-1759.

- Schoensee, S. K., Jensen, G., Nicholson, G., Gossman, M., & Katholi, C. (1995). The effect of mobilization on cervical headaches. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 21(4), 184-196.

- Jensen, O. K., Nielsen, F. F., & Vosmar, L. (1990). An open study comparing manual therapy with the use of cold packs in the treatment of post-traumatic headache. Cephalalgia, 10(5), 241-250.

- Jull, G., Trott, P., Potter, H., Zito, G., Niere, K., Shirley, D., … & Richardson, C. (2002). A randomized controlled trial of exercise and manipulative therapy for cervicogenic headache. Spine, 27(17), 1835-1843.

- Zito, G., Jull, G., & Story, I. (2006). Clinical tests of musculoskeletal dysfunction in the diagnosis of cervicogenic headache. Manual therapy, 11(2), 118-129.

- Jull, G., Bogduk, N., & Márslañd, A. (1988). The accuracy of manual diagnosis for cervical zygapophysial joint pain syndromes. The Medical Journal of Australia, 148(5), 233-236.

- Jull, G., Barrett, C., Magee, R., & Ho, P. (1999). Further clinical clarification of the muscle dysfunction in cervical headache. Cephalalgia, 19(3), 179-185.

- Watson, D. H., & Trott, P. H. (1993). Cervical headache: an investigation of natural head posture and upper cervical flexor muscle performance. Cephalalgia, 13(4), 272-284.

- Treleaven, J., Jull, G., & Atkinson, L. (1994). Cervical musculoskeletal dysfunction in post‐concussional headache. Cephalalgia, 14(4), 273-279.

- McDonnell, M. K., Sahrmann, S. A., & Van Dillen, L. (2005). A specific exercise program and modification of postural alignment for treatment of cervicogenic headache: a case report. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 35(1), 3-15.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. (1988). Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Cephalalgia, 8(7), 1-96.

- Travell JG, Simons DG. (1983) The upper extremities. In Myofascial pain and dysfunction: The trigger point manual. Volume 1: Williams & Wilkins,pp 165-330.

- Roth, J. K., Roth, R. S., Weintraub, J. R., & Simons, D. G. (2007). Cervicogenic headache caused by myofascial trigger points in the sternocleidomastoid: a case report. Cephalalgia, 27(4), 375-380.

- Goodman, C., & Fuller, K. (2009). Pathology Implications for the Physical Therapist (3rdedn) St. Louis: Saunders, 2009, 625-626.

- Bovim, G. (1992). Cervicogenic headache, migraine, and tension-type headache. Pressure-pain threshold measurements. Pain, 51(2), 169-173.

- Fritz, J. M., & Brennan, G. P. (2007). Preliminary examination of a proposed treatment-based classification system for patients receiving physical therapy interventions for neck pain. Physical therapy, 87(5), 513-524.

- Luedtke, K., Allers, A., Schulte, L. H., & May, A. (2016). Efficacy of interventions used by physiotherapists for patients with headache and migraine—systematic review and meta-analysis. Cephalalgia, 36(5), 474-492.

- Zito, G., Jull, G., & Story, I. (2006). Clinical tests of musculoskeletal dysfunction in the diagnosis of cervicogenic headache. Manual therapy, 11(2), 118-129.

- Jull, G. A., & Stanton, W. R. (2005). Predictors of responsiveness to physiotherapy management of cervicogenic headache. Cephalalgia, 25(2), 101-108.

- Bodes-Pardo, G., Pecos-Martín, D., Gallego-Izquierdo, T., Salom-Moreno, J., Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C., & Ortega-Santiago, R. (2013). Manual treatment for cervicogenic headache and active trigger point in the sternocleidomastoid muscle: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics, 36(7), 403-411.

- Jull, G., Amiri, M., Bullock-Saxton, J., Darnell, R., & Lander, C. (2007). Cervical musculoskeletal impairment in frequent intermittent headache. Part 1: Subjects with single headaches. Cephalalgia, 27(7), 793-802.

- Zito, G., Jull, G., & Story, I. (2006). Clinical tests of musculoskeletal dysfunction in the diagnosis of cervicogenic headache. Manual therapy, 11(2), 118-129.

- Jull, G., Barrett, C., Magee, R., & Ho, P. (1999). Further clinical clarification of the muscle dysfunction in cervical headache. Cephalalgia, 19(3), 179-185.

- Watson, D. H., & Trott, P. H. (1993). Cervical headache: an investigation of natural head posture and upper cervical flexor muscle performance. Cephalalgia, 13(4), 272-284.

- Jull, G., & Niere, K. (2004). The cervical spine and headache.

- Treleaven, J. (2008). Sensorimotor disturbances in neck disorders affecting postural stability, head and eye movement control. Manual therapy, 13(1), 2-11.

- Reid, S. A., Rivett, D. A., Katekar, M. G., & Callister, R. (2008). Sustained natural apophyseal glides (SNAGs) are an effective treatment for cervicogenic dizziness. Manual therapy, 13(4), 357-366.

- Bansevicius, D., & Sjaastad, O. (1996). Cervicogenic headache: the influence of mental load on pain level and EMG of shoulder‐neck and facial muscles. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 36(6), 372-378.

- Jull, G., Barrett, C., Magee, R., & Ho, P. (1999). Further clinical clarification of the muscle dysfunction in cervical headache. Cephalalgia, 19(3), 179-185.

- Watson, D. H., & Trott, P. H. (1993). Cervical headache: an investigation of natural head posture and upper cervical flexor muscle performance. Cephalalgia, 13(4), 272-284.

- Jull, G., Amiri, M., Bullock-Saxton, J., Darnell, R., & Lander, C. (2007). Cervical musculoskeletal impairment in frequent intermittent headache. Part 1: Subjects with single headaches. Cephalalgia, 27(7), 793-802.

- Olson, V. L. (1997). Whiplash-associated chronic headache treated with home cervical traction. Physical therapy, 77(4), 417-424.

- Jull, G., Trott, P., Potter, H., Zito, G., Niere, K., Shirley, D., … & Richardson, C. (2002). A randomized controlled trial of exercise and manipulative therapy for cervicogenic headache. Spine, 27(17), 1835-1843.

- Page, P. (2011). Cervicogenic headaches: an evidence-led approach to clinical management. International journal of sports physical therapy, 6(3), 254.

- Jull, G., Trott, P., Potter, H., Zito, G., Niere, K., Shirley, D., … & Richardson, C. (2002). A randomized controlled trial of exercise and manipulative therapy for cervicogenic headache. Spine, 27(17), 1835-1843.

- Jull, G., Trott, P., Potter, H., Zito, G., Niere, K., Shirley, D., … & Richardson, C. (2002). A randomized controlled trial of exercise and manipulative therapy for cervicogenic headache. Spine, 27(17), 1835-1843.

- Bogduk, N., & Govind, J. (2009). Cervicogenic headache: an assessment of the evidence on clinical diagnosis, invasive tests, and treatment. The Lancet Neurology, 8(10), 959-968.

- Bajwa, Z. H., & Watson, J. C. (2016). Cervicogenic headache. Last updated May, 2018.

- Bogduk, N., & Govind, J. (2009). Cervicogenic headache: an assessment of the evidence on clinical diagnosis, invasive tests, and treatment. The Lancet Neurology, 8(10), 959-968.

- Anthony, M. (2000). Cervicogenic headache: prevalence and response to local steroid therapy. Clinical and experimental Rheumatology, 18(2; SUPP/19), S-59.

- Lord, S. M., Barnsley, L., Wallis, B. J., & Bogduk, N. (1994). Third occipital nerve headache: a prevalence study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 57(10), 1187-1190.

- Lord, S. M., Barnsley, L., Wallis, B. J., & Bogduk, N. (1996). Chronic cervical zygapophysial joint pain after whiplash: a placebo-controlled prevalence study. Spine, 21(15), 1737-1744.

- Jull, G. (1985). Manual diagnosis of C2-3 headache. Cephalalgia, 5(3_suppl), 308-309.

- Slipman, C. W., Lipetz, J. S., Plastaras, C. T., Jackson, H. B., Yang, S. T., & Meyer, A. M. (2001). Therapeutic zygapophyseal joint injections for headaches emanating from the C2-3 joint. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation, 80(3), 182-188.

- Bogduk, N., & Govind, J. (2009). Cervicogenic headache: an assessment of the evidence on clinical diagnosis, invasive tests, and treatment. The Lancet Neurology, 8(10), 959-968.

- Govind, J., King, W., Bailey, B., & Bogduk, N. (2003). Radiofrequency neurotomy for the treatment of third occipital headache. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 74(1), 88-93.

- Barnsley, L. (2005). Percutaneous radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic neck pain: outcomes in a series of consecutive patients. Pain Medicine, 6(4), 282-286.

- Lord, S. M., Barnsley, L., Wallis, B. J., McDonald, G. J., & Bogduk, N. (1996). Percutaneous radio-frequency neurotomy for chronic cervical zygapophyseal-joint pain. New England Journal of Medicine, 335(23), 1721-1726.

- Bajwa, Z. H., & Watson, J. C. (2016). Cervicogenic headache. Last updated May, 2018.

- Barendse, G. A., Sluijter, M. E., Sjaastad, O., & Weber, W. E. (1998). Radiofrequency cervical zygapophyseal joint neurotomy for cervicogenic headache: a prospective study of 15 patients. Functional neurology, 13(4), 297-303.

- Stovner, L. J., Kolstad, F., & Helde, G. (2004). Radiofrequency denervation of facet joints C2‐C6 in cervicogenic headache: A randomized, double‐blind, sham‐controlled study. Cephalalgia, 24(10), 821-830.

- Haspeslagh, S. R., Van Suijlekom, H. A., Lamé, I. E., Kessels, A. G., van Kleef, M., & Weber, W. E. (2006). Randomised controlled trial of cervical radiofrequency lesions as a treatment for cervicogenic headache. BMC anesthesiology, 6(1), 1.

- Asopa, A. (2015). Systematic review of radiofrequency ablation and pulsed radiofrequency for management of cervicogenic headache. Pain physician, 18, 109-130.

- Elsocht, G., Delaunaij, T., Van Durme, M., & Van Hautegem, E. Cervicogenic Headache.

- Slipman, C. W., Lipetz, J. S., Plastaras, C. T., Jackson, H. B., Yang, S. T., & Meyer, A. M. (2001). Therapeutic zygapophyseal joint injections for headaches emanating from the C2-3 joint. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation, 80(3), 182-188.

- Narouze, S. N., Casanova, J., & Mekhail, N. (2007). The longitudinal effectiveness of lateral atlantoaxial intra-articular steroid injection in the treatment of cervicogenic headache. Pain medicine, 8(2), 184-188.

- Martelletti, P., Di Sabato, F., Granata, M., Alampi, D., Apponi, F., Borgonuovo, P., … & Giacovazzo, M. (1998). Epidural corticosteroid blockade in cervicogenic headache. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences, 2, 31-36.

- Reale, C., Turkiewicz, A. M., Reale, C. A., Stabile, S., Borgonuovo, P., & Apponi, F. (2000). Epidural steroids as a pharmacological approach. Clinical and experimental rheumatology, 18(2; SUPP/19), S-65.

- Martelletti, P., Di Sabato, F., Granata, M., Alampi, D., Apponi, F., Borgonuovo, P., … & Giacovazzo, M. (1998). Failure of long-term results of epidural steroid injection in cervicogenic headache. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences, 2(1), 10.

- Slipman, C. W., Lipetz, J. S., Plastaras, C. T., Jackson, H. B., Yang, S. T., & Meyer, A. M. (2001). Therapeutic zygapophyseal joint injections for headaches emanating from the C2-3 joint. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation, 80(3), 182-188.

- Joseph, B., & Kumar, B. (1994). Gallie’s fusion for atlantoaxial arthrosis with occipital neuralgia. Spine, 19(4), 454-455.

- Ghanayem, A. J., Leventhal, M., & Bohlman, H. H. (1996). Osteoarthrosis of the Atlanto-axial Joints.: Long-term Follow-up after Treatment with Arthrodesis. JBJS, 78(9), 1300-1307.

- Schaeren, S., & Jeanneret, B. (2005). Atlantoaxial osteoarthritis: case series and review of the literature. European Spine Journal, 14(5), 501-506.

- Pikus, H. J., & Phillips, J. M. (1995). Characteristics of patients successfully treated for cervicogenic headache by surgical decompression of the second cervical root. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 35(10), 621-629.

- Joseph, B., & Kumar, B. (1994). Gallie’s fusion for atlantoaxial arthrosis with occipital neuralgia. Spine, 19(4), 454-455.

- Ghanayem, A. J., Leventhal, M., & Bohlman, H. H. (1996). Osteoarthrosis of the Atlanto-axial Joints.: Long-term Follow-up after Treatment with Arthrodesis. JBJS, 78(9), 1300-1307.

- Schaeren, S., & Jeanneret, B. (2005). Atlantoaxial osteoarthritis: case series and review of the literature. European Spine Journal, 14(5), 501-506.

- Park, S. W., Park, Y. S., Nam, T. K., & Cho, T. G. (2011). The effect of radiofrequency neurotomy of lower cervical medial branches on cervicogenic headache. Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society, 50(6), 507.

- Antonaci, F., & Sjaastad, O. (2011). Cervicogenic headache: a real headache. Current neurology and neuroscience reports, 11(2), 149-155.

- Bajwa, Z. H., & Watson, J. C. (2016). Cervicogenic headache. Last updated May, 2018.